Introduction

GREGG MITMAN AND KELLEY WILDER

But the introduction first of photography and subsequently of film in documenting the present created new types of records that altered notions of historical, legal, and scientific evidence; changed interactions among scientists and their subjects; and challenged the very construction and meaning of the archive.

The documentary impulse that emerged in the late nineteenth century combined the power of science and industry with a particularly utopian (and often imperialistic) belief in the capacity of photography and film to visually capture the world, order it, and render it useful for future generations. The unifying sense of purpose, evident in early manifestos like The Camera as Historian, which encouraged the scientific use of photography and film in documenting projects of truly enormous scope, is perhaps now less visible, buried amid the staggering quantity of photographs and films that such projects generated..

In the virtual world of images summoned by every scholarly query, we tend to forget the material dimensions of the visual. But the sheer mass of photograph and film documents that take up space in archives and consume vast resources in their virtual state on the web is a reminder that the materiality of photographs and films extends far beyond the chemistry, size, and format of a particular document. At 100 million images and counting, Corbis, for example, one of the largest sites for one-stop shopping for digital still and moving images, is dependent upon a gigantic physical infrastructure of fiber optic cables, routers, hubs, and servers that greatly expand the material footprint of the archival image. It is merely the tip of an iceberg, amassed over a century of collecting via photography and film. Whether we measure in quantities of acid-free solander boxes and meters of rolling stack shelving or by the electricity powering countless servers delivering the public interface of museums and galleries, online databases and image banks, it is clear that acquisition and storage far outstrip chemistry, size, and format as material aspects of the documentary impulse. Stopping at acquisition and storage would also only give an incomplete picture of the effect of this impulse. Each step of documentationfrom the initial recording of images, to their acquisition and storage, to their circulationhas physically transformed natural and built environments, altered the lives of human subjects, reconstituted disciplines of knowledge, and changed economic and social relationships.

This book is about the material and social life of photographs and films made in the scientific quest to document the world. We find their material and social traces in the impulse that drove their creation; the historical and disciplinary dynamics that surrounded their production; the collecting practices of librarians, archivists, and corporations; and the archives they inhabit. Together, the essays in this volume call into question the canonical qualities of the authored, the singular, and the valuable image, and transgress the divides separating the still photograph and the moving image, as well as the analogue and the digital. They also overturn the traditional role of photographs and films in historical studies as passive illustrations in contrast to active textual scholarship.

In the last decade, photographic and film scholars like Gillian Rose, Joan Schwartz, Paula Amad, Elizabeth Edwards, and others have taken seriously the notion that questions of materiality and agency lie at the heart of photographic documentation.). Meaning and fact lie not simply inside the photographic material but in a set of relationships formed between the maker, the user, the object, and the archive.

Drawing upon scholars from across the fields of art history, visual anthropology, and science and technology studies, Documenting the World interrogates questions of materiality and agency in the work that photographs and films do as evidentiary documents, narrative objects, and the stuff of archives. Despite the authors different disciplinary backgrounds, the essays share a commitment to make tangible the different material manifestations of photographs and films: in the making of the document as evidence (Tucker, Edwards, Geimer, Vertesi); in the narratives accompanying the circulation and recirculation of still and moving images (Edwards, Mitman, Ginsburg); and in the life of photographs and films within the archive (Klamm, Wilder, Blaschke).

These themesdocuments and evidence, circulation and recirculation, and archival livesoffer a general structure to the volume. We open with acts of becoming, as photographs and films acquire evidentiary force in the world. The essays span more than a century, from the place of photographs and films ), for example, Peter Geimer asks the provocative question, How could it be that throughout the nineteenth century photographs were treated as documents, visual evidence, and traces of the real even though such a fundamental dimension of realitycolorwas missing? Photography and film have mattered literally, as Geimer shows, in imaginings of the past as a monochromatic world of black and white.

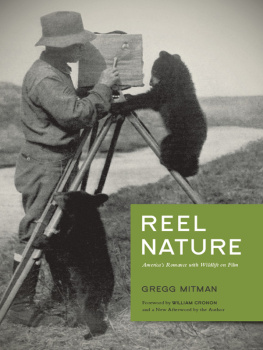

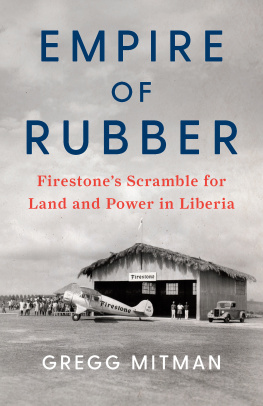

But what happens when the material and social relations of the documentary object are reconstituted, resulting in quite different stories and political ends from those initially intended in their making? In Gregg Mitmans investigative journey into the many lives of a 1926 Harvard expedition film shot in Liberia ( In these liberating acts, photographs and films are literally reborn through new social relations.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).