Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2020 by Eric Medlin

All rights reserved

First published 2020

e-book edition 2020

ISBN 978.1.43967.050.7

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020932100

print edition ISBN 978.1.46714.365.3

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

PREFACE

In 1808, the young diarist Edward Hooker traveled through Franklin County and produced one of the first written descriptions of the town of Louisburg. He was not impressed by the towns shabby dwellings or its surrounding barren lands. Hooker had seen too much of Connecticut and the prosperous areas of South Carolina to think highly of what the county had to offer at this early date. However, Hooker was impressed by Matthew Dickinson, the leader of the towns academy, and remarked on the role that transportation might play in the countys future. Hooker noted that the entire county, Louisburg in particular, was in close proximity to the Tar River. He reported the belief of Dickinson and other local citizens that the river was capable of being rendered navigable. A navigable Tar River would connect the county with the much larger town of Tarboro to the east, then to the Atlantic Ocean. This was the only possibility that Hooker observed for the town to eventually grow and become successful.

Fast forward to 2020a much different time for the United States and the worldand the country has a knowledge-based economy, dominated by the internet, service jobs and car travel. With the exception of the Tar River and a few remaining buildings, the county looks nothing like the place Edward Hooker visited; yet, the most recent news story to include Franklin County focused on transportation, specifically the decision to increase funding for the widening of U.S. Route 401 between Louisburg and the bustling state capital of Raleigh. Instead of connecting to Tarboro, the road will connect with Raleigh, which is seen by outside observers as the key to making Franklin County successful.

The story of Franklin County is often one of transportation, geographical relationships and proximity. Franklin County began as a site farther west of most Tuscarora towns and the earliest European settlements. It became the poorer, southern companion of Warren County, sharing a tobacco culture and even some of the same families and plantation home architects. Then, Franklin County was defined by its relationship to Raleigh and other stops on the areas railroads and highways. A plausible story of the countyespecially its towns of Franklinton and Louisburg and its northern plantationsover the past three centuries can be told through these many relationships.

Focusing on the county as a foil for its neighbors, a railway stop or a suburb misses so much of what makes Franklin County unique. A set of unique geographic, social and economic circumstances helped produce a surprisingly advanced and developed rural county. Towns like Louisburg and Franklinton developed their own institutions, including leading centers of education and industry. Architects, artisans and poets created historically significant works of art that must be understood on their own merit. The county produced several political leaders apart from the trends in Warrenton and Raleigh. It is Franklin Countys mix of many influences and its refusal to be defined simply as a tobacco center or as a county of cotton markets and furniture factories that make it such a worthy subject of historical inquiry.

This book deals with Franklin Countys structures, people and role in history, from the pre-European era to the present day. Franklin Countys story is undoubtedly one of success. Franklin County has been one of the wealthiest counties in the state for many years of its existence; it has attracted visits from governors, senators and a plethora of congressmen. Its educational institutions have won accolades and hired national talents. The county has even been able to reinvent itself over the past four decadessince the beginnings of deindustrializationand it seems poised to carry on this level of success like few of its fellow counties in the eastern Piedmont region.

However, a number of people missed out on the countys largesse. A large percentage of the countys residents (in some years, the majority of them) were enslaved for much of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Following Reconstruction, the countys African Americans were subject to discrimination, segregation and acts of political violenceincluding lynching. The countys women and Native Americans also suffered poor treatment. It was not until the later years of the twentieth century that these groups were able to start taking political power and become full citizens of Franklin County. A study of the countys history, even a brief one, must take their experiences into account in order to have any chance of telling the full, rich story that incorporates all of the countys citizens.

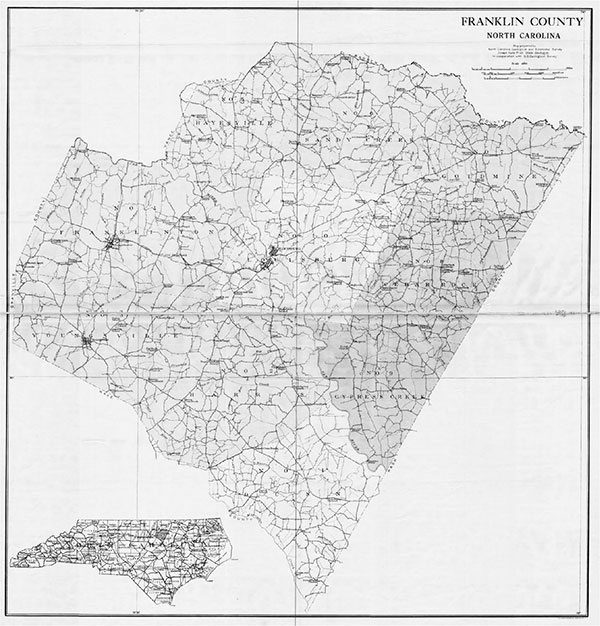

Franklin County map, 1907. Courtesy of the State Archives of North Carolina.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I have many people to thank for the formation of this book. My great thanks go out to the men and women of Franklin County, who helped provide context, information and paths forward for my work. Pat Hinton, Robert Radcliffe, Holt Kornegay and Scott Mumford aided in the research process. Joseph A. Pearce Jr. and Maurice York, two of Franklin Countys most distinguished historians, reviewed my manuscript and provided me with helpful comments and feedback. Vann Evans and Erin Fulp at the North Carolina State Archives, along with Dr. Mary Beth Fitts at the North Carolina Office of State Archaeology, helped me with research, along with the staff at the North Carolina Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. I also received help with images and copyright permissions from the staff members at Our State magazine and the Library of Congress. My special thanks go to Joe Mobley, for giving me the idea to write a county history, and to Michael R. Hill, Michael Coffey and Dr. James Crisp, for guiding my early research. Finally, I would like to thank Susan C. Rodriguez for her extensive help in editing my manuscript at every stage of the process and my mother, Julia Medlin, for inspiring me throughout my life.

BEGINNINGS TO THE REVOLUTION

Franklin County, North Carolina, is located in North Carolinas Piedmont region of rolling hills and fertile soil. The county is the forty-fifth-largest county in North Carolina, containing 491.68 square miles of land and 2.82 square miles of water. Its topography and soil type are typical of most eastern Piedmont counties. The highest point in the countyat 561 feetis located west of the town of Youngsville. The most common type of soil found in the county is Wedowee-Helena; it is a well-draining form of soil, with a loamy surface layer and a subsoil composed mostly of clay. Wedowee-Helena is found primarily in the interior part of the county, along broad ridges and slopes. This soil can grow a number of crops including corn, tobacco, soybeans, sorghum and cotton. Another common soil type in the area, Wake-Wedowee-Wateree, is characterized by its exceptional ability to drain water and its presence on modest slopes. The countys large amount of fertile soil, combined with its few tall ridges and swamplands, have made it a center for agriculture throughout its history.