Also by KWANDO M. KINSHASA AND FROM MCFARLAND

Emigration vs. Assimilation: The Debate in the African American Press, 18271861 (1988; paperback 2012)

Black Resistance to the Ku Klux Klan in the Wake of Civil War (2006; paperback 2009)

The Man from Scottsboro: Clarence Norris and the Infamous 1931 Alabama Rape Trial, in His Own Words (1997; paperback 2003)

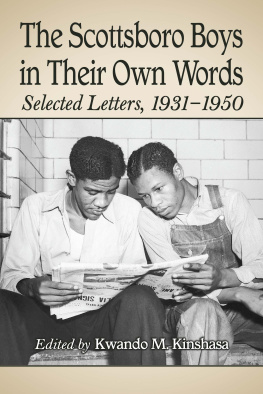

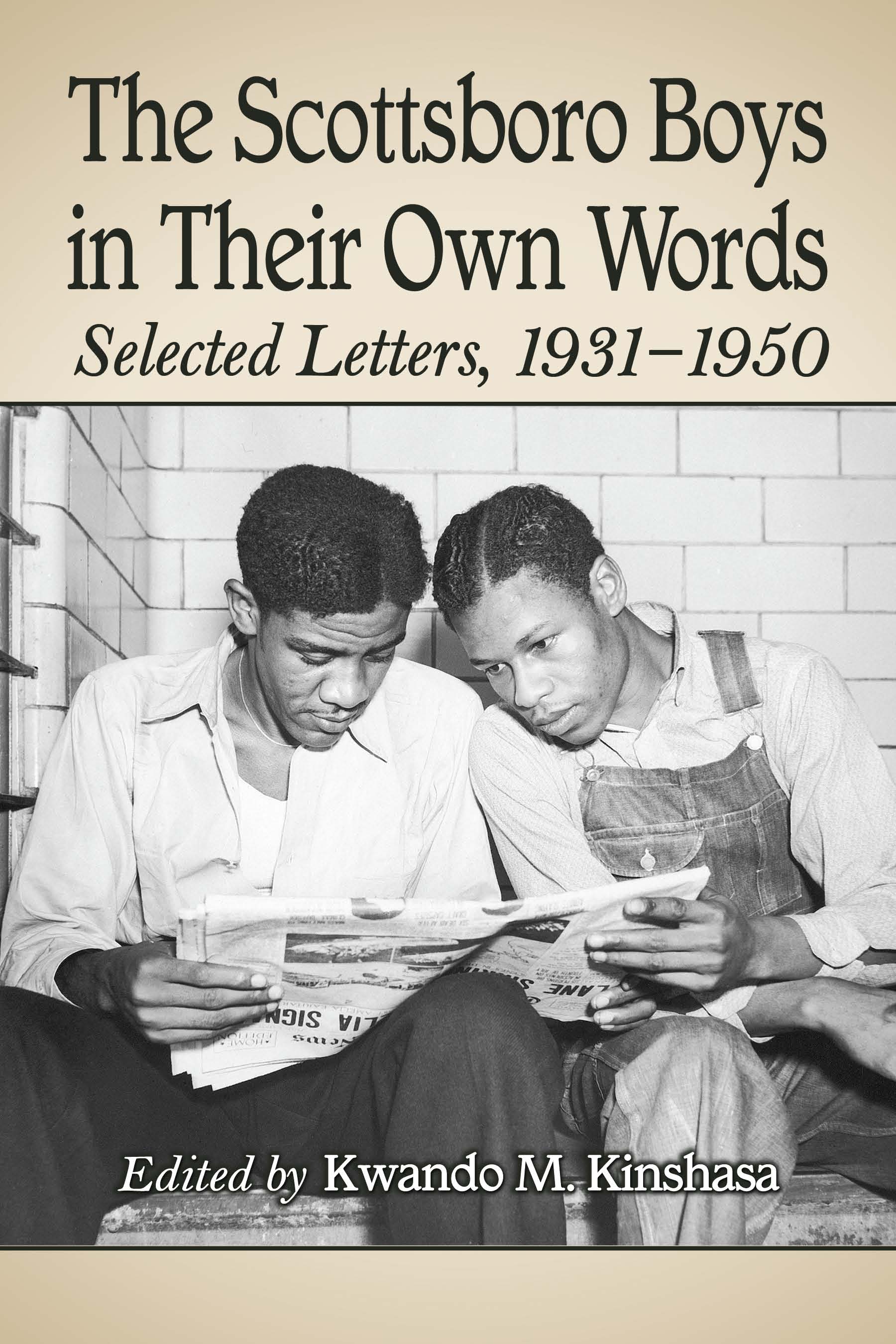

The Scottsboro Boys in Their Own Words

Selected Letters, 19311950

Edited by Kwando M. Kinshasa

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-0344-5

2014 Kwando M. Kinshasa. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Front cover image: Clarence Norris, right, and Charlie Weems, left, in Decatur, Alabama, July 16, 1937 (AP Photo)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

To my wife, Imani Kinshasa,

and her uncompromising sense of justice

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

There are many individuals and institutions who contributed to this publication. However, it was the foresight of a close family friend many years ago, Ms. Willie Mae-Lacy, who put me in contact with a Scottsboro defendant, Clarence Norris, that eventually provided the basis for this volume. In similar fashion, my brief discussion with Attorney Mimi Rosenberg some years ago as to the value of letters written by the Scottsboro defendants is greatly appreciated. An immense appreciation is extended towards Dr. Ira Goldwasser and his wife Harriett Broekman in Amsterdam, who assisted me in researching and translating archival material related to the Scottsboro case written in Dutch at the Internationaal Instituut Voor Sociale Geschiedenis (International Institute for Social History). This material assisted me in better understanding Mrs. Ada Wrights (mother of two of the Scottsboro defendants) visit and presentation to the Dutch Scottsboro Defense Committee in 1933. Special thanks to colleague and scholar Dr. Patricia J. Gibson (John Jay College of Criminal Justice, CUNY) for sharing her thoughts on the relationship between written historical narratives and grammar. I am also extremely thankful for an invitation afforded me by Ms. Sheila Washington to visit the Scottsboro Boys Museum in Scottsboro, Alabama, and for affording me the opportunity to meet with community residents who remembered events surrounding the trials in both Scottsboro and Decatur, Alabama. Special gratitude and respect are expressed to the wisdom and knowledge of the late attorney Joseph Fleming. His awareness of the controversial legal aspects in the Scottsboro case was extremely instructive and insightful, as was his insistence that I get the job done.

I am indebted to the PSC-CUNY Research and Award Program at John Jay College of Criminal Justices Sponsored Research Program Director, Mr. Jacob Marini, and his excellent staff, for providing me the necessary financial support to bring this project to fruition. Without this assistance, conducting my research at archival institutions throughout the nation and abroad would have been difficult at best.

The following universities and archival institutions are acknowledged for their support and providing me with access to both source and contextual material related to the Scottsboro Boys. Specific gratitude is extended to: the Manuscript, Archives and Rare Books Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, the New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations for providing me with the opportunity to examine and include the International Labor Defense Records (Sc Micro R-981). Similarly, I wish to thank the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), for authorizing the use of their correspondence, documentation and image also housed at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture; the Alabama Department of Archival History (ADAH) in Montgomery, Alabama; the Harry Ransom Research Center at the University of Texas in Austin; the Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Dana Collections Scottsboro Boys Trial Collection, 19321938, in the Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library at Emory University (MARBL) in Atlanta, Georgia; the Allan Knight Chalmers Center located in the Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center at Boston University, Massachusetts; the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University, Connecticut; and the Bobst Librarys Tamiment Library archival photo and documentation collection at New York University. A special appreciation goes to Mr. Thomas Mills, Head of Collections at the Cornell University Law Library, New York, for his assistance in providing me with the opportunity to photograph the model freight train used by Attorney Samuel Leibowitz during the 1933 trial in Decatur, Alabama.

I must also acknowledge and honor the support of my parents who when I was a child sat with me at the kitchen table and through countless conversations over many years taught me the importance of the historical narrative. Last, but not least, I thank my family for their understanding and patience while I worked on this project. I salute their concern for my health and the project, and applaud their appreciation of what I do.

PREFACE

Most Americans, particularly those who were black or white, explicitly knew in 1931 that for the foreseeable future their place under an American conception of democracy would be formulated by their race, class and gender, as was that of their fathers father. Ones ancestors were either enslaved, induced to feel that they were members of a suspect race or were valued citizens of a slave-owning society. Implicitly this meant that to challenge the rights of those anointed by social privilege and entitlement in 1931 was to defy tradition and a governing races accepted wisdom on what constituted social order.

Hollace Ransdell, a young teacher, journalist and activist, found this to be the case when, as a reporter for the American Civil Liberties Union, she was sent to the American south and observed the tribulations of Alabamas Scottsboro rape trial. After a few months Ransdell reported, Southern whites feel to their marrow-bone only one thing about the Negro, and they say it over and over. Hundreds of thousands of them have been saying it for generations. They will continue to say it as long as anyone will listen. It is their only answer to the Negro problem. It is their reply to the questions of the Scottsboro casethe Nigger must be kept down (Ransdell, 1931, p. 11).

And just who were these Niggers [who] must be kept down? What was their background? Why were they considered by some to be a threat to the social order, and to others an embarrassment, a problem they would like to whisk away? While an epigrammatic sketch of each defendants background might assist in answering these inquires, as would possibly an understanding of the social context from which they emerged, neither could explicate or illuminate the inner core of each defendants feelings. Only their personal words could assist in that task. However, with this said, the following profiles are helpful in orientating the reader to the minimum that was provided the public in 1931 about each African American youth, soon to be defined as the Scottsboro Boys.

Next page