Cover and book design by Jonathan Norberg

Edited by Brett Ortler and Ritchey Halphen

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

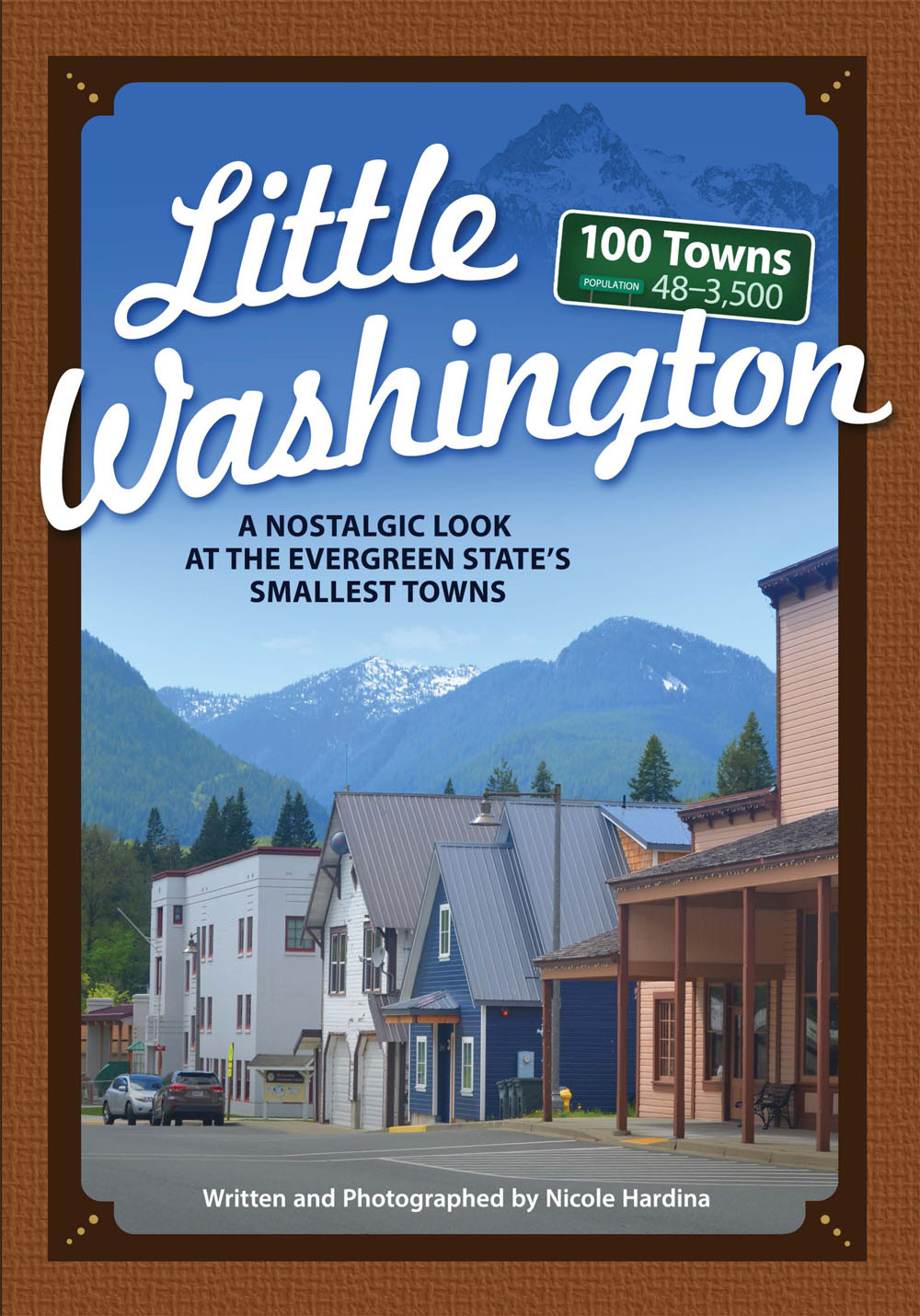

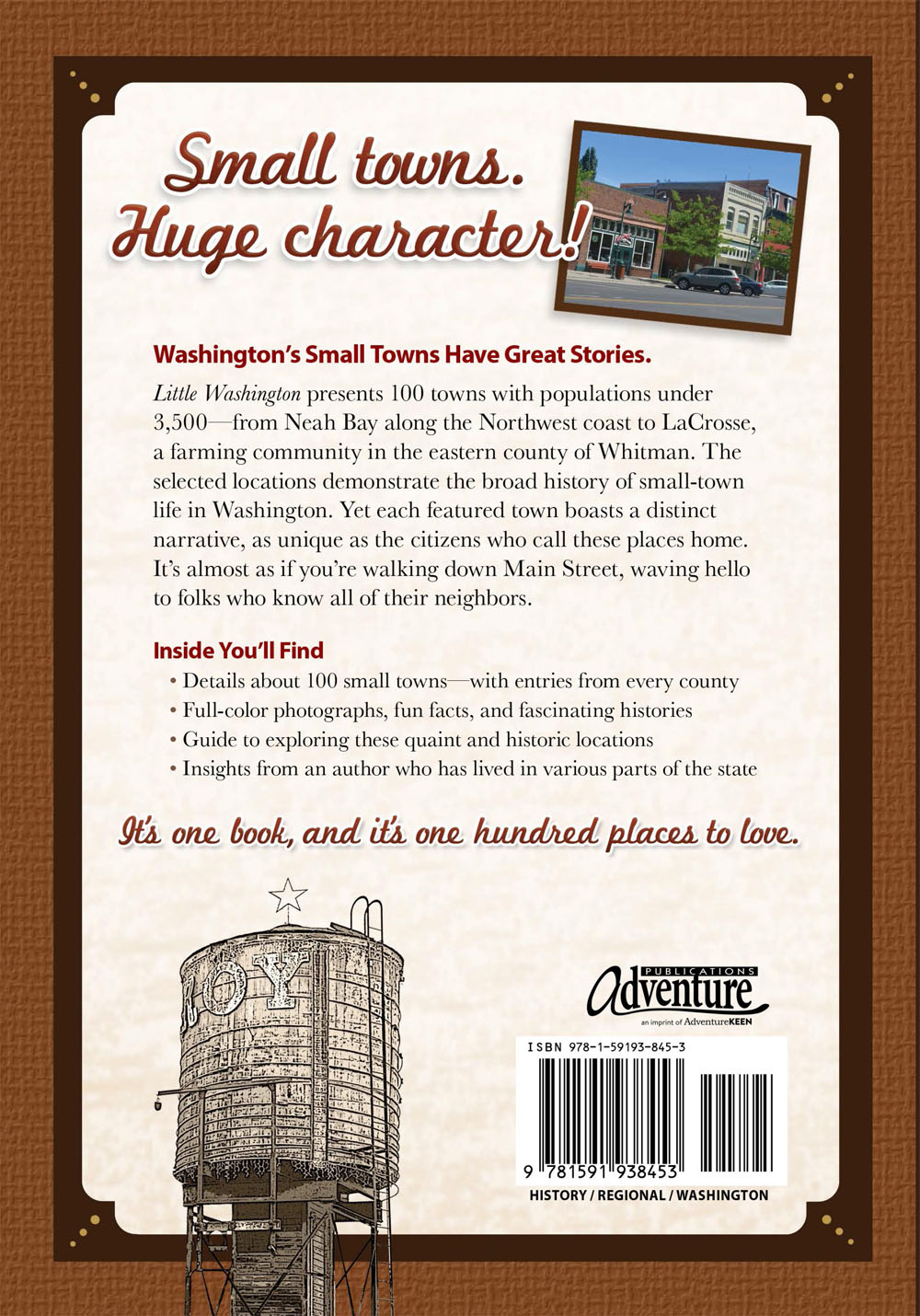

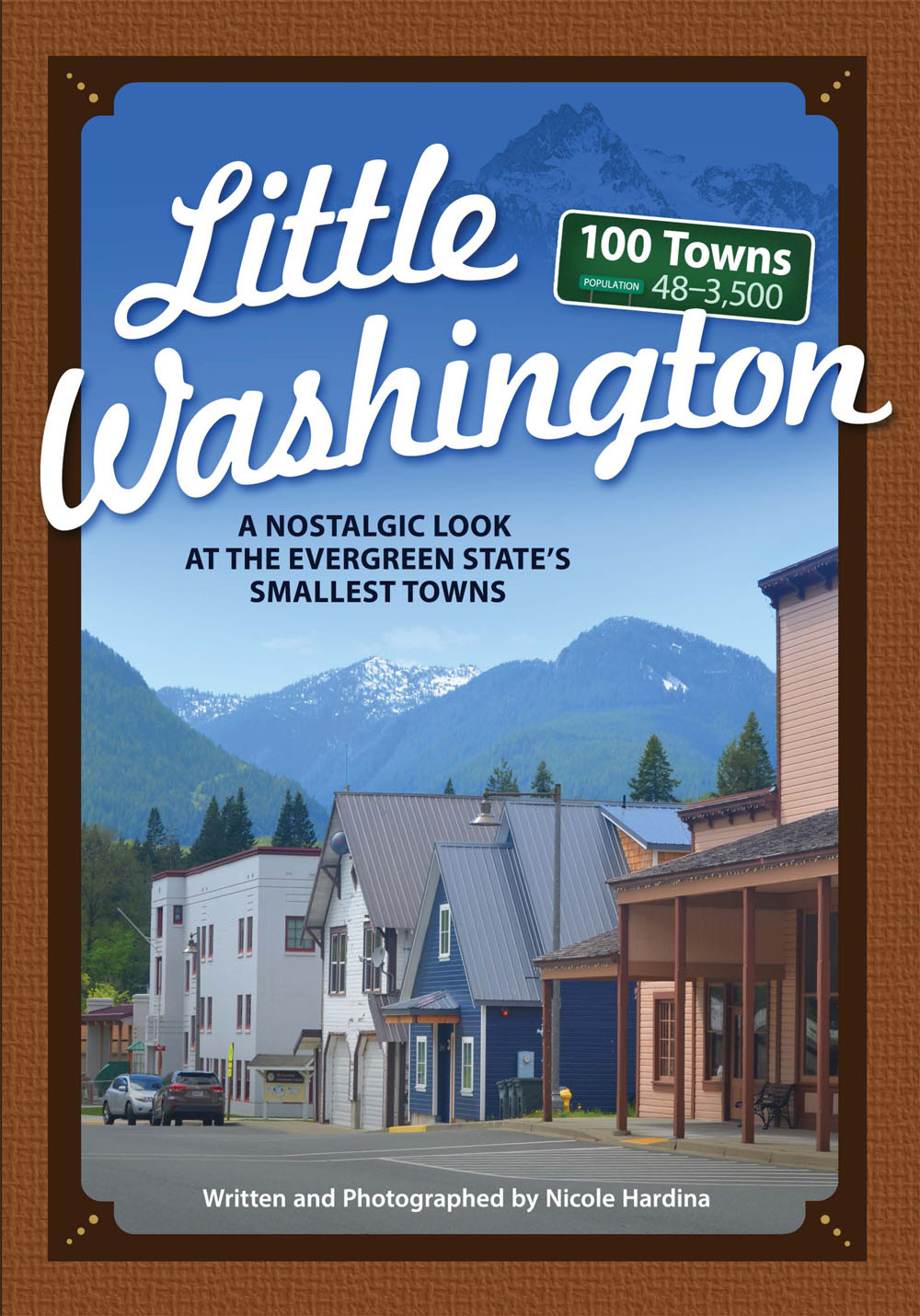

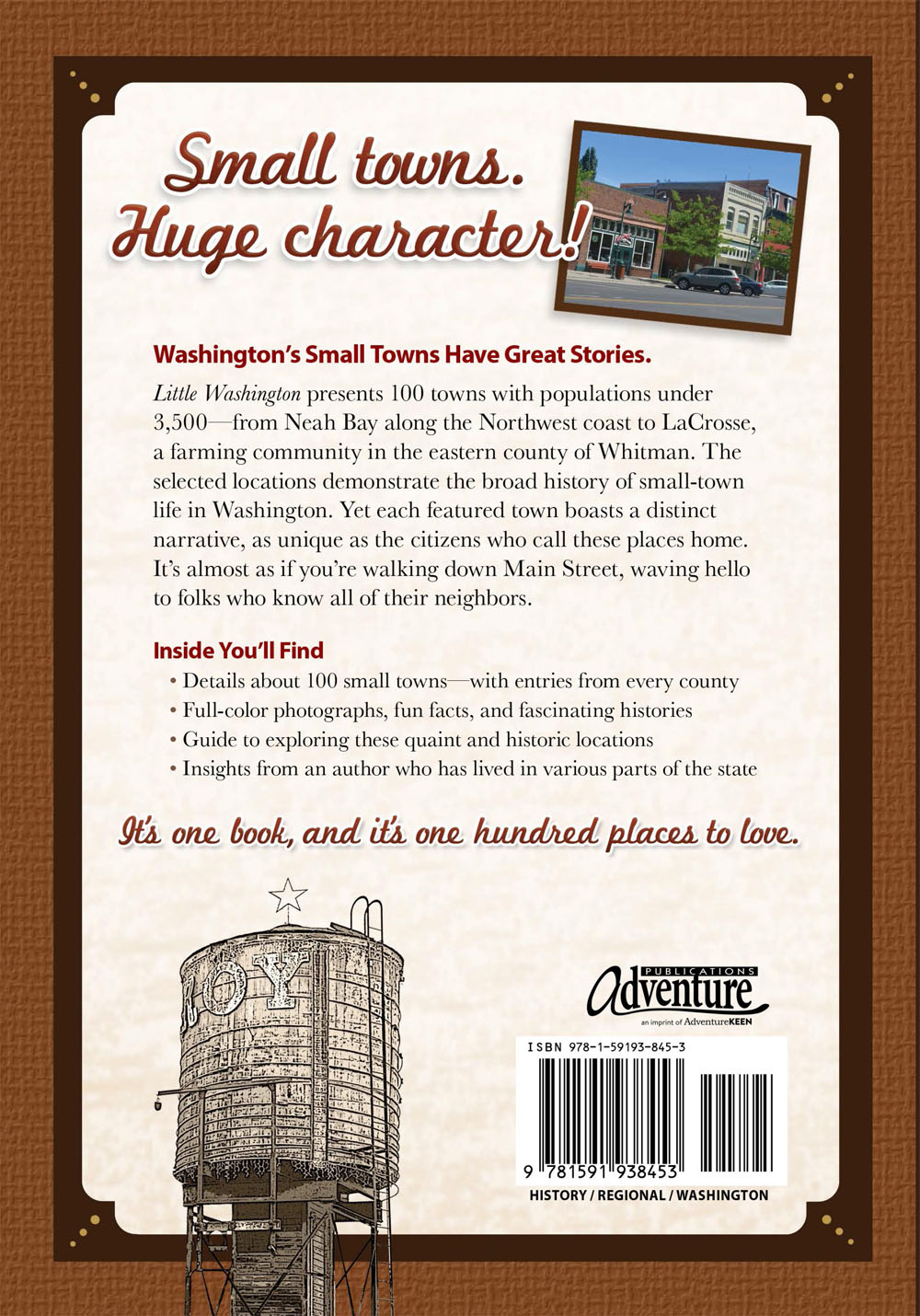

Little Washington: A Nostalgic Look at the Evergreen States Smallest Towns

Copyright 2020 by Nicole Hardina

Published by Adventure Publications

An imprint of AdventureKEEN

330 Garfield Street South

Cambridge, Minnesota 55008

(800) 678-7006

www.adventurepublications.net

All rights reserved

Printed in U.S.A.

ISBN 978-1-59193-845-3 (pbk.); ISBN 978-1-59393-846-0 (ebook)

Dedication

This book is for everyone who takes the shortcut when they know darn well its the long way around.

Acknowledgments

Gratitude and admiration to Gail Kihn of Sumas, Louise Lindgren of Index, Charles Fattig of McCleary, Mayor Dan Rankin of Darrington, all of Shorty Longs kids in Entiat, and many others who shared with me their time, stories, and love for their towns. Thank you for your generosity and your important work.

Thank you to Brett Ortler at Adventure Publications for giving me this project, which came along when I needed it, and thank you to everyone on the team who helped see it through.

Many thanks to Arne, Chelsea, and all the Till writers, and to Smoke Farm for the community, the cold river, and the retreat.

Finally, endless appreciation to those who accompanied me on the journey: Ford Nickel, Laura Krughoff, Cheri Gries, and my parents, Pat and Blake Hardina. Most especially, thank you, Mom. As always, you were with me for the longest miles.

Photo Credits

Photographs by Nicole Hardina except as follows:

Inset photos identified by page in a left to right order using a, b, c, d.

202d, U.S. Forest Service-Pacific Northwest Region: This image is licensed under Public Domain Mark 1.0, which is available at https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/mark/1.0/

116c, Edmund Lowe Photography/Shutterstock.com

Table of Contents

Introduction

Dear Reader,

I grew up in an Alaskan town where back roads connected to a few state routes running along a narrow peninsula. Since I moved to Washington in 1997, most of the traveling Ive done in this state has been on its biggest freeways. That changed for me when I began writing this book.

Now Ive traveled the length of the Columbia Gorge and the glacial-cut valleys of the Colville National Forest. After all this time living here, I finally visited the Palouse Falls, in my research, I learned that they are Washingtons official state waterfall, thanks to the advocacy of nearby Washtucnas schoolkids. I talked to farmers, local historians, mayors, librarians, business owners, and some kids eating Popsicles, wondering why I was taking pictures of their town. I stood on Kamiak Butte, listening to birdsong over a green ocean of wheat. I learned about the provenance of phrases like jerkwater town and the namesakes of counties, roads, and monuments, controversial and otherwise. I learned that some towns celebrate the Indigenous contributions to their existence, while others push them to the background or bury them altogether. I did my best to approach each community with open eyes and a spirit of curiosity.

What can you really know about a community from the outside? Not enough, I readily admit. There is more to each of these places than I am able to offer here. Still, I know so much more than I did before. The library in Darrington offers classes in the Lushootseed language. The Farmers Daughter in Kahlotus is owned and run by an actual farmers daughter. Mount Index existed on a map well before Persis Gunn said she named it.

I live on the traditional land of the Duwamish, the first people of Seattle, whose case to restore federal recognition began in 1978 and remains pending today. With each visit, conversation, and hour of research, I understood and appreciated Washington State more.

This project began with a list of incorporated towns with fewer than 1,000 residents, but that approach provided a limited perspective. Jefferson County is more than Port Townsend; its also home to the Hoh Rainforest and a dozen or so unincorporated towns like Quilcene, with a few hundred people and an enormous oyster hatchery, and Mount Walker, the only mountain facing Puget Sound that visitors can summit on foot or in a car. In the end, the project expanded to include communities spanning all 39 counties.

Little Washington is my attempt, a 100 times over, to get to know the state I call home. Its part history, part travelogue, and all love letter to the Evergreen State. When I tell people about this book, they almost always ask me which town is my favorite. I could tell you mine, but I hope that after reading this, youll want to find your own answer.

Nicole

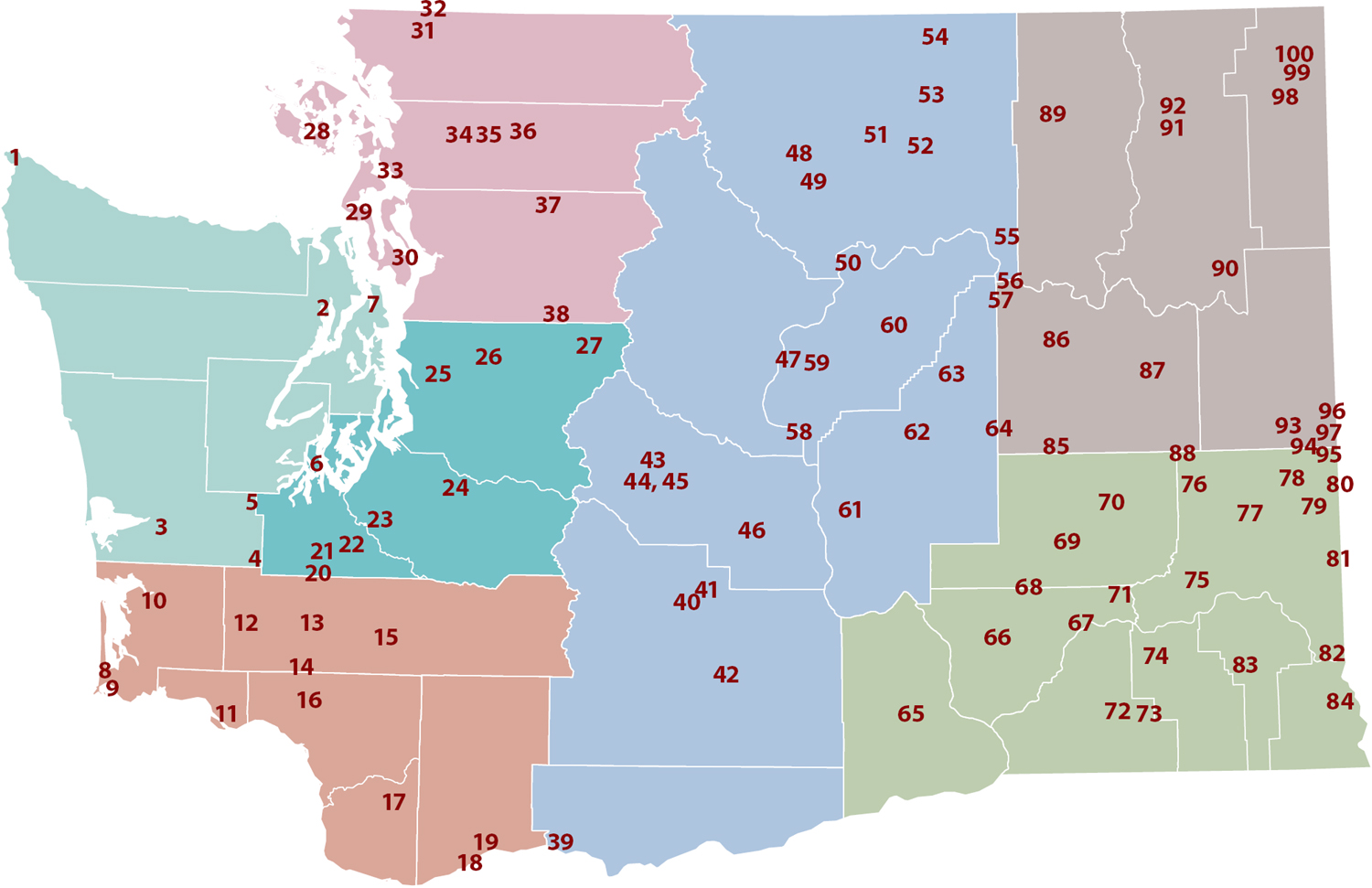

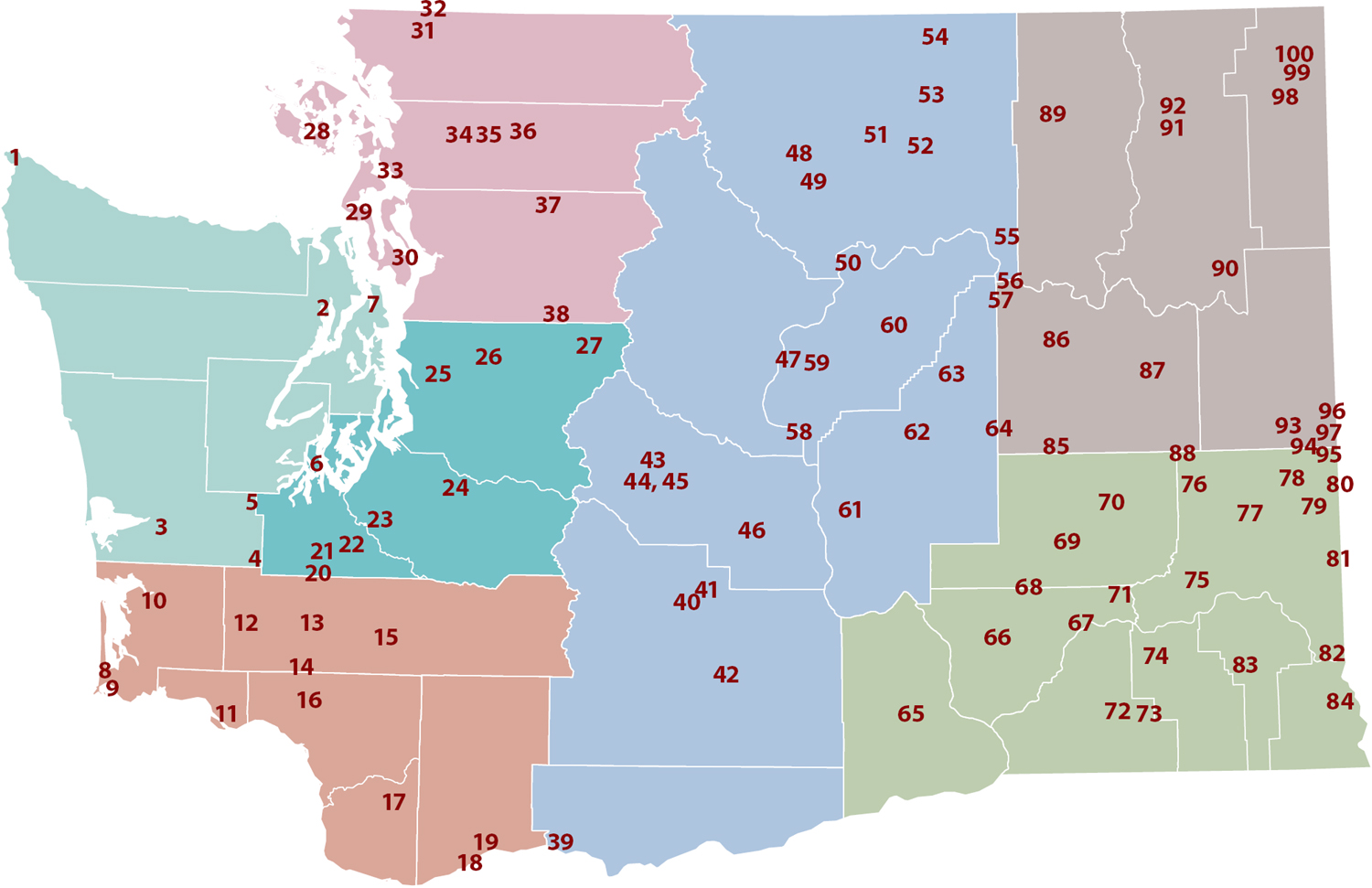

Locator Map

Neah Bay

TOP: The Makah symbol shows Thunderbird carrying a whale.

Population: 994

Unincorporated

INSETS L to R: Boardwalks protect the forest floor on the hike to Shi Shi Beach. Erosion continues to shape Cape Flatterys coastline. Fort Nez Gaona-Diah honors Makah veterans and remembers Spains early attempt to colonize the area. Neah Bay offers fishing charters for several species of fish, including salmon, halibut, and lingcod.

People of the Cape

The community of Neah Bay is home to the Makah Tribe and located on the Makah Reservation. The Makah, whose name variously translates as people of the cape and people who are generous with their food, inhabit their traditional lands, minus the 300,000 acres they lost in the 1855 Treaty of Neah Bay. But unlike treaties between Washingtons territorial governor, Isaac Stevens, and other Indigenous groups, the Treaty of Neah Bay affirmed the Makah peoples rights to maintain their villages and lifeways, including whaling, sealing, and fishing, on land the Makah did not cede.

Sixty years prior to the treaty, Salvador Fidalgo established the first non-Native settlement in Neah Bay, but it failed within a year after conflict with the British. The area now known as Neah Bay was at the time called Deah (or Diya in Makah), named for Makah Chief Dee-ah. Deah was one of five permanent Makah villages that stretched along the northern and western coasts of what became Washington State.

PreEuropean contact, as many as 4,000 Makah lived in these villages. Cedar longhouses 30 feet wide and 70 feet long housed multiple generations of extended families. Summer brought travel to Tatoosh Island, Ozette Lake, and other seasonal camps, fishing grounds, and gathering places. The Makah designed canoes made from western red cedar for whaling, fishing, and war. Selling baskets woven from cedar and grasses became a source of income for the Makah after the treaty and remained important into the 20th century.

Next page