Includes bibliographical references and index.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-77108-072-9 (pbk.).ISBN 978-1-77108-073-6 (pdf).

ISBN 978-1-77108-075-0 (mobi).ISBN 978-1-77108-074-3 (epub)

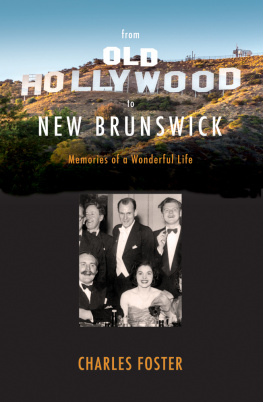

1. Foster, Charles, 1923-. 2. Public relations consultantsUnited

StatesBiography. 3. CelebritiesPublic relationsUnited States. 4. ScreenwritersUnited StatesBiography. 5. SpeechwritersCanadaBiography. 6. JournalistsNew BrunswickBiography. 7. Performing artsUnited StatesHistory. 8. Hollywood (Los Angeles, Calif.)Biography. I. Title.

Nimbus Publishing acknowledges the financial support for its publishing activities from the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF) and the Canada Council for the Arts, and from the Province of Nova Scotia through the Department of Communities, Culture and Heritage.

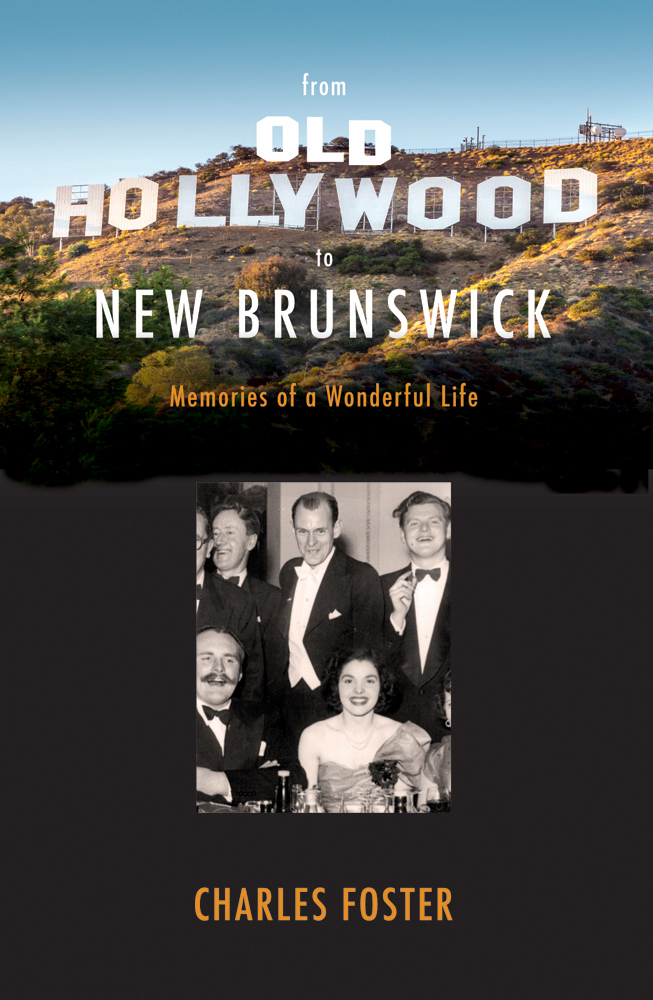

Jimmy Edwards (lower left) and Benny Hill (top right) were guests of my wife, Irene, and I at a banquet in London in the 1950s. I met Jimmy while in the RAF in Moncton and Benny Hill on Central Pier in Blackpool, England, where he was beginning his fabulous career in 1952.

PROLOGUE

It was on Thursday, July 16, 1936, that I first realized Atlantic Canada existed. On that memorable day, a very important Atlantic Canadian who had reached his pinnacle of success in England spent more than two hours extolling the wonders of this unique part of North America to a very unimportant person, me.

Born William Maxwell Aitken in Maple, Ontario, in 1879, his family had moved to Newcastle, New Brunswick, when he was under a year old. It was there he published his first newspaper when he was only thirteen. He graduated with honours from high school in Newcastle and had registered at Dalhousie University and Kings College but did not attend either. He attended the University of New Brunswick briefly before quitting to become a clerk in the Chatham, New Brunswick, office of lawyer Richard Bennett, who later became prime minister of Canada. A visit to Halifax when he was eighteen introduced Aitken to John F. Stairs, who gave him a job in the Stairs familys finance business. When Stairs died in 1904, Aitken, who had demonstrated an astonishing ability to handle huge financial undertakings, took over the company, Royal Securities.

In 1906 Max Aitken married Haligonian Gladys Drury. It was a happy marriage that lasted, sadly, only until 1927, when Gladys died from cancer at age forty-one. By then, the Aitkens, having made a great deal of money in Halifax in a variety of Canadian financial ventures, were in London, England, where Aitken had shown that Atlantic Canadians were equal in brainpower to anyone anywhere in the world. He had taken over one of Englands national daily newspapers, the Daily Express , when it was foundering. By changing the papers entire policy hed made it the largest and most successful in the country, with a circulation of more than three million copies per day.

Aitken had also become a MP for Ashton-under-Lyne in Lancashire and in business became a major shareholder in the growing Rolls-Royce Ltd. During the First World War he had been put in charge of the Canadian War Records Office and was knighted in 1911 by King George V for his work to strengthen England. But he did not forget his Canadian roots. During the war he took charge of recording the success stories of Canadians and made sure they were well publicized in both Britain and Canada. By this time Aitken owned four British newspapers, including the LondonEvening Standard . In 1917, as a result not only of his business successes but for his quiet generosity and good work for those in need, Aitken was elevated to the peerage. As Lord Beaverbrook, he took his seat in the prestigious British House of Lords.

Why I, in 1936, at the age of thirteen, was talking to this remarkable gentleman is a proud memory I will recall later. But my introduction to the wonders of Atlantic Canada began on a very rough sea trip from Dover in Kent, England, to Calais, France, as I sat beside Lord Beaverbrook en route to yet another countryGermanywhere something very important was about to take place.

Lord Beaverbrook was the first Atlantic Canadian I had ever met. But to this day, I remember him telling me that despite his successes in England nowhere else in the world would ever eclipse his memories of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. You must go there one day, he said. If you do, tell them I will one day do something to say thank you for the start I received there in my life.

He certainly kept that promise. After the Second World War ended, Lord Beaverbrook became chancellor of the University of New Brunswick and while in Fredericton, apart from many large donations to the university, he funded the building of the Beaverbrook Art Gallery and filled it with priceless art. He also built the Fredericton Playhouse, the Lord Beaverbrook Hotel, and the Lady Beaverbrook Arena. He provided millions for scholarships to the university, and spread his generosity to places like the Miramichi where he built the Lord Beaverbrook Arena. A school in Campbellton, New Brunswick, exists because he gave the city the funds, and his foundation of the Beaverbrook Chair in Ethics and Communications at McGill University came from his love of Canada and of Canadians. It would take a lot more space to include all his other efforts to say thank you to Atlantic Canada, but it must be included that Saint John still boasts the Lord Beaverbrook Rink.

During the Second World War, Seven years after meeting Lord Beaverbrook, I visited New Brunswick. In 1943 the Royal Air Force (RAF) shipped me across the Atlantic to New York on the mighty Queen Elizabeth , and from there we travelled by train to 31 Personnel Dispatch Centre in Moncton, where we awaited our turn to be sent out west for flight training. It was my experience in Moncton during those six weeks that brought me back again in 1970 for what I anticipated would be another six weeks.

After forty-three years I am still here.

My wife and I have enjoyed every day of those years and have told many people, including our son, Ian, that nowhere else in the world offers the friendliness and opportunities of Atlantic Canada. Ian and his wife, Sheila, moved here five years ago and are now spreading the same enthusiasm for our region.

I havent made the millions that Lord Beaverbrook achieved, nor have I contributed to this part of the world as he later did, but I have learned that what he told me in 1936 is absolutely correct: Atlantic Canada is undoubtedly the best place in the world to live. Since that first meeting with Lord Beaverbrook. I have talked to many other expatriate Atlantic Canadians. One who stands out is the man who made Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) Studios in Hollywood the most illustrious and lasting of all time: Louis B. Mayer. I recall Mayer telling me it was the work ethic he learned in his fathers scrap metal yard in Saint John, New Brunswick, that taught him compassion for other workers and showed him many more abilities not learned in schoollike concern for every employeethat made him successful in Hollywood.