ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

In preparing any book of this sort, one is always indebted deeply to many people for materials and for encouragement. Although I have done some rewriting in retelling these tales, they remain essentially as they have been known for many centuries in the lands of their origins. Concerning the special stories I have chosen to illustrate the twelve animals of the Asian animal zodiac (all traditional tales from Asian cultures), I am much in the debt of my present publisher, the Charles E. Tuttle Company of Tokyo, for permission to use from their collection of Korean folk legends, The Story Bag (Kim So-Un, ed.), the tale "A Dog Named Fireball."

In preparing any book of this sort, one is always indebted deeply to many people for materials and for encouragement. Although I have done some rewriting in retelling these tales, they remain essentially as they have been known for many centuries in the lands of their origins. Concerning the special stories I have chosen to illustrate the twelve animals of the Asian animal zodiac (all traditional tales from Asian cultures), I am much in the debt of my present publisher, the Charles E. Tuttle Company of Tokyo, for permission to use from their collection of Korean folk legends, The Story Bag (Kim So-Un, ed.), the tale "A Dog Named Fireball."

From the Tuttle Company's Japanese Children's Stories (Florence Sakade, ed.), I have used, with their gracious permission, as well as that of the original translator of the tale, Meredith Weatherby, the ancient Japanese classic, "The Princess and the Herdboy."

From the book Favorite Children's Stories of China and Tibet, compiled by Lotta Carswell Hume and also publised by the Tuttle Company, I have used, with permission, "How the Cock Got His Red Crown," "The Tower That Reached from Earth to Heaven," "How the Here Bested the Wolf," and "How the Deer Lost His Tail."

Among well-known stories from the Japanese classics, I have used "Dojo-ji," a favorite of both the Noh and Kabuki theaters; "The White Hare of Inaba"; and "The Dragon Slayer." From the Kon-jaku Monogatari come the tales "A Monkey Returns a Kindness" (also retold by Hiroshi Naito in Legends of Japan, published by the Charles E. Tuttle Company) and "The Priest and the Monkey Deity."

For the following Korean stories, permission has been received from the London publishers Rout-ledge and Kegan Paul, Ltd.: "The Deer and the Snake," "The Sheep Is Cousin to the Ox," and "The Rat's Bridegroom."

For all the charming animal stories fromVietnam included here, I owe a deep debt of gratitude to my former students at the University of Saigon, who helped me while away long and anxious hours by telling me some of the charming traditional tales of their beautiful land. These include "Why the Tiger Has Dark Stripes," "The Rabbit Bests the Tiger," "The Angel Who Became an Ox," "The Tale of the Tiger and the Mouse," "The Faithful Tiger," and "How the Horse Got His Lovely Big Teeth."

From the book Chinese Fairy Tales and Folk Tales, collected and translated by Wolfram Eberhard, I am indebted to the publishers (Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., Ltd.) for permission to use, with some adaptation, the tales "The Rat and the Ox," "Whence Comes the Ox?" "Titsang P'usa and the Ox," and "Why Does the Cock Eat the Millipede?"

I am grateful also to the Gresham Publishing Company, Ltd., formerly of London, for the stories "The Yellow Dragon" and "The Dog Stone," from Myths of China and Japan, by Donald A. Mackenzie.

Finally, I am most grateful to my husband, Norman Sun, who translated from the Chinese classics, so that I might retell them in English, the stories "The Tailless Rat," "The Old Horse Knows the Way" (as originally written by Han Fei-tzu), "The Lamb Lost on a Branching Road," "The Monkeys and the Chestnuts" (as written by the great sage of the Confucian period, Chuang-tse), "How the Rooster Lost His Horns," "The Pig That Was Too Clever," "Dotting the Dragon's Eye," "The Guardian Snake," and "The Rabbit in the Moon."

For the lines quoted on the dedication page, I am indebted to the Harvard University Press, which gave its kind consent to my use of these lines from the longer poem "East and West" by Ernest Fenollosa, which was delivered as the Phi Beta Kappa poem at Harvard University in 1892.

The New York Times has given its consent to the use of the round diagram called "The Cycle of Twelve," showing the relationship of the twelve zodiac animals to the basic I Ching designs, and centered by the symbolic yin and yang symbols.

From the Julian Press in New York City and Kelly & Walsh Ltd. in Shanghai I have received permission to use the chart, "The Cycle of Sixty," taken from the Encyclopedia of Chinese Symbolism and Art Motives, by C. A. S. Williams.

NOTE (see facing page) : "The Ballad of the Hei Miao" refers to the Black Miao, a hill tribe of Chinese origin. This poem originally appeared in Myths and Legends of China, by E. T. C. Werner (London: George G. Harrap & Co.,1958), p. 406; it is reprinted by kind permission of the publishers. Although this primitive creation legend may originally have been part of the Black Miao's oral tradition, it was first translated, according to the publishers, by Mr. Werner.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ball, Katherine M. Decorative Motifs of Oriental Art . New York: Dodd Mead & Co., 1927.

Blyth, R. H. Oriental Humor. Tokyo: Hokuseido Press, 1959.

Chiba, Reiko. The Japanese Fortune Calendar . Rutland, Vermont, and Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Co., Inc., 1967.

Chavannes, Edouard. "Le cycle Ture des douze animaux." T'oung Pao, series 2, vol. 7. Paris, 1897.

Christie, Anthony. Chinese Mythology . Middlesex, England: Hamlin Publishing Group, Ltd., 1968.

de Bary, William Theodore: Wing-Tsit Chan; and Watson, Burton, eds. Sources of Chinese Tradition . New York: Columbia University Press, 1960.

Dorson, Richard M. Folk Legends of Japan . Rutland, Vermont, and Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Co., Inc., 1962.

Eberhard, Wolfram, trans. Chinese Fairy Tales and Folk Tales. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., Ltd., 1937.

Hume, Lotta Carswell. Favorite Children's Stories from China and Tibet . Rutland, Vermont, and Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Co., Inc., 1962.

Joya, Mock. Things Japanese. Tokyo: Tokyo News Service, Ltd., 1960.

Kim So-un. The Story Bag: A Collection of Korean Folktales. Translated by Setsu Higashi. Rutland, Vermont, and Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Co., Inc., 1955.

Lin Yu-tang. Famous Chinese Short Stories . New York: The John Day Co., 1952.

Lum, Peter. Fabulous Beasts. New York: Pantheon Books, 1951.

Mackenzie, Donald A. Myths of China and Japan . London: The Gresham Publishing Co., Ltd., n.d.

Sakade, Florence, ed. Japanese Children's Stories . Rutland, Vermont, and Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Co., Inc., 1959.

Sun, Ruth Q. Land of Seagull and Fox: Folk Tales of Vietnam. Tokyo: John Weatherhill Co., Inc., 1966.

Volker, T. The Animal in Far Eastern Art . Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1950.

Werner, E. T. C. A Dictionary of Chinese Mythology . New York: The Julian Press, Inc., 1961.

____. Myths and Legends of China . London: George C. Harrap Co., Ltd., 1958.

White, Beatrice. "Medieval Animal Lore," Anglia 72 (1958).

Williams, C. A. S. Encyclopedia of Chinese Symbolism and Art Motives. New York: The Julian Press, Inc., 1960. (Originally published by Kelly & Walsh, Shanghai.)

Yang Hsien-yi and Yang, Gladys, trans. Ancient Chinese Fables. Peking: Foreign Languages Press, 1957.

Zong In-Sob. Folk Tales from Korea . London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, Ltd., 1952.

Yetts, W. P. Symbolism in Chinese Art. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1912.

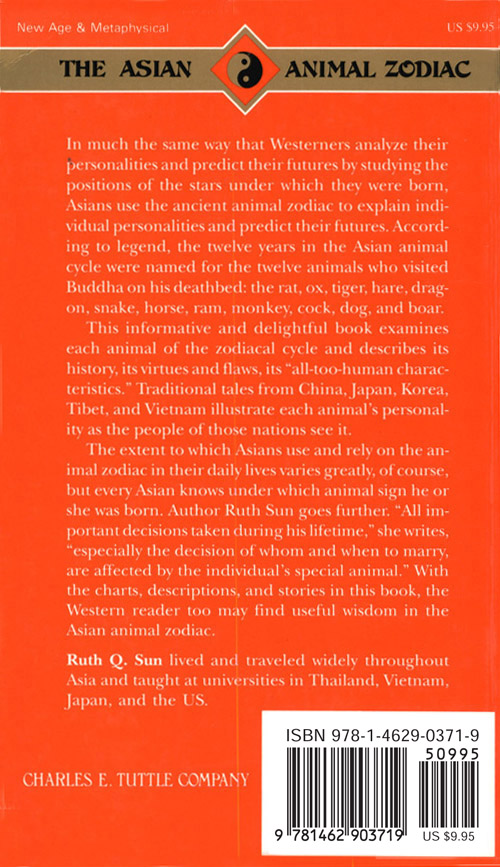

The Rat

Although despised in the West, the rat has traditionally been a highly respected rodent in the Orient. The Chinese thought highly enough of him, in fact, to give him first place in their animal zodiac, where he is declared to represent the beginning of things, or the first cause. According to a popular Buddhist legend, however, the rat earned his lead-off position in the zodiac through typical craftiness and guile. The story goes that when Lord Buddha lay dying, he summoned all the animals to his bedside to say farewell. The faithful ox got a head start and was leading the lengthy procession when the rat, scampering along, caught up to him and begged for a ride on his back. The patient, good-natured ox agreed to this. But when they reached the entrance to the pavilion where Lord Buddha lay, the rat suddenly leaped from the back of the ox and raced inside ahead of him, thereby becoming the first arrival at the bedside. As a reward for such respect, the Buddha honored the rat with the first position in the zodiac.

Although despised in the West, the rat has traditionally been a highly respected rodent in the Orient. The Chinese thought highly enough of him, in fact, to give him first place in their animal zodiac, where he is declared to represent the beginning of things, or the first cause. According to a popular Buddhist legend, however, the rat earned his lead-off position in the zodiac through typical craftiness and guile. The story goes that when Lord Buddha lay dying, he summoned all the animals to his bedside to say farewell. The faithful ox got a head start and was leading the lengthy procession when the rat, scampering along, caught up to him and begged for a ride on his back. The patient, good-natured ox agreed to this. But when they reached the entrance to the pavilion where Lord Buddha lay, the rat suddenly leaped from the back of the ox and raced inside ahead of him, thereby becoming the first arrival at the bedside. As a reward for such respect, the Buddha honored the rat with the first position in the zodiac.

In preparing any book of this sort, one is always indebted deeply to many people for materials and for encouragement. Although I have done some rewriting in retelling these tales, they remain essentially as they have been known for many centuries in the lands of their origins. Concerning the special stories I have chosen to illustrate the twelve animals of the Asian animal zodiac (all traditional tales from Asian cultures), I am much in the debt of my present publisher, the Charles E. Tuttle Company of Tokyo, for permission to use from their collection of Korean folk legends, The Story Bag (Kim So-Un, ed.), the tale "A Dog Named Fireball."

In preparing any book of this sort, one is always indebted deeply to many people for materials and for encouragement. Although I have done some rewriting in retelling these tales, they remain essentially as they have been known for many centuries in the lands of their origins. Concerning the special stories I have chosen to illustrate the twelve animals of the Asian animal zodiac (all traditional tales from Asian cultures), I am much in the debt of my present publisher, the Charles E. Tuttle Company of Tokyo, for permission to use from their collection of Korean folk legends, The Story Bag (Kim So-Un, ed.), the tale "A Dog Named Fireball."

Although despised in the West, the rat has traditionally been a highly respected rodent in the Orient. The Chinese thought highly enough of him, in fact, to give him first place in their animal zodiac, where he is declared to represent the beginning of things, or the first cause. According to a popular Buddhist legend, however, the rat earned his lead-off position in the zodiac through typical craftiness and guile. The story goes that when Lord Buddha lay dying, he summoned all the animals to his bedside to say farewell. The faithful ox got a head start and was leading the lengthy procession when the rat, scampering along, caught up to him and begged for a ride on his back. The patient, good-natured ox agreed to this. But when they reached the entrance to the pavilion where Lord Buddha lay, the rat suddenly leaped from the back of the ox and raced inside ahead of him, thereby becoming the first arrival at the bedside. As a reward for such respect, the Buddha honored the rat with the first position in the zodiac.

Although despised in the West, the rat has traditionally been a highly respected rodent in the Orient. The Chinese thought highly enough of him, in fact, to give him first place in their animal zodiac, where he is declared to represent the beginning of things, or the first cause. According to a popular Buddhist legend, however, the rat earned his lead-off position in the zodiac through typical craftiness and guile. The story goes that when Lord Buddha lay dying, he summoned all the animals to his bedside to say farewell. The faithful ox got a head start and was leading the lengthy procession when the rat, scampering along, caught up to him and begged for a ride on his back. The patient, good-natured ox agreed to this. But when they reached the entrance to the pavilion where Lord Buddha lay, the rat suddenly leaped from the back of the ox and raced inside ahead of him, thereby becoming the first arrival at the bedside. As a reward for such respect, the Buddha honored the rat with the first position in the zodiac.