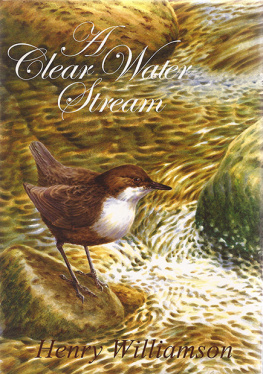

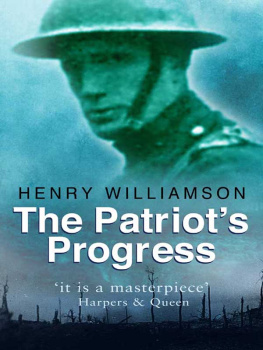

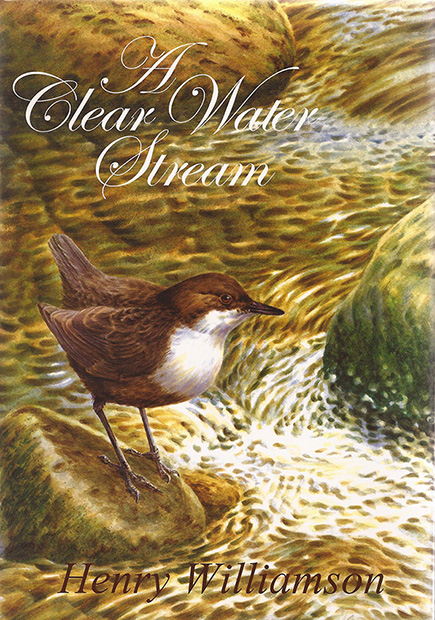

First published in 1958 by

Faber and Faber Limited

New revised, illustrated edition 2008

E-book edition 2013

Smashwords edition

The Henry Williamson Society

14 Nether Grove

Longstanton

Cambridgeshire

Text Henry Williamson Literary Estate 2008

Foreword John Bailey 2008

Illustrations Mick Loates 2008

ISBN 978-1-873507-51-3 (EPUB)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright holders.

In honour of Henry and Loetitia and the Shallowford family

Illustrations

Tailpieces

Bait!

Brown trout rising to the fly

Kingfisher

Old Nog, the heron

Otter chasing trout

Samlet

The Poacher, trout fly

Introduction

I DONT FEEL its strange that Ive been asked to write this introduction. Its more like synchronicity. I was actually bought my first edition copy of A Clear Water Stream in Dulverton in the West Country on a summer holiday in the early 1960s. Unsurprisingly, even as a small child, I became immersed in the book, and the rivers around the hotel where I was staying, that Williamson seemed to be describing for me alone, took on a new fascination. Then, for most of my life, Ive lived a handful or so miles away from Williamsons Norfolk farm. As my obsession with the writer grew, I searched out the older characters who had been acquainted with him and learned from them what the man was like. Or at least what his public persona portrayed. Taciturn perhaps best summarises that.

So, we do have both spiritual and geographical links. When I first began to write, too, I fancied myself as an observer of nature in the Williamson way. Years ago, at university, I had some articles published. I certainly didnt consciously base them on Williamsons work, but you dont have to scratch the surface far to see his influences. Of course, my articles werent nearly as good. It is fine having a turn of phrase, but not if you dont really have much to turn it around. That is what is important about Williamson: whenever he says something, you know he means it and its worth listening to.

I still take A Clear Water Stream on some of my more trying expeditions abroad when I know Im likely to be up against it and, come nightfall, might need a bit of comfort. I was just alive in 1958 when A Clear Water Stream was published and I can dimly remember the England that Williamson was describing. In truth, much of old England had already disappeared, but there were vestiges remaining that werent totally modern and spoiled. There were still wildflowers that hadnt been eradicated by crop spraying. I knew villages that hadnt been swamped by new building. There were plenty of roads that hadnt then become nose-to-tail car parks. A Clear Water Stream, Williamsons account of his stewardship of the stretch of the River Bray at Shallowford in North Devon, where he lived during the 1930s, is about a world of blacksmiths, shepherds, curates, keepers and tenant farmers, a world where drivers of open-top sports cars wear leather coats, goggles, flying helmets and greet each other with a cheery wave. Yes, I like to lie in some rotten part of the world reading this sort of thing, realising there was an age before road rage.

What Ive always sensed and loved about Williamsons work is that he was disarmingly honest and never tried to hide anything from his readers. Or from himself. Take chapter two in the book, The Boy Who Loved Fishing. Can there be a more heartfelt sigh for what is past, anywhere in literature? I had constant friends as a kid, but I was an only child, and there has always been that solitary streak in me that reaches out for that pang of loneliness that pervades Williamsons writing. When Williamson talks about fish in private lakes where peacocks call wildly and rhododendrons flower under towering oaks, I know what he means. I can remember my own pools in summer holidays when time was so fragile and life so precious. I can empathise with Williamson as that boy alone, that boy on whom nature can imprint herself without rival or competition.

Of course, theres much more to Williamson than a welcoming dose of comfort reading harking back to some whimsical Avalon. In his views on society, politics and militarism, he could be controversial but often modern. His environmentalism is certainly so. What he says about the management of a West Country trout stream could be read today in the most advanced journals of the Wild Trout Trust. Take the chapter, The Judges Warning. A more realistic and attractively portrayed interpretation of the aquatic food chain I cant immediately think of. Think, too, of Williamsons work on the river, building groynes and weirs; or of the agonising that went on with his stocking policies; or of his deliberations over the planting of alien weeds. This took place seventy years ago, but it would be up to date even tomorrow. What many of us think we are pioneering we could easily find in Williamson if we bothered to look.

So, writing in 1958, Williamson was living in the past but also in the future. Perhaps its best to say that he lived in his own time and no-one elses. Whatever one thinks about some of the topics Williamson wrote upon, no-one, surely, can ever doubt that he was one of our great naturalists. Its true to say that there have been those who have known more in a pragmatic, scientific sort of way, but none who have felt as much, or as deeply. Theres an intimacy to Williamsons writing that is almost heartbreaking. You feel his gut-churning anxiety over a stranded salmon. His worry over lack of rainfall is so feverish that he writes it with a pain that hurts. Observing and interpreting nature is one thing, but I cant think of anyone but Williamson so driven by its life force, its power and its dignity.

If there is one reason, though, why I will always champion Williamsons name, it is this. Today, in virtually all nature writing and film making, fish are demeaned. Whatever the medium, a bird will be intimately identified. So, too, will reptiles or mammals. We will be told everything we need to know about meercats, Christian names and all, but this is not the case with fish. Endlessly in film or in magazine a fish is quite simply just that, and no-one cares or knows if its a trout or a tarpon.

Yes. Williamson understood fish and loved fish, and wrote wonderfully about fish. And I love him for that. Think back again to chapter two and his perfect description of a small roach. He painted it as the pearl of nature a roach truly is. Think of his tenderness for that old, dark brown trout that he feared constantly to be teetering on the edge of death; or of his admiration for the sparkle of his introduced Loch Levens their vivacity, their colouring, their spotting patterns. Fish are brilliant and Williamson knew that. Thats why for me he will be always worth reading, will always be special.

Like many of Williamsons books, A Clear Water Stream isnt perfect. After all these years, there are pieces Im happy to skip over. But there are many more sections that I can read and re-read and always extract new meaning and new enlightenment. It was my mother, I remember, who bought me