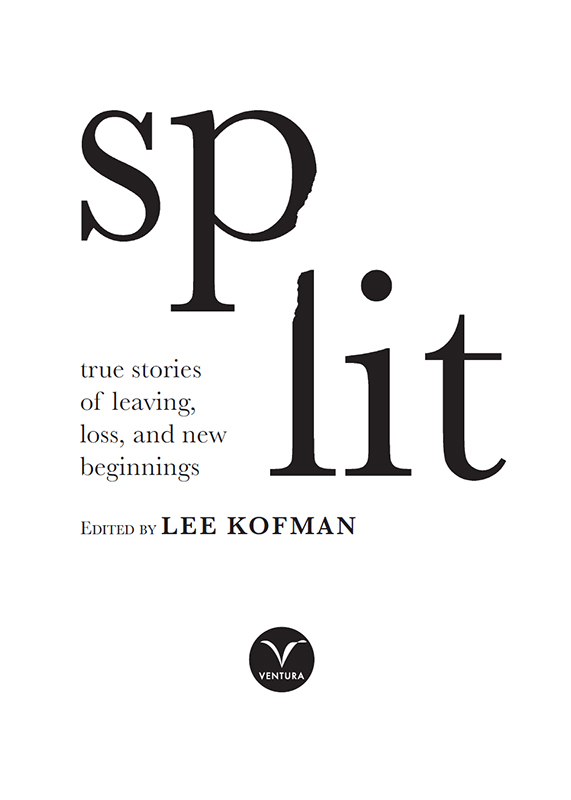

PRAISE FORSPLIT

The emotional range, honesty and deep introspection make Split read like a map of the human heart.

BOOKS + PUBLISHING

How brave these writers are, first to survive the split that seemed impossible, and then to probe their most abject selves. Through their art they mend cracks with gold, illuminate the psychic source of creativity, and give us all courage to change. This is a profound collection, full of surprises, both harrowing and hopeful.

SUSAN WYNDHAM, former literary editor of The Sydney Morning Herald

These diverse tales of leave-takings and ruptures, pain and resilience, heartbreak and healing are unified by their psychological complexity, emotional chiaroscuro and literary brilliance. Each individual story seizes hold of the reader; read together they constitute a fascinating exploration of the fault lines of the human heart.

ALICE NELSON, author of The Childrens House

These writers invite you into their most vulnerable moments and share with you what it means to be human. Split will challenge, entertain and deeply move. I highly recommend.

ELIZA HENRY-JONES, author of P is for Pearl

One day this pain will be useful to you, said Ovid, and this wonderful anthology is all about useful pain.

All these writers have moved on eagerly, reluctantly, or kicking and screaming. Whether they left relationships, employment, family, or the country and culture of their origins, they learned from their pain.

They write about surviving trauma and illness, discovering identity and sexuality, confronting or forgiving their dead. They abandon earlier versions of themselves and at the same time become more themselves.

If you have ever loved and lost, you will recognise these recollections of wisdom hard won, recounted with poise, poignancy, wry humour and occasional joy.

JANE SULLIVAN, author of The Little People

First published in 2019 by Ventura Press

PO Box 780, Edgecliff NSW 2027 Australia

www.venturapress.com.au

Copyright Lee Kofman 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any other information storage retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-925183-87-0 (paperback)

ISBN: 978-1-925183-59-7 (ebook)

Cover design by Design by Committee

Cover illustration by Josh Durham

Internal design by Alissa Dinallo

For Daryl Efron

A story has no beginning or end: arbitrarily one chooses that moment of experience from which to look back or from which to look ahead.

Graham Greene, The End of the Affair

CONTENTS

Graeme Simsion

Virginia Peters

Alice Pung

Gabrielle Lord

Sami Shah

Myfanwy Jones

Peter Bishop

Kerri Sackville

Sunil Badami

A. S. Patric

Hayley Katzen

Lee Kofman

Damon Young

Kate Goldsworthy

Dmetri Kakmi

Ramona Koval

Fiona Wright

Kate Holden

INTRODUCTION

Two years ago, a writers dream came true for me. Jane Curry, the founder of Ventura Press, suggested I edit an anthology of personal essays about endings. Well call it Split, she said.

Split a fissure, a break forcibly into parts, especially into halves or along the grain this is how dictionaries speak of it. An ending that makes you think of wounds, pain, blood, bile; an ending where the stakes are just as high as the suffering endured, even if a certain liberation might ensue. Death, exile, the leaving of a beloved, the passing of youth. The kind of ending from where a lot of great literature begins: Antigone, The Tempest, The Cherry Orchard, Chronicle of a Death Foretold Of course I was game.

To be honest, I was also drawn to the theme to try to settle a score. For a long time now, Ive felt a growing discomfort about the current appetite for a certain type of ending the redemptive kind. In our hyper-therapeutic, ultra-positive times, no matter what tragedy befalls us, no matter how tough the loss might be, the expectation is often that we end things right find closure, overcome adversity, master the art of acceptance, even experience personal growth as a result. I see this discourse everywhere: in online support groups, celebrity interviews, professional advice, everyday conversations.

This comes as no surprise. With environmental and other human-engendered catastrophes never far from our consciousness now, and quasi-dystopian visions becoming a routine part of news reportage, the idea of an unresolved ending rings particularly sinister. And popular culture has always capitalised on the anxieties of its time. Today, on the screen and on the page, we are saturated with so-called inspirational narratives both fictional tales and, even more ubiquitously, real-life stories. Stories of grief, of self-destruction, of hitting the lowest low, of encountering the heart of darkness. Yet in the end their protagonists always emerge into bright sunshine, triumphant and in control of their new circumstances.

I can be a sucker for such stories too. And I think happy endings can be good for us, can render reality more palatable, more manageable. They leave us with hope, and hope has become increasingly hard to get. What bothers me, though, is the certain smug brand of happiness often implied within redemptive stories, where the heroes inevitably become sage through their hardships (and ready to offer their new knowledge to audiences for a suitable price). The impression is that if we can just be astute enough to learn our lessons, then loss always brings wisdom, and this wisdom is whole and perfect and lasts forever after.

Such a spin isnt new, of course. Perhaps it was Saint Augustine who first presented us with this model for narrating troubling personal experiences: Ive sinned, or been through terrible misfortunes through no fault of my own, but eventually I found the right path, and now let me tell you how you can get there too. What is new, or more accurately newer, is the dominion of these narratives in our storytelling landscape. And this bothers me even more.

It is well established by now that, in order to make sense of our lives, we need to both tell and consume stories, continuously. Storytelling matters. It shapes us just as we shape our narratives. A society where redemptive tales predominate has little room for other expressions of human experience doubt, setbacks, unredeemable failures all that stuff that resides at the core of our existence. Such knee-jerk photoshopping of our endings can give rise to unrealistic expectations that once we split from whatever it is that is precious to us we can always get over it, always recover and, even better, improve. But what if we cant? Have we then failed? And should we keep these failures to ourselves, as shameful secrets?

I like happy endings, but I also like the humility, and realness, of narratives about defeats. Or partial defeats. Stories where protagonists might be unable to find the benefit in their splits yet still feel that life is worth living. Or stories where the post-split acquired wisdom is battered, shaky or of the Socrates-kind I know that I know nothing. And what about stories of certain adversities in the face of which it seems immoral to think of ourselves as becoming wiser, because such thinking can diminish their magnitude? In reality, shadowy, messy tales are probably more common than those with a redemptive arc, yet they often remain on the margins of our cultural conversations.

Next page