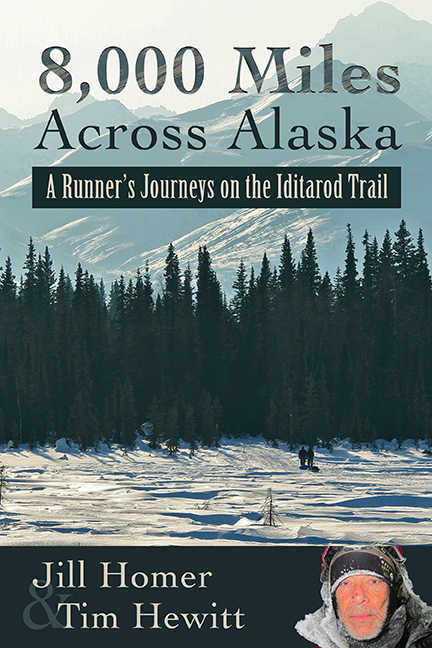

8,000 Miles Across Alaska

A Runners Journeys on the Iditarod Trail

By Jill Homer

Contributions from notes by Tim Hewitt

Edited by Diana Miller

Smashwords edition

Distributed by Arctic Glass Press,

www.arcticglasspress.com

Cover: Tim and Loreen Hewitt approach the Alaska Range during the 2011 Iditarod Trail Invitational. Photo by Mike Curiak.

This is a work of narrative nonfiction. Dialogue and events herein have been recounted to the best of the subjects memory.

Introduction

Beyond the very extreme of fatigue and distress, we may find amounts of ease and power we never dreamed ourselves to own, sources of strength never taxed at all because we never push through the obstruction.

~William James, philosopher

F ew moments will make a person feel more alone than stopping at random in a snow-covered wilderness to sleep. And yet, few moments will make one feel more alive than waking up in that wilderness to pink sunlight and piercing cold, wholly independent in a beautiful and terrifying world.

For Tim Hewitt, dozens of these moments consolidate in memories, infusing a typically hectic life with quiet refrain. The sky opens up in penetrating darkness, with a clarity that pulls the curtain from unknowable depths of the universe. Stars shimmer like spotlights behind a ballet of Northern Lights, as green waves of aurora glide above the horizon. The boreal forest stands in rapt attention, with clusters of spruce trees leaning away from the prevailing wind, giving the appearance that they, too, are gazing up at the sky. This is where Tim spreads out his sleeping bag in a bed of clean snow, beside the protection of trees, and away from the tracks of territorial moose. On calm and cold nights, ice crystals jingle in the air like tiny bells. More often than not, sleep battles a clamorous wind that roars through this symphony of solitude.

Exhaustion has a way of amplifying isolation and vice versa, and walking a thousand miles across Alaska can rattle a person to pieces. A shattered body sometimes revolts against its tyrannical mind, and there were nights when Tim nearly lost lifes most crucial battles. At its worst, sleep just forced its way in as though his body suddenly went on strike even when his conscience screamed to keep moving.

There was one such night on the jumbled ice of Golovin Bay, a small pocket of the Bering Sea just a hundred miles from Nome. A fierce storm charged through the night, a blitzkrieg of hurricane-force winds that pushed a jet stream of snow across the white expanse. Tim battled the blizzard to the edge of a pressure ridge a broken wall of ice slabs lifted by ocean currents like concrete after an earthquake. Blowing snow streamed over the slabs and Tim could see, on the leeward side, a depression with clear air the tiniest sliver of protection. Against all remaining logic, Tim unhooked from his sled and spread out his sleeping bag against the eighteen-inch barrier hardly higher than his reclined body. His movements were emotionless and mechanical, as though he was observing his body act independently of his mind while he surrendered in the bowels of a subzero cyclone. As wind continued to pummel the sleeping bag, his body soon began to thrash with shivering convulsions. It was impossibly cold, with wind chill approaching 100 below zero.

In these conditions, the only orders that make any sense are do not stop. Yet Tim felt helpless against a desperate fatigue. He wasnt certain that he could physically take another step into the storm, and yet he was certain that he wouldnt survive if he stayed. The wind chill and exhaustion drained heat from his body, leaving skin icy and extremities numb. It felt like dying, and yet some base instinct still demanded rest against the odds of survival. Tims thoughts echoed through the hollow chamber where his body held them hostage: If you fall asleep, you will never wake up.

His mind conjured up images of a corpse frozen inside an ice-encrusted sleeping bag, wedged where the wind had driven it between slabs of ice. If he was lucky, Alaska Natives would find his body before spring came and the Bering Sea swallowed what was left. He imagined a group standing over his rigid remains, speculating at the circumstances that would cause a man to end up alone on the sea ice without a snowmobile or even sled dogs.

Mustve gotten lost in the storm, one would say.

Sure, another would reply. But what was he doing out in that blizzard?

Even Tim had a difficult time answering this question why did he run and walk and trudge a thousand miles across Alaska on the Iditarod Trail? Because its there wasnt adequate. As a challenge or for the adventure of it were closer, but still too vague. The thousand-mile dog sled race on the Iditarod Trail is often called The Last Great Race but theres another, much more obscure race, where participants dont even have the help of dogs. Formerly called the Iditasport and now the Iditarod Trail Invitational, this race challenges cyclists, skiers, and runners to complete the distance under their own power and without much in the way of outside support. Its more of an expedition than a race, and Tim Hewitt is the only person to have completed it more than three times. His actual number? An astonishing eight. Six of those, he won or tied.

But no one who sees Tim on the street near his law firm in Pittsburgh would ever suspect that battling hurricane-force blizzards is something he does in his spare time. Fifty-nine years old with a slim build, a bright smile, and cropped gray hair, Tim isnt the stereotype of a grizzled Arctic explorer. Hes an employment lawyer, a talented amateur runner, a father to four daughters, and a husband to an equally adventurous wife. But his well-kept home on a lake outside Pittsburgh harbors subtle evidence of another life: an Iditarod Trail marker attached to the mail box, a photograph of the white-capped mountains surrounding Rainy Pass, and a few screen-printed T-shirts and hats that were the only tangible prizes for participation in the race beyond The Last Great Race.

These objects serve as mementos of a truly unique accomplishment. Far more people have reached the summit of Mount Everest than Nome under their own power, and its incredibly unlikely that another person will ever try for eight (or more Tim hasnt shown any inclination toward stopping just yet).

Why? remains a valid question. The Iditarod Trail Invitational is a race that has no prize money, no spectators cheering at the finish, no awards, no trophies. There are no logical reasons to participate in such a race, and so participants must find motivation from within. Tim thrives amid adversity, remains cool-headed in the face of great dangers, and relishes in testing his already expansive limits. He also enjoys the mental rewards of every small victory: the many times he wanted to quit and didnt, the lessons he learned, the struggles and successes in simply surviving. Out on windswept ice of Golovin Bay, he knew the stakes were as high as they had ever been. If he emerged from this challenge victoriously, the reward would be the most valuable of all his life.

Visualizing the scene of defeat people discovering his corpse frozen against blocks of ice boosted his exhausted and defiant body out of the sleeping bag. The ten-minute stop carried a steep price; his core temperature had dropped substantially, and his motor functions were firing at a fraction of their usual capabilities. Packing up his sled with his back to the wind, he became so wracked with shivering that his arms barely worked. Numb fingers and violent limb convulsions added an urgent impossibility to the simplest chores. Sheer willpower accomplished these tasks, and he turned to face the blizzard with renewed resolve he would get out of this one alive. He always did.