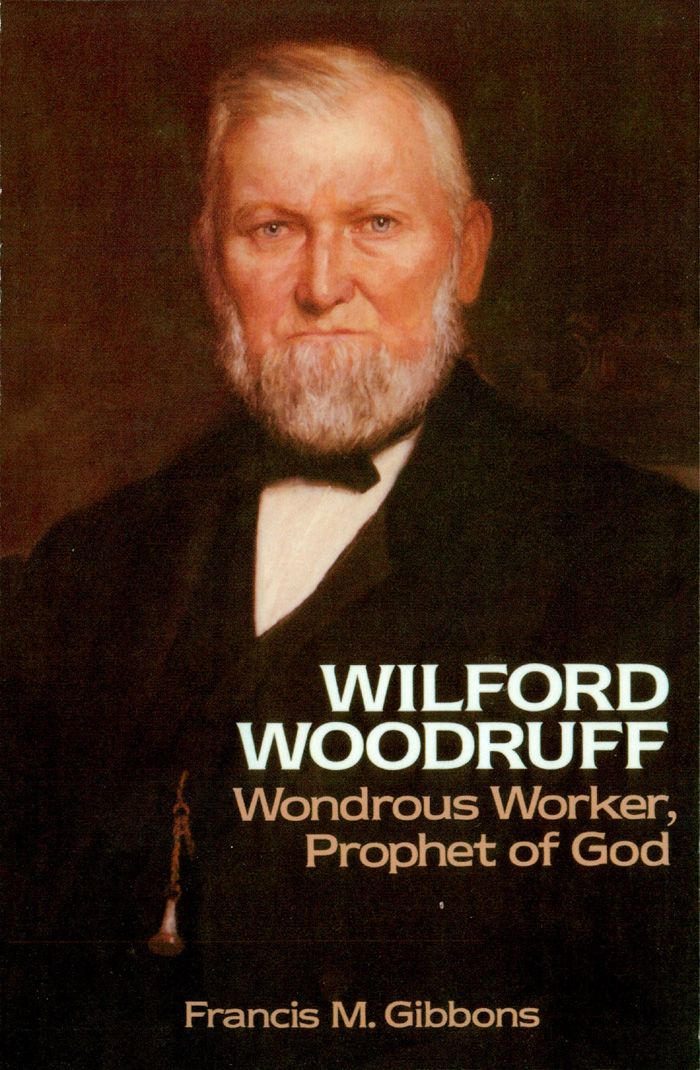

T he extensive journals of President Wilford Woodruff were written mostly in his own hand. Often the entries were made under difficult circumstances and under heavy time pressures. Moreover, his lack of formal training in English composition, spelling, and punctuation often resulted in many technical errors. To make the reading of the text go more smoothly, obvious errors in punctuation and spelling have been corrected. Such changes, however, have not altered the substance or meaning of the quoted excerpts.

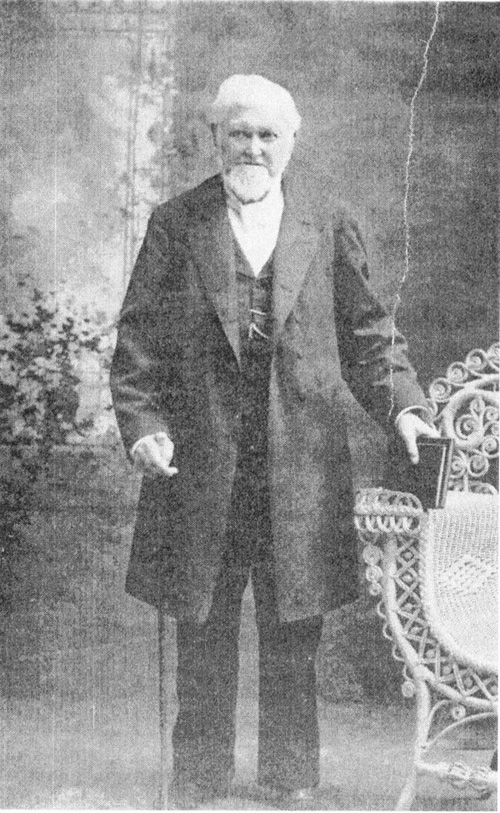

Permission to reprint the pictures included in the book was granted by the Historical Department of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and by Anna Packer, a great-great-granddaughter of President Woodruff.

Permission to quote from the typescript copy of President Wilford Woodruffs journals (in nine volumes, edited by Scott G. Kenney) was graciously given by Signature Books of Midvale, Utah, in a letter dated August 27, 1985, from Gary J. Bergera, publisher, which stated that Signature Books owns all literary rights to the diaries. Ruth Bay Stoneman and Allen B. Stoneman provided excellent research assistance, and Daniel B. Gibbons coordinated final efforts leading to publication. Anna Packer and Emma Rose Christiansen, a granddaughter of President Woodruff, furnished important family perspectives. Glenn M. Rowe of the Church Historical Department kindly cooperated in arranging for the reproduction of pictures from the Church archives. And the editorial staff of Deseret Book Company, especially Jack Lyon, were most helpful and considerate. To these and many others go heartfelt thanks, along with an acknowledgment of the continuing influence of The Mentor.

Chapter One

The Seeds

L ongevity, industry, and spirituality are the qualities that best describe Wilford Woodruff, the fourth president of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The first two qualities were a legacy from his lineal ancestors.

But the third appears to have been an inherent endowment that did not descend from his earthly fathers.

Josiah Woodruff, Wilfords great-grandfather, lived almost a hundred years, performing manual labor up to the time of his death. The grandfather, Eldad Woodruff, who was born in 1751, had the reputation of being the hardest worker in the county. And Wilfords father, Aphek Woodruff, who was born November 11, 1778, began to work in a flour mill and sawmill at age eighteen and stayed at his task for a half century, most of the time laboring eighteen hours a day. The mother, Beulah Thompson, who died at a comparatively young age of spotted fever, was, nevertheless, descended from a hardy line of New England Yankees. She passed away when Wilford was only fifteen months old.

Against such a background, one with only nominal foresight could have predicted when Wilford Woodruff was born March 1, 1807, in Farmington, Hartford County, Connecticut, that he would be long lived and that he would be a worker. But who could have predicted that this infant, commencing at an early age, would manifest an extraordinary spiritual sensitivity and that in his maturity he would become a prophet of God, endowed with spiritual powers and perceptions that seemed almost to pierce the veil between time and eternity? From what is now known, there was no one on President Woodruffs immediate ancestral lines, as there was, for instance, among the ancestors of Joseph Smith, who had shown special spiritual or prophetic propensities. There was no one such as an Asael Smith who had predicted that a prophet of renown would be born in his line; or a Joseph Smith, Sr., who received many unusual visions and revelations; or a Solomon Mack who experienced a striking spiritual conversion in his old age.

Although Wilford Woodruffs ancestors do not appear to have been blessed with that spiritual fervor and sensitivity so evident in him, they were honest, God-fearing people who subscribed to the forms of religion as taught by the Presbyterian sect and who preached Christianity through their conduct. It was said of Aphek, the father, for instance, that he made himself poor by giving to the poor. Being a man of charity and integrity, he seldom declined the request of a neighbor for a loan, or to become surety for the repayment of a loan, or for some other assistance or gratuity. And at age sixty, he accepted the gospel as taught by his son and was baptized into the Mormon Church by him. Wilfords teaching and baptizing his father was both an expression of love for the one who had given him earthly life, and of gratitude for the way in which the father had nurtured him into respectable manhood. And the process was not an easy one for the father.

In the first place, when Beulah died, Aphek was left a widower with three little boys: Azmon, age six; Thompson, who was four; and baby Wilford. Not long afterward, the father married his second wife, Azubah Hart, who, in time, bore him six children. With a family of nine, Aphek and Azubah were hard put merely to provide the necessities for them, let alone to give each child any semblance of individualized attention. On this account, Wilford and the other children learned early in life the lessons of independence and self-reliance, being subtly taught the principles of industry and integrity by the example of the parents.

In the second place, Wilford proved to be a most difficult child to rear. It was not that he was disobedient or disrespectful; he was simply accident prone. The boy seemed to have a magnetic attraction to danger and adversity. On reading the following compendium of Wilford Woodruffs accidents and injuries, the first inclination is to disbelieve it because of its improbability. But given the mans absolute sense of integrity, one is finally forced to the realization that all this really happened to one person: At age three he fell into a tub of scalding water that burned him so badly his survival was in doubt for nine months. Three years later Wilford fell on his face from a high beam in the barn, where he was playing with Azmon and Thompson. Not long afterward, he fell downstairs in the family home, breaking an arm. Then came an encounter with a bull that almost gored him. And a visit to Uncle Eldads about this time resulted in a fracture of the other arm when he fell from a porch. As if to negate the idea of partiality to arms, he then fractured a leg while playing around the family sawmill. In close succession followed a kick in the abdomen by an ox; a fall from a hay wagon with the load toppling on top of him; an accident when a wagon overturned on him and his father; and a fifteenfoot fall on his back from a tree. When he was twelve, Wilford almost drowned in the Farmington River. A year later, he almost froze to death after falling asleep in a blinding snowstorm, but he was saved by a man who found and awakened him. Then at age fourteen he split his left instep open with an ax. A year later he was bitten on the hand by a dog with hydrophobia. At age seventeen he was thrown from a horse, breaking a leg and disjointing his ankles. When he was twenty, Wilford narrowly missed being crushed by the wheel of a flour mill. And four years later, he had a similar close call. The day of his baptism, December 31, 1833, his horse kicked the hat off his head, narrowly missing what could have been a fatal or seriously damaging blow. Ten minutes later, as he left the baptismal pond, he was thrown from a sled beneath the feet of a team of horses and was dragged for some distance. While traveling with Zions Camp in 1834, Elder Woodruff narrowly missed being shot when the ball from a gun that had been fired accidentally passed within a few inches of his breast. A few months later, a loaded musket pointed at his breast misfired. In 1839 he was dragged for a half mile by a team of horses that spooked when a bolt came out of the coupling-pole of his wagon, separating the front and rear wheels. And in 1846, while the Camp of Israel was at Winter Quarters, he was severely injured when a tree fell on him.