All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

The paper used in this publication is acid-free and meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI z39.481984.

From a single crime know the nation.

Preface

THE LONG, low beams of late afternoon sun poured through the windows as trapped flies tapped at the glass. A strip of flypaper hung above the stairs to the basement where the black coffin rested on sawhorses. The keeper of the mortuary-turned-museum handed me the keys and told me to drop them off at the house next door when I was finished. Then I was alone.

It was a Sunday, a quiet day in Asotin, Washington, a small town on the banks of the Snake River. No one was asking to tour the museum, to walk down the winding stairs into the dark basement and peek into the coffin. I suspected few came here, except local history buffs committed to preserving the stories that have been passed down for generations. The most familiar of those concerned a boy, a gun, and a murder.

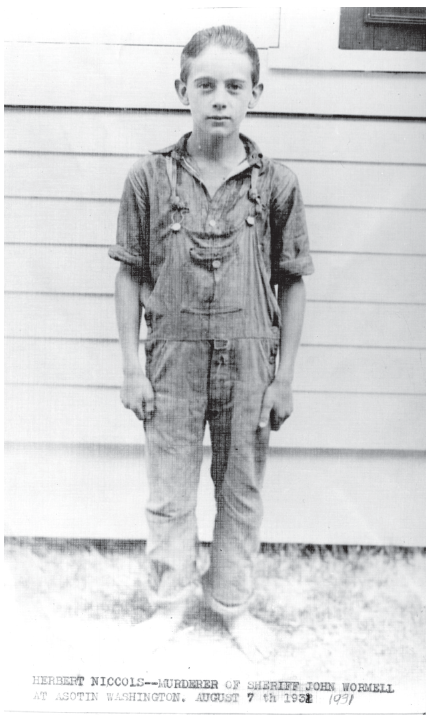

Amid the period dresses, farming implements, branding irons, and embalming tools were photographsone of Sheriff John Wormell, a serious man with a handlebar mustache, and another of a boy in ragtag overalls staring at the camera with a puzzled look. The boy was thin andhad no shoes. He was the reason I was in this dry and dusty town with my twelve-year-old son riding his mountain bike in the soft dirt just outside the museum window.

My fascination with the story began one day when I was at the Indeterminate Sentencing Review Board near Olympia, Washington, reading a file on seventeen-year-old Walter DuBuc. DuBuc attended school through the fifth grade, came from a large family where food was often scarce, and holds the record for being the youngest person in the state to be put to death for murder. In 1932 he was executed in the state's only double execution, his accomplice taking the adjacent place on the gallows. With the exception of a few letters from family members begging the governor for mercy, there was no public outcry. No one questioned why a seventeen-year-old, whose involvement in the crime was minimal, should pay for the death with his life.

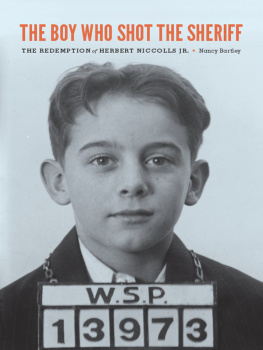

While sifting through files filled with stories of violence, loss, grief, and injustice, I found one concerning a twelve-year-old boy who had been sentenced to prison for life. The case had shocked the nation both for the crime and the punishment. Herbert Niccolls Jr. was regarded as an example of what citizens in 1931 fearedthe increasingly violent youth. Correspondingly, the public became increasingly intolerant.

More than thirty years earlier, Illinois had established a juvenile court to deal with such children, and other states had taken similar measures, including Washington, where DuBuc and Niccolls committed their crimes. The Washington juvenile court system was created in 1905 based on the parens patriae, or government as parent, concept. Like most of the nation's juvenile courts, it began during the Progressive Era, those years of social change early in the twentieth and late nineteenth centuries when laws concerning child labor, mandatory education, and other laws were introduced. The state opened a juvenile reformatory in 1892 but it, like many states' early juvenile courts and reformatories, did not take young murderers.

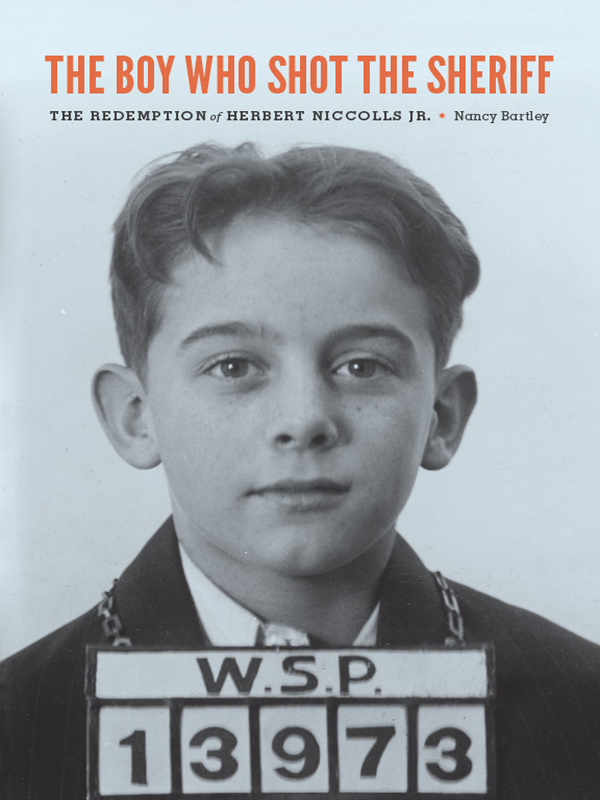

Niccolls's story seemed incomprehensible as I read the yellowed pages of the files, a departure from common sense and reason. A child with ababy face and unruly dark hair posed in typical prison mug shots, full-face and in profile. I would find more about him in the state archivesprison documents, press clippings, and letters written by Washington state governors and scores of citizens. He would become a cause clbre and in the process have every detail of his personal life, from his hygiene to his mental health, open to public discussion.

Niccolls committed his crime during the Great Depression, the bloodiest years in the nation's penitentiaries, when more people were put to death than at any other time in history.

Prisons were filled not only with notorious gangsters but also with those who broke the law simply to provide food and shelter for themselves or their families. Some were too ill or developmentally disabled to defend themselves. In states where sentencing review boards determined when an inmate was released, prisoners could be held for years on charges that today might warrant a one- or two-year sentence. The justice process itself often was corrupt and unconstitutional, from the police investigation to the prosecution and defense. It would be decades before reforms would be made.

That day in Asotin, as I watched my own son ride his bike, I wondered if there ever is a time when a child is beyond redemption. It's a question that is not easily answered. All crime leaves trails of suffering.

Despite the current public belief that violent juvenile crime is a recent phenomenona sentiment common whenever high-profile crimes occurjuvenile crime is not new nor are the defendants younger. A survey of headlines from earlier eras shows how long juvenile crime has been a problem. In 1850, a British fourteen-year-old shot two bullies who had been tormenting him. In 1874, a fourteen-year-old Boston boy killed two and assaulted seven others before he was imprisoned in solitary confinement for nearly the rest of his life. In 1929, a six-year-old Paintsville, Kentucky, boy shot and killed his playmate over the ownership of a piece of scrap iron they had found and were going to sell. This child was convicted of manslaughter but released to his parents on $500 bail. In 2000, a Michigan six-year-old shot his first-grade classmate after she complained that he had spat on her desk. But unlike the Kentucky case,the Michigan boy was not tried. Prosecutors said that what he needed more was to be loved.

A 2003 case from Ephrata, Washington, closely parallels that of Herbert Niccolls Jr. In both, the defendants were twelve years old and considered by judges to be beyond redemption. The crimes drew national attention because the defendants were so young.

The immaturity and impulsiveness of youth, the effects of poverty, violence, and child abuse, and the lack of stable and loving families when children must raise themselves are formulas for juvenile crime at any time. From century to century, generations have always feared nonconformist youth and the demoralization of the young. What changes is our reaction, our laws, and the sentences as the public-opinion pendulum swings from rehabilitative to punitive solutions and back.