PAUL LAFARGUE (18421911) was born in Santiago, Cuba, and lived there until the age of nine, when his family returned to their hometown of Bordeaux, France. In his early twenties, Lafargue began studying medicine in Paris, but after taking part in a socialist gathering he was barred from the French university system and left the country to pursue his studies in London. There he served as Karl Marxs secretary and married Marxs daughter Laura. Moving back to France in 1870, he participated in the Paris Commune and was again forced to flee the country, first to Spain and then to England. In 1882, after the Communards were granted amnesty, he and Laura returned permanently to France, where Lafargue gained notoriety as a writer of pamphlets and articles on politics and literature, founded the countrys first Marxist labor party, and earned his law degree. On the night of November 26, 1911, he committed rational suicide with Laura at their home near Paris. Lenin spoke at their funeral.

ALEX ANDRIESSE has translated Roberto Bazlens Notes Without a Text and two of four projected volumes of Franois-Ren de Chateaubriands Memoirs from Beyond the Grave. He is the editor of The Uncollected Essays of Elizabeth Hardwick (published by NYRB Classics) and an associate editor at New York Review Books.

LUCY SANTE is the author of, among other books, Low Life, Kill All Your Darlings, The Other Paris, Maybe the People Would Be the Times, and Nineteen Reservoirs. She translated Flix Fnons Novels in Three Lines and has written introductions to several other NYRB Classics, including Paris Vagabond by Jean-Paul Clbert, Classic Crimes by William Roughead, and Nada by Jean-Patrick Manchette. A frequent contributor to The New York Review of Books, she teaches writing and the history of photography at Bard College.

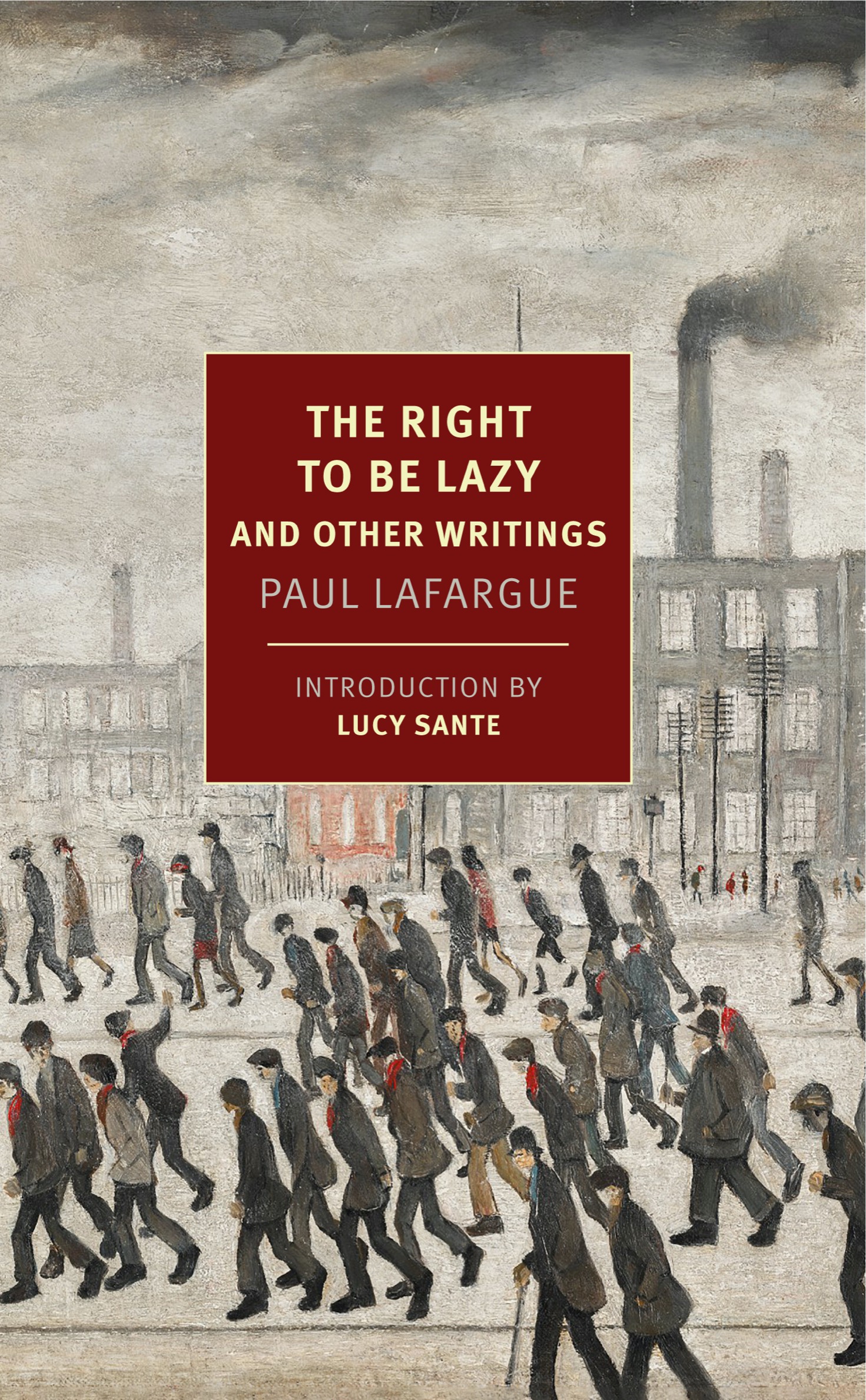

THE RIGHT TO BE LAZY

and Other Writings

PAUL LAFARGUE

Selected and translated from the French by

ALEX ANDRIESSE

Introduction by

LUCY SANTE

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Selection and translation 2023 by Alex Andriesse

Introduction 2023 by Lucy Sante

All rights reserved.

Cover image: L.S. Lowry, Going to the Match (detail), 1928; 2022 The Estate of L. S. Lowry, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS

Cover design: Katy Homans

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lafargue, Paul, 18421911, author. | Andriesse, Alex, translator. Title:

The right to be lazy and other writings / Paul Lafargue; translated from the French by Alex Andriesse.

Other titles: Droit la paresse. English

Description: New York: New York Review Books, [2022] | Series: New York Review Books Classics

Identifiers: LCCN 2022010814 (print) | LCCN 2022010815 (ebook) | ISBN 9781681376820 (paperback) | ISBN 9781681376837 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Hours of labor. | Labor movement. | Socialism. Classification:

LCC HD5106 .L2213 2022 (print) | LCC HD5106 (ebook) | DDC 335dc23/eng/20220525

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022010814

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022010815

ISBN 978-1-68137-683-7

v1.0

For a complete list of titles, visit www.nyrb.com

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

I USED to wish that an enterprising publisher would issue Paul Lafargues The Right to Be Lazy in a pocket edition, with a cover photo of someone drowsily fishing on a riverbank, and sell it from checkout endcaps in supermarkets. But books arent sold that way anymore, and the target audience has mostly died out. Instead Im delighted to be writing the introduction to this new edition, with its clear, stately, inviting translation by Alex Andriesse; its useful annexes; and of course its inclusion in the New York Review Books collection of word-of-mouth classics. The Charles H. Kerr edition, translated by its publisher (not bad, if a bit sepia-toned by now), has been continuously available since 1883 but is much harder to find with the demise of the kind of bookstore that used to stock it. Those were the dissident-Left and anarchist bookstoresthe latter surviving much longer than the former thanks to punk rock. The Kerr edition, with its yellow card-stock cover, its benday portrait of the author, its IBM Selectric typesetting, its rubber-stamped price ($1.25 in 1975), and its prominent printers union logo, would be seen on plywood tables between Max Stirners The Ego and Its Own and Peter Kropotkins Mutual Aid, the anarchists hedging their bets between the right and left wings of their non-organization.

Lafargue, with his long record of battling anarchism in the name of communist orthodoxy, would perhaps be amused by this. He was in fact married to Laura, Karl Marxs second daughter (of four), and both of them in addition could be said to be children of Friedrich Engels, who gave them financial sustenance and stability throughout his life and left them a portion of his estate. Lafargue was born in Santiago de Cuba, in 1842, of mixed heritage (French Christian, French Jewish, Jamaican Indian, and Dominican mulatto) and educated in France. While pursuing medical studies in the early 1850s, he sought out the Left as it was then understood: the resistance to Napoleon III and the peasant anarchism of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. Then he joined the International Working Mens Association and encountered Marx and the veteran revolutionary Auguste Blanqui, who together set him on the path of communism, from which he was never to deviate. He may have been the first to use the term Marxist, earning him a tongue-lashing from Marx, who quipped, If theres one thing for certain, its that I am not a Marxist.

Lafargue began to see a lot of Marx in 1865, when his socialist activities got him banned from the French university system and he was forced to move to London to find work. It was then that he met Laura, and they married three years later. Lafargues charisma, loyalty, and capacity for work propelled him upward in the International, establishing him as a porte-parole for his father-in-law and an enforcer of the correct line. After moving back to Paris, he was active in the Commune, which got him exiled once again, this time to Spain, where he tried to start a communist mass movement but was unsuccessful because of the countrys primitive industrial development at that time, in addition to the influence of visiting Italian anarchists. He moved back to London, where he and Laura lost all three of their children in infancy, and he gave up his medical practice and earned a pittance running a photo studio; Engels had to help them out financially. In 1880, when the Communards were given a general amnesty, the Lafargues moved back to Paris, where Lafargue became the editor of the socialist paper Lgalit and found work at an insurance company. His political activities now and then got him jailed; he revised The Right to Be Lazy while in the Sainte-Plagie prison.

Along with Jules Guesde and Gabriel Deville, he founded the Parti Ouvrier Franais in 1880. In 1891 he was elected to the parliament, representing Lille, the first socialist to enter that body; he was in prison at the time but was released to take his office. Marx had died in 1883, and Lafargue wrote his hagiographical if vivid reminiscences (included here) in 1890, becoming widely known in the movement as the keeper of the flame. His opposition to the social-democratic tendencies of Jean Jaurs marked the beginning of the split between the communists and the socialists. By then he was aging and had begun to detach himself from political activity, reducing his participation to correspondence with socialists abroad, such as Karl Liebknecht and V. I. Lenin, who with his wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya, came to visit the Lafargues in their village. In 1911, when the money from Engels finally ran out, the Lafargues killed themselves with injections of cyanide in a rational suicide pact. Paul was not quite seventy, Laura sixty-six; both were healthy. The suicide pact provoked furious controversy in the international socialist community, but Lenin told Krupskaya, If one cannot work for the Party any longer, one must be able to look truth in the face and die like the Lafargues.