The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2021 by Nicholas L. Syrett

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2021

Printed in the United States of America

30 29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-63874-4 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-76155-8 (paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-75166-5 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226751665.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Syrett, Nicholas L., author.

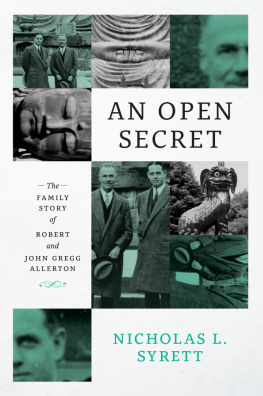

Title: An open secret : the family story of Robert & John Gregg Allerton / Nicholas L. Syrett.

Description: Chicago : The University of Chicago Press, 2021. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020036091 | ISBN 9780226638744 (cloth) | ISBN 9780226761558 (paperback) | ISBN 9780226751665 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Allerton, Robert, 18731964. | Allerton, John Gregg, 18991986. | Gay menIllinoisBiography. | PhilanthropistsIllinoisBiography. | Gay couplesIllinois. | Gay adoptionIllinois.

Classification: LCC HQ 76.35.U6 S97 2021 | DDC 306.76/620922 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020036091

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Allerton Family at The Folly

Richest Bachelor in Chicago

Allerton House

Chinese Maze Garden

Fu Dog

The Man in Black by Glyn Philpot

Robert Allerton in Tahiti

John Gregg

Katherine, John, and Scranton Gregg

A garden room at Lawai-Kai

Map of Allerton Properties on Kauai

Unpacking the Sun Singer

Picnicking at Lawai-Kai

Gregg and Allerton in Hamburg

Allerton and Gregg at the Great Buddha of Kamakura

John Wyatt Gregg Allerton name-change announcement

On March 4, 1960, Robert Allerton became a father. He was eighty-six years old at the time and his newly adopted son, John Gregg, was sixty. The pair had already been living together and calling themselves father and son for almost four decades. Thus, the adoption, while legally affirming Allerton and Greggs filial status, paradoxically had the effect of bringing that very status into question. Allerton was an immensely wealthy benefactor of the arts, both in Illinoiswhere he and Gregg maintained legal residence and where the adoption took place, the first adoption of an adult child in the states historyand in Hawaii, where the two had lived for twenty years. The adoption was newsworthy in both places. The Champaign-Urbana Courier, covering the jurisdiction where the adoption was finalized, announced: Companion Is Adopted by R. Allerton. Other papers used similar sorts of headlines: Robert Allerton Adopts Friend. Robert Allerton, Piatt Park Donor, Adopts Companion of Many Years. Even more ambiguously the Honolulu Star-Bulletin titled its article Have Been Friends for 38 Years. Kauais Allerton, 86, to Adopt 60-Year-Old Son, referring to Gregg as both a friend and a son before the adoption had even occurred. The reporter explained that Mr. Allerton and Mr. Gregg have lived at Lawai-Kai on Kauai since 1938 and many friends believed that Gregg already was Allertons adopted son.

Despite the fact that the adoption did make them father and son in the eyes of the law, it also had the public effect of calling into question the very thing it was most designed to assert: that Robert Allerton was John Greggs father, and not something else. And yet, as the Star-Bulletin noted, perhaps despite itself, it is difficult to become something that one claims already to be. In a similar vein, the Chicago Tribune reported that Gregg had had the status of son for thirty years under the headline Son 30 Years Is Adopted by Allerton, the quotation marks around son suggesting doubt about Greggs real status over those decades. This conundrumwho Robert Allerton and John Gregg were to each other and how they explained themselves to the worldhad been, in many respects, the fundamental question of their then thirty-eight years together.

This book tells the story of their lives. Born in the late nineteenth century to one of Chicagos richest entrepreneurs and raised among its elite, Robert Allerton was expected by most around him to assume the responsibilities of his fathers business, marry an eligible young Chicago socialite, and produce the next generation of Allertons. In one respecttaking on some of his fathers business interestshe did so, but he also engaged in socializing at home and abroad with a cosmopolitan jet set that included artists, musicians, and socialites, gay men among them. He had at least one affair with a man, the British composer Roger Quilter; there were likely others. And in 1922, nearing the age of fifty, he met a college student named John Gregg, twenty-six years his junior. From that day forward, they were rarely apart, splitting their time between an English manor house in downstate Illinois and a tropical paradise on the southern shore of Kauai in Hawaii. They referred to one another as father and son from the 1920s until the death of John Gregg in 1986, securing that status in the law in 1960.

Robert Allerton and John Gregg were a handsome and popular pair. Well-read and worldly, they entertained frequently and traveled the globe with their friends. They also dedicated themselvesboth in their own homes and through generous philanthropyto the arts, focusing in particular on architecture, landscape design, and decoration. Allertons employees describe a generous man who looked after the needs of those who worked for him. Their letters show a keen sense of humor as well as exacting temperaments; Allerton, in particular, had precise ideas of how he wanted things done, and his wealth meant that he did not often have to compromise. They were both also quite private, Allerton even more so than Gregg. While Allertons wealth meant that he was often the subject of media coverage, he rarely agreed to be photographed or give interviews. Allertons choice to live away from Chicago in rural Piatt County, Illinois, also indicates that as much as he liked to socialize, he was not at all opposed to living in solitude with his books and his dogs. In sum, Allertons wealth, which he came to share with Gregg, allowed him to set the terms on which he engaged with the rest of the world. Deciding when to be private and when to have company were two facets of this privilege; calling John Gregg his son and having the world acquiesce to those terms, even if they were not quite believable, was another.

The years of Robert Allertons life, 18731964, encompass an almost-century-long arc during which homosexuality in American culture was first discovered, diagnosed, pathologized, and persecuted. By the time of his death, those named by the category had begun to assert their own rights. If we include John Greggs final yearshe lived until 1986this century also encompasses the birth of gay liberation and the beginnings of the AIDS crisis. Because of this, it is possible to see how one man, eventually joined by another, negotiated changing understandings of same-sex sexuality in America (and, at times, in Europe and Asia). In some ways, Allerton typifies what we have come to know about the history of same-sex intimacy in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. From his earliest days, for instance, he was involved in a romantic friendship with a childhood companion, the painter Frederic Clay Bartlett. The intensity of that friendship ended, however, when Bartlett married. Allerton then met a series of queer men while traveling in Europe and elsewhere. He had an affair with at least one of them, and with others practiced a sort of queer mentoring that had long been popular among gay men in Europe. Finally, looking to settle down more permanently with only one man by the 1920s, he met John Gregg. It was at this moment that Robert Allertons story becomes unique and anomalous, though revealing about queer history, nevertheless.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).