ACCLAIM FOR

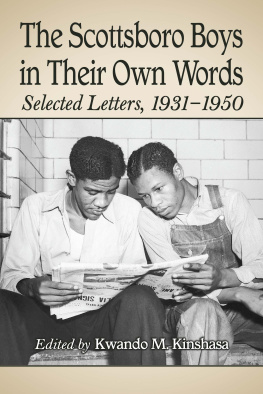

James Goodmans

Stories of Scottsboro

This gripping book does much more than tell the story of Scottsboro with new information and insight. It invents a new way of writing history. Like a kaleidoscope, the author rotates the stories told by various participants in that cause clbre of the 1930s, causing new patterns to emerge until they take a form we can call truth.

James M. McPherson, author of Battle Cry of Freedom

With scrupulous attention to sources Goodman has captured the terror and the agony of the 1930s. A book such as Goodmans goes a long way toward showing how potent history can be, how powerfully it can speak to our own time.

New Republic

This carefully constructed and deeply felt book and the richness of its multiple perspectives makes the Scottsboro case comprehensible as the human event that it was. Goodman has that invaluable attribute of good historians, a sympathetic imagination.

The New Yorker

Its hard to imagine a more complete, or more compelling, version of the Scottsboro events.

Los Angeles Times Book Review

Remarkable and heartbreaking. Artfully weaving his narrative with the voices of dozens of participants Goodman has tackled all of the complexities, shadings and sub-classes of the case.

Boston Globe

James Goodman

Stories of Scottsboro

James Goodman teaches history and social studies at Harvard University. He holds a Ph.D. in American history from Princeton University.

FIRST VINTAGE BOOKS EDITION, APRIL 1995

Copyright1994 by James E. Goodman

All rights reserved under International and Pan American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover by Pantheon Books, New York, in 1994.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Pantheon

edition as follows:

Goodman, James E.

Stories of Scottsboro / James Goodman.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

1. Scottsboro Trial, Scottsboro, Ala., 1931. 2. Trials

(Rape)AlabamaScottsboro. I. Title.

KF224.S34G66 1994

345.76102532-dc20

[347.6102532] 93-5589

eISBN: 978-0-8041-5168-9

v3.1

For Jackson, Samuel, and Jennifer

Contents

Preface

O n March 25, 1931, a fight broke out between a group of white youths and a group of black youths on a freight train traveling through northern Alabama. Black and white alike had been stealing a ride. The black youths got the best of it, and the white youths complained to the nearest stationmaster. A posse stopped the train at the depot in Paint Rock, Alabama, and rounded up nine black teenage boys and two young white women. Someone said something about a rape. Sheriffs deputies arrested the blacks and took them to Scottsboro, the Jackson County seat. A crowd gathered outside the Scottsboro jail. The sheriff called the governor and the governor called out the National Guard. The crowd dispersed. Twelve days later the accused were put on trial for rape, and in four days four separate juries convicted eight of them and sentenced them to death. The Central Committee of the Communist Party of the United States assailed the verdicts, and the Partys legal affiliate, the International Labor Defense, announced that it would defend the boys. Countless people were outraged by the trials and death sentences. Countless others were outraged by the outrage. Appeals led to seven retrials and two landmark Supreme Court decisions. The defendants spent no less than six, and as many as nineteen, years in jail.

What happened? The defendants said they had been convicted of a crime they did not commit: the white boys had attacked them; they hadnt even seen any white women on the train. The women said they had been raped: the Negroes had attacked their companions, thrown them off the train, and then had their way. Communist Party officials said the charge was a frame-up and the trials were a circus, nothing but a legal lynching: the women were prostitutes who had to be coerced to cry rape. Thousands of northerners, white and black, agreed with the Communists and joined them in protesting the convictions. Nearly all black southerners assumed that the boys had been framed. A small group of white southerners concluded that the women had willingly had sex with the boys and cried rape only when they were caught. But most white southerners believed the womens story. They were proud that the citizens of northern Alabama had prevented a lynching and allowed the law to take its course. In all the protest, they saw nothing but the Communists desire to foment race war and revolution. NAACP officials were as critical of the Communists as they were of the verdicts, and fought with the Party for control of the defense.

That was just the beginningthe first few months of a controversy that lasted a decadeand those were only a few of the ways that Americans living in the 1930s understood and explained it. What follows is a history of the court case and controversy, a narrative history in which I move, chapter by chapter, from one point of view to another, until I have recounted the events on that freight train, at the depot in Paint Rock, outside the Scottsboro jail, in and around the Scottsboro courthouse, and all over the country in subsequent years from the perspectives of a wide range of participants and observers. I answer the question What happened? with a story about the conflict between people with different ideas about what happened and different ideas about the causes and meaning of what happeneda story about the conflict between people with different stories of Scottsboro.

I retell peoples stories, and I try to explain them, writing about what people saw and heard, where they got their news and information, and how their memories, ideas, and past experiences shaped their experience of Scottsboro. I show why some people were able to convince others that their stories of Scottsboro were The Story of Scottsboro and why others were not. I show how and why, in response to unfolding events and other peoples stories, some people changed their minds about Scottsboro, how and why, in spite of events and other peoples stories, others did not.

My sources include hundreds of letters written by the defendants; thousands of pages of trial transcripts and other court records; countless newspaper and magazine articles and editorials; the reports of private investigators; letters to newspaper editors and letters to Alabama officials; the manuscript collections of the organizations most interested in the case, including the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching, the Commission on Interracial Cooperation, the American Civil Liberties Union, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the Scottsboro Defense Committee, and the International Labor Defense. My sources include diaries, memoirs, oral histories, and autobiographies; previous histories of Scottsboro and numerous other works of history; Scottsboro songs, speeches, novels, pamphlets, posters, paintings, poems, cartoons, and plays.

I have struggled to be true to my sources. And I have kept myself, as a character, out of my stories, writing each of them from a third-person point of view. But readers should keep in mind that my stories are not transcripts of the stories told in the 1930s, any more than the stories told in the 1930s were transcripts of facts. I decided whose stories to tell and how to tell them. I chose central themes and some of the contexts in which I would like them to be understood. I decided who should have the first word, and who should have the last. I imposed orderat the very least beginnings, middles, and endswhere there was rarely order, created the illusion of stillness, or comprehensible movement, out of the always seamless, often chaotic, flow of consciousness and experience.