The University Press of Mississippi is the scholarly publishing agency of the Mississippi Institutions of Higher Learning: Alcorn State University, Delta State University, Jackson State University, Mississippi State University, Mississippi University for Women, Mississippi Valley State University, University of Mississippi, and University of Southern Mississippi.

www.upress.state.ms.us

The University Press of Mississippi is a member of the Association of University Presses.

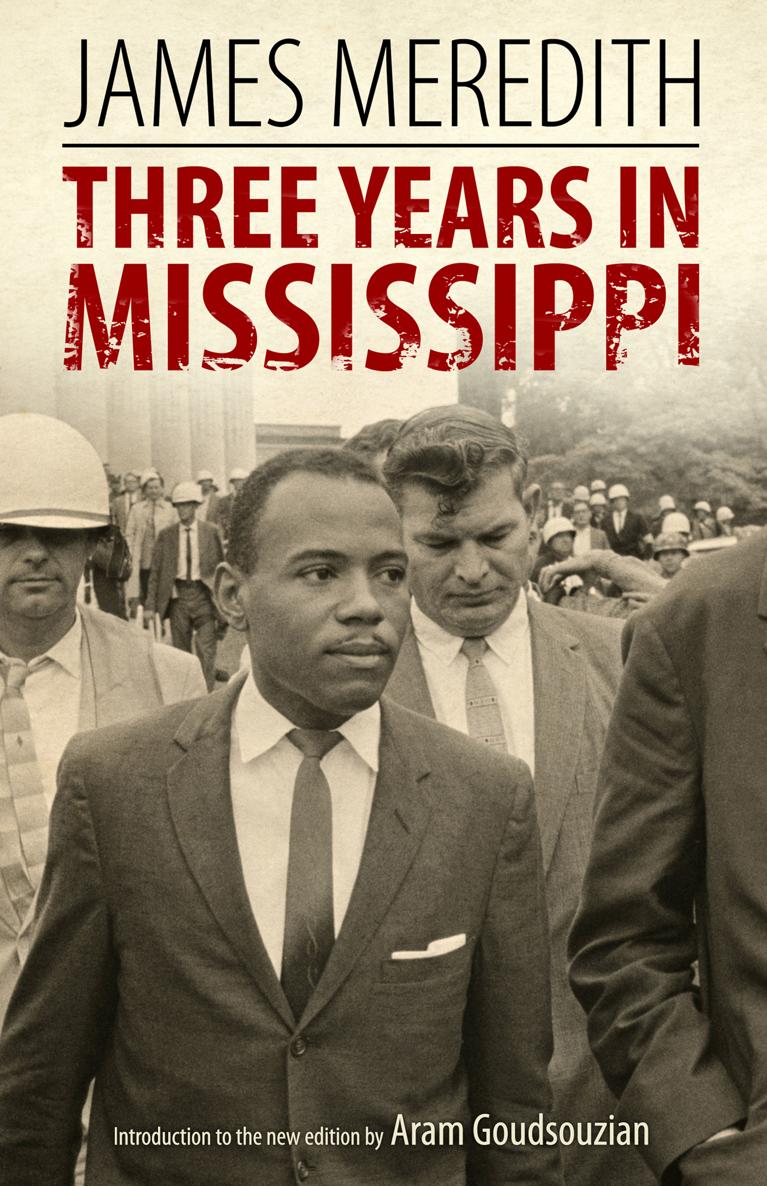

Copyright 1966 by James Meredith

Introduction to the new edition 2019 by Aram Goudsouzian

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

UPM first printing 2019

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Meredith, James, 1933 author. | Goudsouzian, Aram, author of introduction.

Title: Three years in Mississippi / James Meredith, introduction to the new edition by Aram Goudsouzian.

Other titles: Civil rights in Mississippi.

Description: Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, [2019] | Series: Civil rights in Mississippi | Introduction to the new edition 2019 by Aram Goudsouzian. | UPM first printing 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018049604| ISBN 9781496821010 (cloth) | ISBN 9781496821065 (pbk.) | ISBN 9781496821034 (epub institutional) | ISBN 9781496821027 (epub single) | ISBN 9781496821041 (pdf single) | ISBN 9781496821058 (pdf institutional)

Subjects: LCSH: Meredith, James, 1933 | University of MississippiHistory. | African American college studentsMississippiBiography. | African AmericansCivil rights. | Civil rightsMississippi. | MississippiSocial conditions.

Classification: LCC LD3412.9 .M477 2019 | DDC 378.762/83dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018049604

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

INTRODUCTION TO THE NEW EDITION

Aram Goudsouzian, 2017

If you ever find yourself at the University of Mississippi, also known as Ole Miss, take a stroll through the grassy, tree-dotted expanse leading into the heart of campus, known as the Grove. As you reach the Circle, look up. Behold a heroic statue of a Confederate soldiera memorial of Southern sacrifice, a romantic symbol of honor, manhood, and whiteness. (A modern marker at its base reminds you that it was erected in 1906, promoting a Lost Cause mentality that erased the role of slavery in the Civil War). Keep walking under the shade of stately elms, oaks, and magnolias, with lush grass and delicate pansies along your path. Pass the American flag at the center of the Circle.

Before you stands the Lyceum, a majestic red-brick edifice framed by white columns dating back to the universitys founding in 1848. Another historic marker informs you that the Lyceum was the scene of a major event in the Civil Rights Movement. In 1962, thousands of white supremacists had gathered here in a violent siege upon US marshals, who were enforcing the racial integration of Ole Miss. The rioting resulted in the deaths of two innocent men. It illustrated the depths of white resistance to black citizenship, staining the reputation of the university and the state.

Now steer a little left. Behind the Lyceum, in an ellipse, is a statue of James Meredith. On the ground lies a small plaque, which describes him as a major figure in the American civil rights movement who opened the doors to higher education at the University of Mississippi. The statue, somewhat larger than the man himself, appears to be striding forward. If you follow that path for fifteen feet into a four-column monument ringed by a short brick wall, you can read quotes on the walls from former governor William Winter, civil rights activist Myrlie Evers-Williams, and Ole Miss chancellor Robert Khayat. The fourth quote is from James Merediths 1966 memoir, Three Years in Mississippi. It states:

Always, without fail, regardless of the number of times I enter Mississippi, it creates within me feelings that are felt at no other time joy hope love. I have always felt that Mississippi belonged to me and one must love what is his.

James Meredith, through his singular will and courage, forced crises that eroded the foundation of Jim Crow. But the statue at the University of Mississippi sidesteps his true historical legacy. Then again, Meredith evades description. He is a paradox: arguably the most significant figure in Mississippis civil rights movement, he stands almost entirely apart from it. In the midst of a collective movement for social justice, Meredith battled as an individual. He is an iconoclast, resistant to any label, at once calculated and erratic. What drove his audacious actions? What did they mean? The clues lie in his words.

My father was the first member of his family ever to own a piece of land, writes Meredith. In his house I learned the true meaning of life. Here I learned that death was to be preferred to indignity. Those lines capture some of his core values. He considered his father a model of manhood. He cherished land as a means of independence. And he displayed extraordinary courage while demanding his due respect.

J. H. Meredith was born on June 25, 1933, in Kosciusko, the seat of Attala County, located in the rural Hill Country of central Mississippi. His parents, Moses Cap Meredith and Roxie Marie Patterson Meredith, instilled values of responsibility, discipline, education, and pride. They had little, but they worked hard and saved money. All ten of their children finished high school and many attended college. When not at school, their children stayed on the farm, insulated from Jim Crow society. J, as he was known, was smart and driven. For his senior year of high school, he lived with an uncle in St. Petersburg, Florida. Then he enrolled in the Air Force under the name James Howard Meredith.

Meredith spent most of the 1950s in the Air Force. Stationed at bases around the country, he received good evaluations and earned promotion to sergeant. He took college courses at various institutions, married his wife June, and saved enough money to buy 141 acres in his native Attala County. In 1957 the Air Force transferred him to Tachikawa AFB, outside Tokyo, Japan. On the one hand, the experience was liberating, as he escaped the racial prejudices of

Three Years in Mississippi opens with Merediths return to his home state in August 1960, after a decade away. He meshes the perspectives of a native son and a foreign correspondent. In some of the books most affecting insights, he describes his mixed emotions about the Magnolia State, his strategies for preserving dignity amidst a repressive system, the geography and culture of Kosciusko, and the hypocrisies of white authorities. He adeptly chronicles black life in Mississippi, including its rituals and characters, its class differences and color gradations, its low-down entertainments and spiritual heights. He also gives indications of his unique personality and ideology. He writes: My most stabilizing belief is that I never have made a mistake in my life, because I never make arbitrary or predetermined decisions. That might sound grandiose, but he believed that he possessed a special destiny, a divine responsibility.