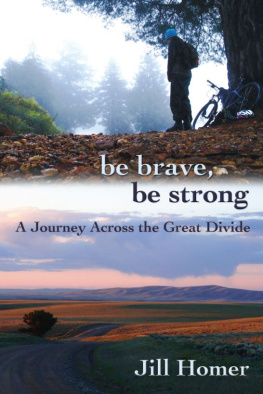

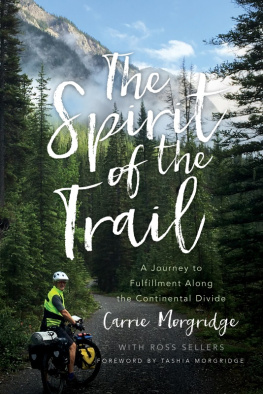

Be Brave, Be Strong

A Journey Across the Great Divide

By Jill Homer

Edited by Diana Miller

Jill Homer

Copyright by Jill Homer 2011

Published by Arctic Glass Press

Smashwords Edition

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form,or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, withoutpermission in writing from the publisher.

Distributed by Arctic Glass Press,www.arcticglasspress.com

Editor: Diana Miller

Cover Design: Jill Homer

Interior Design: Jill Homer

Cover, top: Jill Homer collects herself aftercrashing her mountain bike in the Marin Headlands, California. Selfportrait by Jill Homer.

Cover, bottom: The last tree in a hundred milesstands in Great Divide Basin near Atlantic City, Wyoming. Photo byJill Homer.

This is a work of narrative nonfiction. Dialogue andevents herein have been recounted to the best of the authorsmemory.

Riding the Spine of the Rocky Mountains

Each year on the second Friday inJune, several dozen mountain bikers from around the world set outto challenge speed records on the worlds longest off-pavementcycling route, the Great Divide MountainBike Route. Scouted and mapped by Adventure Cycling Association in1998, the unmarked route features gravel roads, dirt tracks andjeep trails that follow the contours of the ContinentalDivide.

The Great Divide Mountain Bike Route begins inBanff, Alberta, and travels 2,740 miles through the Canadianprovinces of Alberta and British Columbia, and the United States ofMontana, Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, and New Mexico. By the timecyclists reach the Mexican border, they will have climbed nearly200,000 feet over some of the highest and most remote passes in theRocky Mountains.

Endurance legend John Stamstad became thefirst to set a speed record on the Great Divide, blitzing the routein eighteen days and five hours in 1998. In 2004, a handful ofmountain bikers collaborated to challenge that time, organizing aself-supported race on the route beginning at the Montana border.Mike Curiak established a new record at sixteen days. Since then,Great Divide racing has steadily grown and evolved. However, itmaintains the same minimalist format: No entry fee, no coursemarkings and no support. For many distance mountain bikers,completing the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route as fast as possiblehas become the ultimate challenge.

The following is the story of one womans journey todo just that.

Chapter One

Disaster on the Iditarod

Somewhere on a blank slate of tundra, where theshadows of nameless mountains devour the snow, I tried to bury thepieces of myself that I longed to leave behind the pieces thatwere careless, the shards that were weak, and the remnants thatwere terrified of the unknown. Beneath crushing cold and fatigue,they cracked like glass in my cupped mittens. Low-angle sunlightreflected moments from an impossibly distant past my existencebeyond this deep-frozen swamp, before this odyssey that left meboth shattered and enigmatically whole. As a ground blizzard ragedaround my ankles, the wind scattered the pieces like so muchglitter. I watched glimmering reflections of myself swirl throughthe snow until they were invisible, and then gone. I felt like Ihad crossed an irrevocable divide. One I would likely neverapproach again.

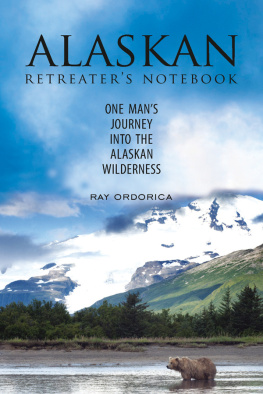

One year passed. The winter sun glared hard andheatless when I lined up for the Iditarod Trail Invitational asecond time. Forty-five runners, skiers and cyclists crowded thestarting line for an adventure race across the frozen wilderness.My boyfriend Geoff, a runner, stood next to me, though my bicyclecreated a barrier between us. A small crowd of spectators gatheredaround the race start, which was little more than a single bannerstretched over the edge of a frozen lake. Anxiety crackled in thecold air. We looked like specks on the tongue of Alaskasbackcountry, staring down its cavernous throat. With only minutesremaining before the start, I contemplated the overwhelming task ofpushing deep into its frigid heart.

I felt like a skydiver in an uncontrolled free fall,watching the wilderness close in around me. I took short, quickbreaths. One for each of the 350 miles in front of me. Secondslanguished on clouds of breath. Geoff coughed and cleared histhroat. A gurgling sound rose from his lungs, broadcasting adeepening infection.

This is going to suck, he said.

Are you feeling any better? I asked, nottaking my eyes off the powder-swept lake.

No, he said. I feel even worse thanyesterday. He coughed again. I struggled to feel sympathy for him.It was a terrible thing, the fact Geoff was sick, but overarchinginstinct told me that traversing 350 miles of Alaska wildernessduring the winter was a bigger battle than either of us should havehad the capacity to fight, healthy or not. And yet, I had finishedthe race before. It took every ounce of energy from my emaciatedbody, but I had finished it one year earlier. For reasons Icouldnt quite explain, even to myself, I needed believe I could doit again. And because we were partners in life, I needed to believeGeoff could do the same.

An informal go rang out and we launched over thestarting line. I rolled my bicycle onto the lake and bogged downalmost immediately. Geoff jogged past as I wrestled the bikethrough the loose snow.

Ill see you at Yentna, I said. Good luck.Geoff nodded and continued ahead.

I watched him fade into the crowd of skiers andrunners as I struggled with the other anchor-weighted cyclists. Iforgot to hug him goodbye, I thought, with selfish disappointmentthat he hadnt bothered to hug me either. Justifiable pre-raceanxiety had strained our final interaction before the start. Butthere was something more, too something more ominous, a thinlyveiled sadness, as though we both suspected certain doom.

I crossed a frozen lake and labored up the firsthill, finally mounting my bike as the snowmobile trail became morepacked at the top. I wove around runners and skiers. I passedGeoff, running steady with his sled attached to a harness, about amile down the trail. With this cruddy trail, youre going to passme again, I said.

Maybe, he replied. I slowed my pedaling andthought about saying goodbye, just in case I didnt see him again,but no words came to my lips.

The last non-cyclist I passed was Pete Basinger, amulti-year veteran and record-holder for the 350-mile race toMcGrath. The human-powered race on the Iditarod Trail had reshapeditself frequently over the years, but Pete remained a constant,lining up for the adventurous if obscure event with his bicycle. Healways finished, and usually won. In 2009, he decided to trysomething different. I approached him as he chopped up a smallincline on a pair of skis, his first venture into the medium.

Pete was the athlete I credited with sparking myotherwise inexplicable desire to enter a race that involves ridinga bicycle over 350 miles of snow during winter in Alaska. Petesendeavors had a way of inspiring passion, simply because heconsistently refused to give up even as situations became sodifficult and ridiculous that they defied all logic andsensibility. Then he would return to race the Iditarod again, eventhough the race did nothing to garner success or even notoriety. Atiny circle of endurance athletes revered him, but to everyoneelse, he was nobody. As Pete toiled year after year throughunrewarded suffering and solitude, his silence spoke volumes abouta deeper meaning behind the race. I listened to his terse reports.I looked at his stark, mostly colorless photographs. Through both,I sensed a power and beauty that I could scarcely comprehend. Iwanted so badly to understand.

In 2008, I signed up for the race. Then I finishedit. My six days on the Iditarod Trail had been the most eye-openingand intense experience of my entire life. Amid my bodysslow-motion collapse at the finishing point, I convinced myself Ihad reached my goal a deeper understanding of beauty and strengththat I could reference for the rest of my life. And yet there Iwas, just one year later, riding a bicycle into the Alaskawilderness again.

Next page