THE

Sin-eater

Also by Thomas Lynch

FICTION

Apparition & Late Fictions (2010)

POETRY

Skating with Heather Grace (1987)

Grimalkin & Other Poems (1994)

Still Life in Milford (1998)

Walking Papers (2010)

NONFICTION

The Undertaking

Life Studies from the Dismal Trade (1997)

Bodies in Motion and at Rest

On Metaphor and Mortality (2000)

Booking Passage

We Irish and Americans (2005)

THE

Sin-eater

___________

A BREVIARY

THOMAS LYNCH

WITH PHOTOGRAPHS BY MICHAEL LYNCH

The Sin-eater: A Breviary

Copyright 2011 by Thomas Lynch

ISBN 978-1-55725-872-4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lynch, Thomas, 1948

The sin-eater : a breviary / Thomas Lynch ; with photographs by Michael Lynch.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-55725-872-4

I. Title.

PS3562.Y437S46 2011

811.54--dc22 2011010839

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in an electronic retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any otherexcept for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Published by Paraclete Press

Brewster, Massachusetts

www.paracletepress.com

Printed in the United States of America

Contents

THIS BOOK IS FOR

J.J. MCMAHON

AND IN MEMORY OF SONNY CAR MODY

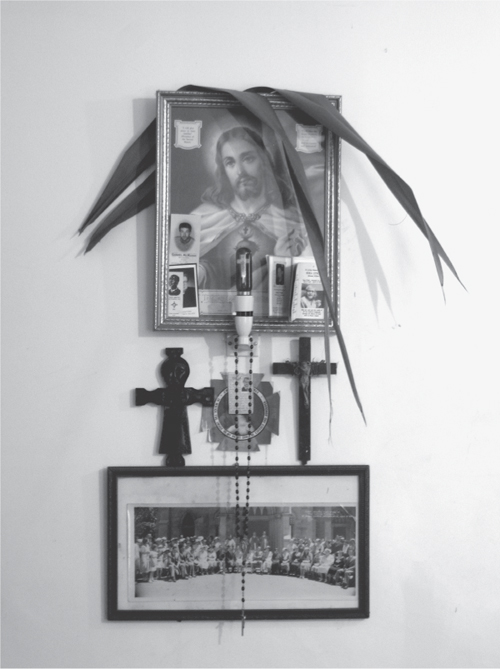

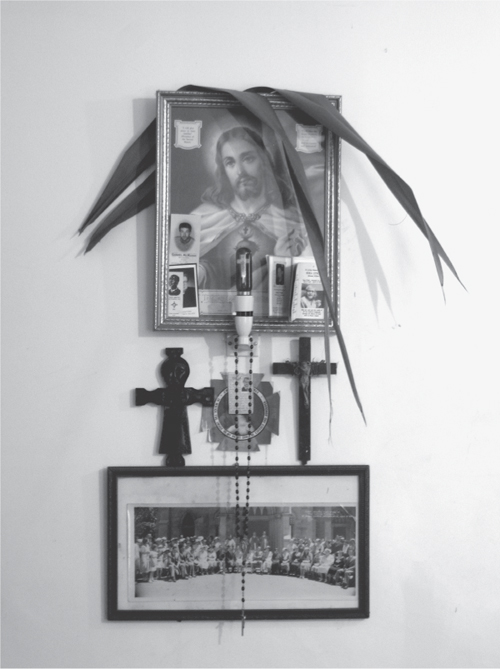

KITCHEN SHRINE MOVEEN

Introit

Si comprehendis, non est Deus.

AUGUSTINE OF HIPPO

A rgyle, the sin-eater, came into being in the hard winter of 1984. My sons were watching a swashbuckler on T.V. The Master of Ballantrae based on Robert Louis Stevensons novel about Scots brothers and their imbroglios. I was dozing in the wingback after a long day at the funeral home, waking at intervals too spaced to follow the narrative arc.

But one scene I half wakened tothe gauzy edges of memory still give wayinvolved a corpse laid out on a board in front of a stone tower house, kinsmen and neighbors gathered round in the grey, sodden moment. Whereupon a figure of plain force, part pirate, part panhandler, dressed in tatters, unshaven and wild-eyed, assumed what seemed a liturgical stance over the body, swilled beer from a wooden bowl, and tore at a heel of bread with his teeth. Wiping his face on one arm, with the other he thrust his open palm at the woman nearest him. She pressed a coin into it spitefully and he took his leave. Everything was grey: the rain and fog, the stone tower, the mourners, the corpse, the countervailing ambivalences between the widow and the horrid man. Swithering is the Scots word for itto be of two minds, in two realities at once: grudging and grateful, faithful and doubtful, broken and beatifiedcaught between a mirage and an apocalypse. The theater of it was breathtaking, the bolt of drama. I was fully awake. It was over in ten, maybe fifteen seconds.

I knew him at once.

The scene triggered a memory of a paragraph Id read twelve years before in mortuary school, from The History of American Funeral Directing by Robert Habenstein and William Lamers. I have that first edition, by Bulfin Printers of Milwaukee circa 1955.

The paragraph in Chapter III, page 128 at the bottom reads:

A nod should be given to customs that disappeared. Puckle tells of a curious functionary, a sort of male scapegoat called the sin-eater. It was believed in some places that by eating a loaf of bread and drinking a bowl of beer over a corpse, and by accepting a six-pence, a man was able to take unto himself the sins of the deceased, whose ghost thereafter would no longer wander.

The Puckle referenced was Bertram S. Puckle, a British scholar, whose Funeral Customs, Their Origin and Development would take me another forty years to find and read. But the bit of cinema and the bit of a book had aligned like tumblers of a combination lock clicking into place and opening a vault of language and imagination.

__________

I was raised by Irish Catholics. Even as I write that it sounds a little like wolves or some especially feral class of creature. Not in the nineteenth century, nativist sense of brutish hordes and apish drunkards, rather in the sense of sure faith and fierce family loyalties, the pack dynamics of their clannishness, their vigilance and pride. My parents were grandchildren of immigrants who had all married within their tribe. Theyd sailed from nineteeth-century poverty into the prospects of North America, from West Clare and Tipperary, Sligo and Kilkenny, to Montreal and Ontario, upper and lower Michigan. Graces and OHaras, Ryans and Lynchesthey brought their version of the one true faith, druidic and priest-ridden, punctilious and full of superstitions, from the boggy parishes of their ancients to the fertile expanse of middle America. These were people who saw statues move, truths about the weather in the way a cat warmed to the fire, omens about coming contentions in a pair of shoes left up on a table, bad luck in some numbers, good fortune in others. Odd lights in the nightscape foreshadowed death; dogs eyes attracted lightening; the curse of an old spinster could lay one low. The clergy were to be given whats going to them, but otherwise, not to be tampered with. Priests were feared and their favor curriedtheir curses and their blessings opposing poles of the powerful medicine they were known to possess. The only moderating influence to this bloodline and gene pool was provided by my paternal grandmother, a woman of Dutch extraction, who came from a long line of Daughters of the American Revolution. She was a temperate, Methodist, an Eisenhower Republicanshe voted for him well into the 1980sa wonderful cook and seamstress and gardener who never gossiped or gave any scandal to her family until early in the so-called roaring twenties, when she was smitten by and betrothed to marry an Irish Catholic. This was not good news to her parents and their circle. As was the custom of her generation, and to appease his priest, she converted to what she would ever after refer to as, the one true faith?the lilt appended to the end of the declarative easing a foot of doubt into the door of surety, as if the apostle with a finger in the wounds of the risen Christ had queried, My Lord, My God? She took a kind of dark glee in explaining the conversion experience to her grandchildren, to wit: Ah, the priest splashed a little water on me and said, Geraldine, you were born a Methodist, raised a Methodist... Thanks be to God, now youre Catholic. Some weeks after the eventual nuptials, she was out in the backyard, grilling sirloins for my grandfather on the first Friday in Lent, when one of the brother knights from the K. of C. leapt over the back fence to upbraid her for the smell of beef rising over a Catholic household during the holy season. And she listened to your man, nodded and smiled, walked over to the garden hose, splashed water on the grill and said, You were born cows, raised cows... thanks be to God, now you are fish. Then sent the nosey neighbor on his way. Surely, we are all Gods children, she would append to her telling this, the same but different.