IDITAROD

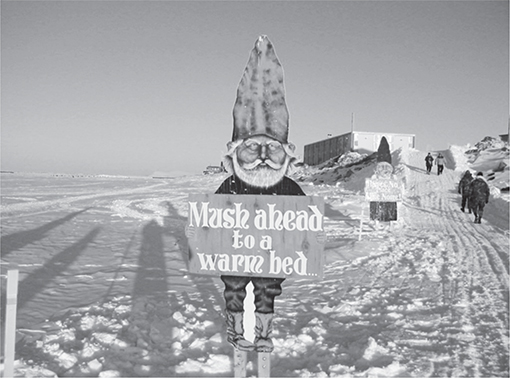

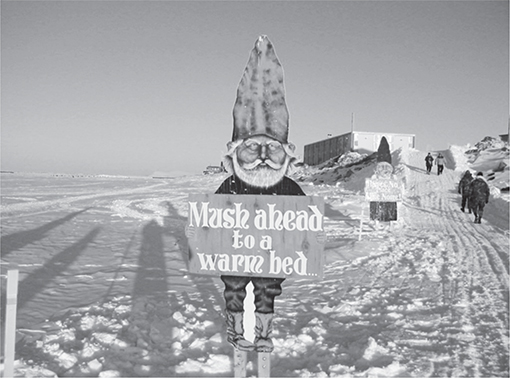

During the 2003 race, a series of gnomes were on hand to greet, encourage, and direct mushers. The messages were erected on the sea ice near the ramp that sends mushers up to Nomes Front Street. A few blocks farther along, they pass beneath the Burled Arch. (Barbara Lake.)

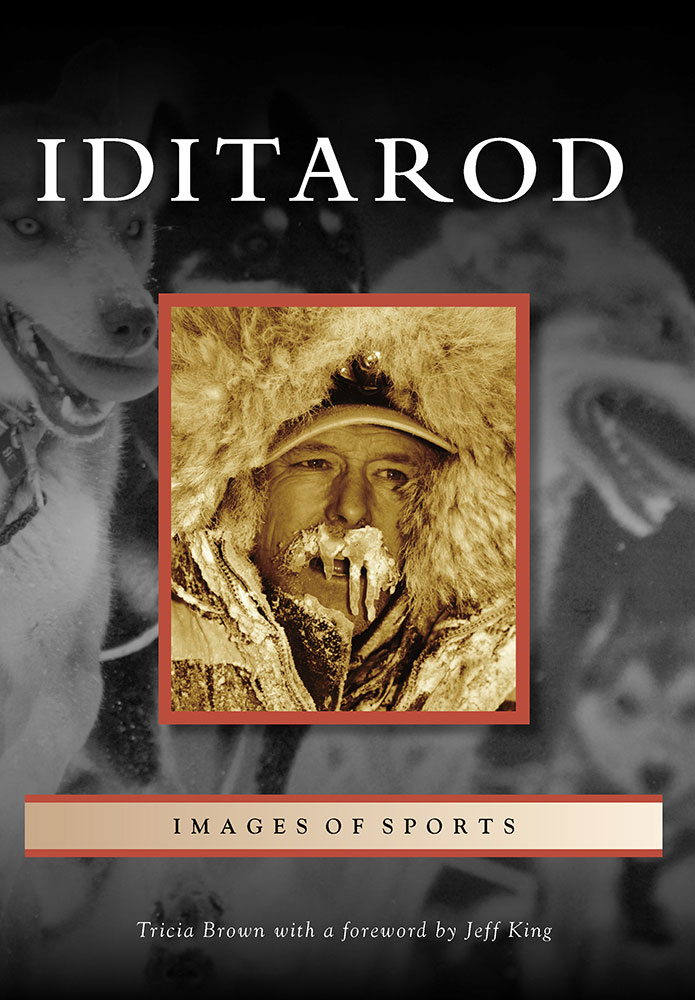

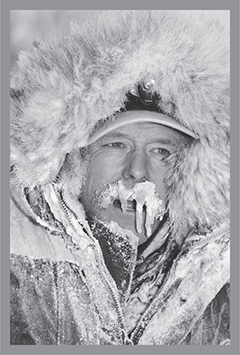

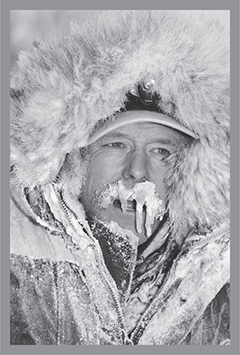

ON THE FRONT COVER: Repeat champion Jeff King is pictured at the Takotna checkpoint in 2006 as he was on his way to his fourth Iditarod win. Heavy breathing while running in below-zero temperatures can create ice on a mushers facial hair. (Jeff Schultz.)

COVER BACKGROUND: An eager team leaves the start line in Willow during the 2010 Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race. (Frank Kovalchek.)

ON THE BACK COVER: After weeks of travel, the first dog team arrived in Seward from Nome on what was then called the Seward Trail. A party of five men traveling by dog team surveyed the route for the Alaska Road Commission (ARC) in the winter of 1908. Subsequently, the ARC spent $10,000 developing the route, which soon became widely known as the Iditarod Trail. (Library of Congress; photograph by S. Sexton.)

IDITAROD

Tricia Brown

with a foreword by Jeff King

Copyright 2014 by Tricia Brown

ISBN 978-1-4671-3104-9

Ebook ISBN 9781439642375

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013956054

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

Iditarod, Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race, Last Great Race, The Last Great Race on Earth and Iditarod Trail Committee are registered trademarks of the Iditarod Trail Committee, Inc.

To all you Iditarod peoplethe mushers and their families, handlers, race volunteers, administrators, and fanswho know life is not complete unless it is shared with sled dogs.

CONTENTS

Alone with my dogs in the remote wilderness just north of Mount McKinley, I struggled to make sense of the scratchy AM radio reports of a sled dog race going on between Anchorage and Nome. How was it even possible? And who were the people doing this amazing thing?

The why was easier to figure out. I could imagine how it must feel to spend weeks with your dogs while crossing the expanses of this great state. Even then, I was living out a childhood dream: traveling by dog team, living in a tent, and running a trapline in one of the most remote and beautiful places I could ever imagine. It made me feel small, and I yearned to find out more about the people, the dogs, and the history behind the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race.

I was a young, twentysomething musher the first time I laid eyes on Joe Redington Sr., known as the Father of the Iditarod, but the experience is still as clear today as it was that summer of 1980. I saw before me a short, pleasant individual who exuded an energy and spirit that no one could mistake for anything but confidence and tenacity. I found myself challenged to keep up with him as he ran up the rickety stairs in the back of Teelands Country Store in Wasilla. I followed him into what was then the Iditarod headquarters above a dry goods, hardware, and tobacco shop. I was ready to do this thing.

By the winter of 1979, I had been in a few dog races, including the Gold Miners 140 from Nenana to Manley, where I raced against Iditarod champion Jerry Riley. There, I also met Joe Redingtons son Joee, and his son. Joee was an accomplished sprint racer and had completed the Iditarod as well. As I sat around the parlor stove with the Redingtons in Manley, Joee lamented how hard it was to keep up with his dads accomplishments. He explained to me how Joe Sr. had just summited Mount McKinley with a dog team and a young woman named Susan. I would later learn that she was the up-and-comer Susan Butcher, who went on to claim four Iditarod championships in her career.

How can I ever top that? he asked. I guess Ill have to swim the English Channel with my dog team and an 18 year old. Still, Joees gruff account of his fathers endeavors did not hide the pride he had for his dad.

After leaving Settlers Bay on the first Saturday in March 1981, I headed to Nome in my wool pants and wool shirtthe warmest clothes of the timeand had packed a good ol Coleman cookstove in my sled (makes me wonder what that packed sled weighed in comparison to my sled this year). When the countdown was finished and my team blasted from the start line, I was struck by the reality of 1,000 miles of trail in front of me. Had there not been teams ahead of and behind me, I would have said it could not be done. The mantra four on, four offthe alternating hours of run and rest timewas ringing in my ears as 13 of the 14 dogs I owned were out in front of me, charging up the trail.

Who were the people who had dreamed this up? And how was it that they had allowed me to join them? Rick, Jerry, and Herbie; Sonny, Susan, and Libby; Emmitt, Ken, and Gerald: the list has grown over the years to include incredible individuals with a combined set of cunning, grit, and perseverance that was unmatched by any group I have ever met.

Like a revolving door, my first race wore on. As I grew drunk with fatigue, it was hard to tell dream from reality. The flicker of a headlamp or the twinkle of a star? Village lights or a campfire in the distance? They twinkled and were gone. Dream or reality? I could not be sure. Chills from the arctic cold seeped through faulty zippers. Thirst burned and the water bottle froze. The dogs trotted on. Where were the other teams? Who was ahead? How far to the checkpoint? Did we miss a turn in the trail? The dogs trotted on.

Then, unmistakably, the lights of the village and the smell of wood smoke confirmed our arrival. The dogs picked up their pace. The lure of a warm spot to lie down, dry socks, and hot Tang pushed us on.

The sensory memory is still vivid for me, even though the experience took place more than three decades ago. And were still coming back.

The lure of the Iditarod Trail runs deep. The trail makes us feel whole. The dogs make us feel loved. The adventure nourishes our soul.

Jeff King

Denali Park, Alaska

Iditarod Champion1993, 1996, 1998, and 2006

Our warm thanks go to the Iditarod Trail Committee, Inc. (ITC); Stan Hooley; Joanne Potts; Diane Johnson; Jeff Schultz; Jeff King; Lance Mackey; Dick Mackey; Dan Seavey; Vern Halter; Ramey Smyth and Becca Moore; Chuck and Shirley Newberg; Rose Albert; Ellen Donoghue; Gale Van Diest; Jon Van Zyle; Frank Kovalchek; Kjersti M.G. Mjrum; Barbara Lake; KYUK-FM; Theresa Daily; Libbie Martin; and Clark Fair. Special thanks to Jeff Ruetsche, Sara Miller, and the team at Arcadia Publishing.

Many of the early-20th-century images in this volume are now in the public domain courtesy of the Frank and Frances Carpenter Collection, a 1951 gift to the Library of Congress (LC) by Frances Carpenter, who donated the collection under her married name, Mrs. W. Chapin Huntington. Unless otherwise noted, all images are courtesy of the author.

Next page