THIS BOOK WAS DIGITALLY PRINTED.

Foreword

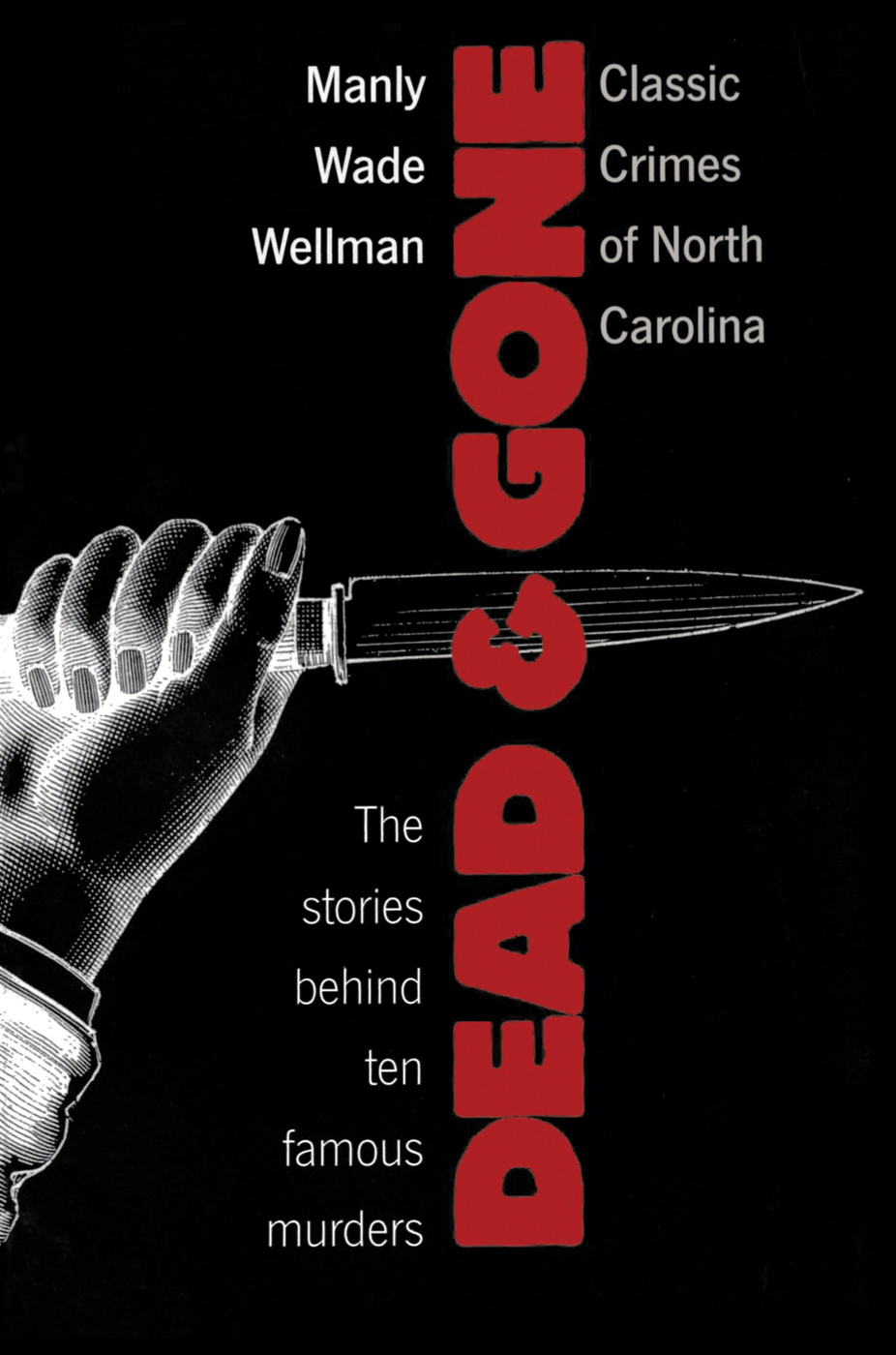

P EOPLE BEGIN TO SEE , pronounces Thomas De Quincey in his lecture On Murder Considered As One of the Fine Arts, that something more goes to the composition of a fine murder than two blockheads to kill and be killeda knifea purseand a dark lane. Later in the same work, he develops the viewpoint: Everything in this world has two handles. Murder, for instance, may be laid hold of by its moral handle (as it generally is in the pulpit, and at the Old Bailey); and that, I confess, is its weak side; or it may also be treated aesthetically, as the Germans call itthat is, in relation to good taste.

This attitude would have seemed curiously hyper-sophisticated to the forthright North Carolinians of the nineteenth century, when most of the events considered here took place. Yet these ten murders were each the object of tremendous and widespread interest among the masses of people, who, Tolstoi repeatedly assures us, are the critics most to be respected. Nor was this preoccupation due to any rarity of homicides there and then. For instance, from 1811 to 1815, North Carolina courts tried eighty-nine charges of murder, at a time when the states population was less than 600,000, with only occasional small urban concentrations and no notable reputation for neuroses. Nor does that figure include manslaughters or unsuccessful attempts, or cases of escape from justice, or duelsfrequent, those last, in an era of strong political rivalries, when statesmanship tended to walk hand in hand with marksmanship. To discuss all of the states murders that might meet De Quinceys exacting standards would necessitate, not a volume, but an encyclopedia. And so it is contemporary interest which, more than anything else, has dictated the choices for this collection.

I have deliberately omitted several recent cases that excited great public interest and illustrated vividly the night side of human nature. Public inquiry into breaches of the law is, of course, the duty of the police, the courts, and the juries of the state, and the reporting of crimes is a legitimate concern of newspapers. But the historian may be excused if he refrains from noticing crimes of such recent date that their recounting may needlessly wound the feelings of living persons who may have been innocently involved.

The earliest date, then, among crimes presently reported is 1808, and the most recent is 1914. Of all the victimsthey include, among others, a Confederate general, a lovely orphan girl, a pathetic little boy, and a highly offensive political bossperhaps two, and no more, might have survived to this time of writing had their slayers been less pressing with their attentions. Dead, too, are most of the criminals, accusers, witnesses, man-hunters, and others directly concerned. Nobody is apt to suffer agonies of the spirit if reminded of this felony or that.

Four of the murders were committed in North Carolinas piedmont, three in the coastal regions, and three in the mountains, which, be it suggested, sums up to something like geographical impartiality.

As to motivations, it is gratifying to establish that only two men were killed for the sordid purpose of gain. Four were crimes of vengeance, and three were what F. Tennyson Jesse describes as murders of elimination. The tenth murder was for reasons of jealousy, and those reasons were, as the evidence will show, not particularly well founded.

Of those who committed the murders, three were women; and, at risk of seeming to adopt an outworn journalistic convention, it must be recorded that two of these, also two unfortunate feminine victims, possessed exceptional beauty of person. The writer of these essays and his grave advisers are well aware that any woman involved in a major crime, whether actively or passively, is apt to be described as breathlessly lovely. Yet they, and the readers too, must accept the contemporary descriptions of these ladies, which are specific and circumstantial enough. By way of balance, the third murderess was ugly to a surpassing degree, though she was devotedly admired and courted in spite of that, and was publicly compared to the great exemplar of her avocation, Lady Macbeth.

Justice seems to have been plain but moderate in the times when these various tragedies befell and their authors were sought out for punishment. Only three of the ten killers suffered the death penalty, all of them by hanging, all of them in the mountains, and all of them manifestly and inexcusably guilty. Two others escaped the consequences of their deeds by committing suicide. There were three acquittals. One defendant so exonerated was later lynched, and to what extent he deserved lynching the reader may judge for himself. In one case the death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, with later release on parole. One murder, and that perhaps the most cunningly and daringly devised in North Carolinas whole catalogue of violence, was never solved by officers of the law.

Only nine cases, then, came to trial, and the courts dealt with them ably and justly under the state statutes. Of the nine defendants, seven successfully sought change of venue. Six verdicts of guilty were appealed to the State Supreme Court, and for what degree of fairness and intelligence the justices disposed of those appeals the published court records may be consulted.

Since the various cases approximate separate narratives, no effort has been made to offer them in any deliberate order, chronological or otherwise, except where two murders in the mountains showed certain curious similarities that made convenient their inclusion together in a sort of double-barrelled essay.

The facts have not been embroidered with romantic conjecture. Direct quotation, for example, is always from some contemporary account, with, in several instances, indirect quotation made direct by substitution of first person for third. Nor has there been need for embroidery.

For in every instance, the records of the crime and its investigation and trial go far to show us how North Carolinians lived at a certain time and in a certain place. The most obscure person, as slain or slayer, comes to the fixed attention of his fellows, and injuries and trials are singularly vivid in their expositions. The study of a well-documented murder case may tell us as much, perhaps, about those concerned as do the reports of a political campaign or of a marching, fighting army.

In short, these people died, but before they died they lived, and here is an honest effort to prove it.

Manly Wade Wellman

Chapel Hill, North Carolina

May 1, 1954

Contents

DEAD AND GONE

1: The General Dies at Dusk

T HE HOT SATURDAY SUN went down over Old Washington, August 14, 1880. General Bryan Grimes was going home to Grimesland in Pitt County, to his broad white house with its pillared porch and its lofty chimneys and its door that locked with a seven-inch key. Surely that evening he did not think much about his old acquaintance, violent death.

In 1861, when he was a grave-mannered plantation baron of thirty-two, Bryan Grimes had been a member of the convention that voted North Carolina out of the Union and into the Confederacy. Thereafter, Bryan Grimes had joined the Southern army as an infantry major. His regiment had been shot to pieces behind him at Seven Pines450 killed and wounded out of 520. Promoted colonel of the survivors, he recruited them to 327, of whom 250 fell at Chancellorsville. More blood and bullets at Gettysburg, more still in the Wilderness; a brigadier, he survived Sheridans cannonades in the Shenandoah Valley and, a major general, led the last charge of ragged gray infantry on the morning of Appomattox. Then, because he must, he gloweringly accepted the facts and terms of Lees surrender, the furling of the Stars and Bars, the oblivion of the Confederate States of America.