THE COLLECTED LETTERS OF ROBINSON JEFFERS

with Selected Letters of Una Jeffers

THE COLLECTED LETTERS OF

Robinson Jeffers

WITH SELECTED LETTERS OF

Una Jeffers

VOLUME TWO, 19311939

Edited by James Karman

Stanford University Press

Stanford, California

2011 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press.

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jeffers, Robinson, 1887-1962.

The collected letters of Robinson Jeffers, with selected letters of Una Jeffers / edited by James Karman.

p. cm.

Includes index.

Volune One: ISBN 978-0-8047-6251-9 (cloth : alk. paper)

Volume Two: ISBN 978-0-8047-7703-2 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Jeffers, Robinson, 1887-1962--Correspondence. 2. Jeffers, Una, 1884-1950--Correspondence. 3. Poets, American--20th century--Correspondence. I. Karman, James. II. Jeffers, Una, 1884-1950. III. Title. PS3519.E27Z48 2009

811.52--dc22

2009007528

Adapted from the design by Adrian Wilson for The Collected Poetry of Robinson Jeffers Typeset by Bruce Lundquist in 12/15 Centaur MT

E-book ISBN: 978-0-8047-8172-5

For Paula

love-in-a-mist

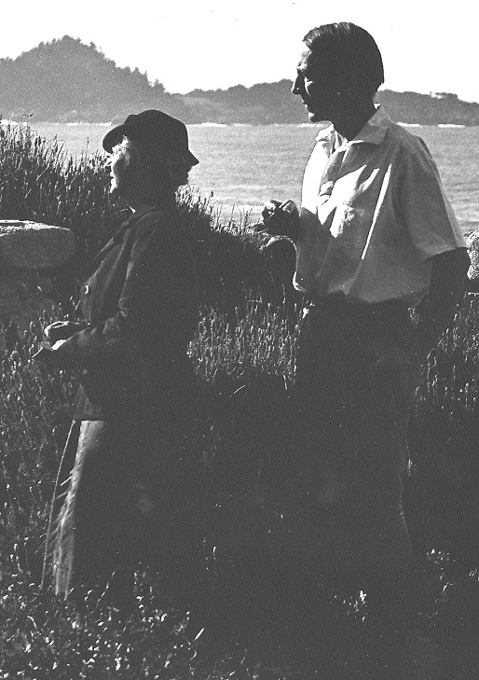

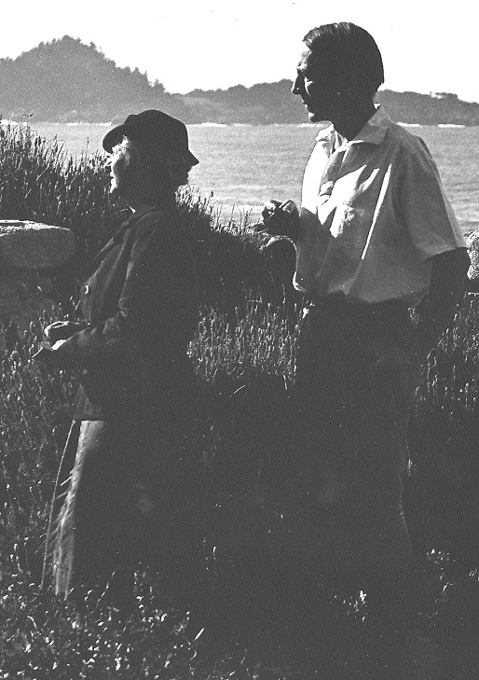

ILLUSTRATIONS

PREFACE

When Robinson and Una Jeffers first committed themselves to a life together, Jeffers hopedpromisedto become a successful poet. I have just three ideas in my head, he tells Una in a letter written December 12, 1912, you are the first:the second is to write as good verse as possible:and the third, to make moneyI mean, plentiful money,in our chosen profession. Reiterating his pledge to meet all three goals, he says I shall keep your love, star-of-hope, till the end of my lifeand yours; I shall write, with you to help me, as good verse as any-ones living now; and, finally, were going to have all the prosperity we shall need. Keep this prophecy, Una-most-beautiful, Jeffers adds with youthful bravado, Ten years from now well read it... and say, How true!

As this passage indicates, Jeffers saw his future career as a joint endeavor. With you to help me, he tells Una, he hoped for success in our chosen profession. At the end of 1928, having achieved international fame with Tamar (1924), Roan Stallion, Tamar and Other Poems (1925), The Women at Point Sur (1927), and Cawdor (1928), Jeffers acknowledged Unas influence. In response to a query about her in a lengthy questionnaire, Jeffers quotes a line by William Wordsworth about his sister Dorothy: She gave me eyes, she gave me ears and arranged my life. Expanding upon this response, Una provides more lines from Wordsworths poem, The Sparrows Nest:

She gave me eyes, she gave me ears;

And humble cares, and delicate fears;

A heart, the fountain of sweet tears;

And love, and thought, and joy.

Una also identifies two traits that, without her influence, might have kept Jeffers from writing steadily: a laisser faire policy about his career and an inveterate rootlessness. By encouraging him to write for a reading public, not just for himself, and by urging him to sink deep roots into the granite coast of Carmel, Una helped Jeffers become the artist he was destined to be. I have great driving force and energy of concentrated effort, Una adds, That has influenced him (Collected Letters 1: 769770, 778).

With Unas help and inspiration, Jeffers career continued to flourish. Dear Judas (1929) was followed by Descent to the Dead (1931), and then Thursos Landing (1932). Interest in the latter book was so great that a photograph of Jeffers by Edward Weston appeared on the cover of the April 4, 1932 issue of Time magazine. The accompanying review and biographical essay cited the widespread opinion that Jeffers was the most impressive poet the U. S. has yet produced. When his publisher, Horace Liveright, filed for bankruptcy in 1933, Jeffers was besieged with contract offers from Americas leading firms. He signed with Bennett Cerf of Random House, who also pursued another prominent Liveright artist, Eugene ONeill. As the 1930s progressed, Jeffers added four new titles to his list of books: Give Your Heart to the Hawks (1933), Solstice (1935), Such Counsels You Gave to Me (1937), and The Selected Poetry of Robinson Jeffers (1938).

Selected Poetry contains a brief foreword in which Jeffers again mentions Unas contribution to his work. After discussing the principles that guided his life as an artist, he identifies the fateful accidents that shaped him. The first of these accidents, he says in an often-quoted passage,

was my meeting with the woman to whom this book is dedicated, and her influence, constant since that time. My nature is cold and undiscriminating; she excited and focused it, gave it eyes and nerves and sympathies. She never saw any of my poems until they were finished and typed, yet by her presence and conversation she has co-authored every one of them. Sometimes I think there must be some value in them, if only for that reason. She is more like a woman in a Scotch ballad, passionate, untamed and rather heroicor like a falconthan like any ordinary person.

In Hungerfield, written late in life, after Una died, Jeffers recalls her last days. You were still beautiful, he says, But notas youd beena falcon. At the end of the poem, he returns to the image. You were more beautiful, he tells Una, Than a hawk flying. And in another late poem, Salvage, Jeffers again declares his Wordsworthian indebtedness to Una, whose eyes made life. As for me, he says, reflecting on his passive and her active personality, I have to consider and take thought / Before I can feel the beautiful secret / In places and stars and stones, to her it came freely.

Jeffers cold and undiscriminating nature, his need to consider and take thought, were part of what he regarded as a granite-like temperamentone that could shed pleasure and pain like hailstones (Soliloquy) and endure the vicissitudes of existence with stoic indifference. At the same time, however, he associated the artistic side of his life with raptors. In a late poem about his ongoing search for poetic subject matter, he refers to himself as an old half blinded hawk hunting for prey. By referring to Una as a hawk as well, Jeffers identified her as the feminine embodiment of his own creative spiritand thus, in psychological terms, his anima ideal. The balance he experienced, and depended upon, between himself and Una finds an echo in Rock and Hawk, a poem written in the mid-1930s. Seeing a lone hawk perched upon a headland stone, Jeffers notes the conjunction of bright power and dark peace, of fierce consciousness with final disinterestedness. Together, Jeffers says, the two ways of being create an image of integrated awareness, with the falcons / Realist eyes and act / Married to the massive / Mysticism of stone.

Just as Jeffers poetry resulted from the interpenetration of these two modes of existence, his life worked best when theyand when he and Unawere in balance. In the 1930s, however, balance was difficult to achieve. Several factors disrupted Jeffers equilibrium, with increasing force as the decade wore on.

Next page