First published in 1905 by Frank Cass and Company Limited

This edition first published in 2018 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1905 Albert Frederick Pollard

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and welcomes correspondence from those they have been unable to contact.

A Library of Congress record exists under ISBN:

ISBN 13: 978-0-367-15018-1 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-0-429-05452-5 (ebk)

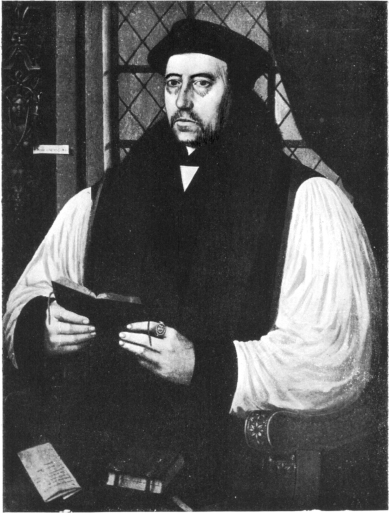

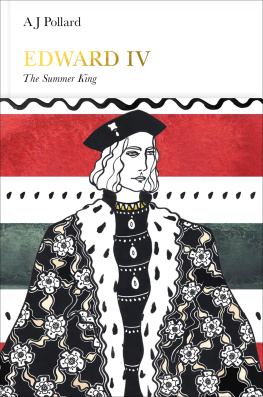

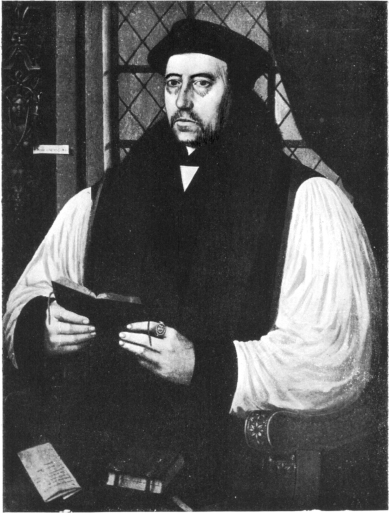

THOMAS CRANMER

Copyright Photo., Walker & CockerelL

THOMAS CRANMER,

ARCHBISHOP OF CANTERBURY.

PAINTER, G. FLICCIUS.

PREFACE

I F an author might frankly review his own book in his Preface, the following pages would take as their text the caution, Beware of too much explaining lest we end by too much excusing. For the present volume seeks to explain as much as possible. To extenuate nothing is a golden rule, but the grossest injustice ensues upon a neglect of extenuating circumstances. All the proverbs notwithstanding, explanation is the first duty of the historian and the biographer; and Cranmer has been termed the most mysterious figure in the English Reformation. The obscurity is not in his character, but in the atmosphere which he breathed, and atmosphere is the most difficult of all things to re-create. As a rule there are no materials; for to people who live in it, a political or religious atmosphere is a familiar thing, which needs no explanation and therefore is not recorded in documents. Then the atmosphere changes, and can only be recalled to posterity by an observation and reflexion compared with which the mere ascertainment of facts is easy.

A failure to realise this unfamiliar atmosphere vitiates most of the estimates of Cranmers career and character, and notably those of the Whig school represented by Hallam and Macaulay. Hallam indeed always recognises that Cranmers faults were the effect of circumstances and not of intention, but he blames the Archbishop for having consented to place himself in a station where those circumstances occurred. He might perhaps have made the great refusal; but unless some one had been willing to take up the burden with all its irksome conditions, there would have been no Reformation. And in one like Cranmer, who for years had been praying for the abolition of the Popes power in England, it surely would have been a cowardly love of mental and physical ease to decline his share in the work because of the sacrifice it involved. He chose the better part, but it was one of labours and sorrows. To succeed Warham who had just surrendered the keys of ecclesiastical independence; to be Archbishop under Henry VIII. who had broken the powerful Wolsey without an effort; then, after two years comparative peace with Somerset, to be flouted for four by Northumberland; and finally, under Mary, to hold views of the State which compelled non-resistance, and yet to have a conscience which said that submission was cowardice such was Cranmers lot. Compared with Henry VIII. he is weak, but none the less human for that. He is the storm-tossed plaything of forces which even Henry could not completely control; and his soul is expressed in the beautiful and plaintive strains of his Litany, which appealed to mens hearts in those troublous times with a directness now scarcely conceivable. His story is that of a conscience in the grip of a stronger power; but, unless I misread his mind, he surveyed his lifes work in the hour of death and was satisfied.

It has been maintained by an eminent scholar recently dead that the chief content of modern history is the emancipation of conscience from the control of authority. From that point of view the student of Tudor times will not be exclusive in his choice of heroes. He will find room in his calendar of saints for More as well as for Cranmer. Both had grave imperfections, and both took their share in enforcing the claims of authority over those of conscience. Nor perhaps is it true to say that they died in order that we might be free; but they died for conscience sake, and unless they and others had died conscience would still be in chains. That was Cranmers service in the cause of humanity; his Church owes him no less, for in the Book of Common Prayer he gave it the most effective of all its possessions.

The materials for sixteenth-century history are so vast that no one can hope to master them all in the allotted span of human life published by the Record Office under the editorship of the late Mr. Brewer and Dr. James Gairdner, which so far as it goes (1544) completely supersedes all other sources for Cranmers life. Another recently published authority of the highest value is the Acts of the Privy Council, extending from 1542 to 1599; but the domestic State Papers from 1547 onwards are poorly represented in Lemons Calendar (1860); and although the correspondence of English agents abroad is more adequately summarised in Turnbulls Foreign Calendar, the more valuable despatches of foreign ambassadors in England are yet unpublished with the exception of two volumes issued by the French Government, Browns Venetian Calendar, and the Spanish Calendar, which has not yet touched the reign of Edward VI. or Mary. The great collections in the British Museum are also for the most part unprinted.

Of contemporary chronicles, Halls is the best for the reign of Henry VIII., and for that of Edward VI. the most useful authority is J. G. Nicholss Literary Remains of Edward VI. (Roxburghe Club, 1857, 2 vols.), which is perhaps more important for the numerous contemporary documents it prints than for the young Kings Journal, which is its pice de resistance. Of the many valuable chronicles published by the Camden Society may be mentioned Wriothesleys Chronicle, the Greyfriars Chronicle, the Chronicle of Queen Jane and Queen Mary, Mach-yns Diary, and the Narratives of the Reformation.

With regard to church history, the primary source is the works of the Reformers themselves; they are here cited in the Parker Societys collected edition in fifty-four volumes (Cambridge, 184155). This includes the latest edition of Cranmers own works (2 vols., 184446), The latest history of the Reformation on an ambitious scale is that of Canon Dixon (6 vols., 187899), a work of great labour, but perhaps a criticism rather than a history of the Reformation. The best summary of the facts is given in Dr. Gairdners volume (1902) in Stephens and Hunts