PRAISE FOR HOW TO SEE THE WORLD

Traveling to the moon and back, across continents and between eras, Mirzoeff nimbly and effectively narrates the visual regimes that regulate what we see, how we see, and what remains completely hidden from view. Indispensable reading for the twenty-first century.

Jack Halberstam, Professor of American Studies and Ethnicity, Gender Studies, and Comparative Literature, University of Southern California and author of The Queer Art of Failure

This book will transform the way you see the worldand how you want to change it. Eloquently written, it offers new insights on everything from selfies as a new global art form to impressionist art as evidence of global climate change. It is simply brilliant.

Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, Professor and Chair, Modern Culture and Media, Brown University

Nicholas Mirzoeff connects images and practices of looking to political struggles, up to and including the survival of the planet. In clear, powerful prose, Mirzoeff shows how visuality is at the very center of struggles for social justice, at moments of both domination and resistance. An essential introduction for anyone who wants to understand visuality today.

Jonathan Sterne, James McGill Professor in Culture and Technology, McGill University and author of MP3: The Meaning of a Format

A lucid and accessible introduction to how images shape our lives and effect change, political and social... [How to See the World] offers numerous insights into reading the significance of images in the world today and is filled with intriguing, insightful nuggets. A challenging and provocative inquiry into how we see the world.

Kirkus Reviews

Beautifully written, with a broad sweep of examples that speak to the power of images and encourage us to see and think in new ways, How to See the World is the go-to book for scholars and students in fields ranging from political science and anthropology to art history.

Suzanne Blier, Allen Whitehill Clowes Chair of Fine Arts and of African and African American Studies, Harvard University

Also by Nicholas Mirzoeff:

An Introduction to Visual Culture

The Visual Culture Reader

The Right to Look

Copyright 2016 by Nicholas Mirzoeff.

Published by Basic Books,

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

First published in the United Kingdom by Pelican Books, an imprint of Penguin Books. Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, contact Basic Books, 250 West 57th Street, New York, NY 10107.

Books published by Basic Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

Designed by Jack Lenzo

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015956107

ISBN: 978-0-465-09601-5 (e-book)

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Kathleen, as ever

Table of Contents

Guide

CONTENTS

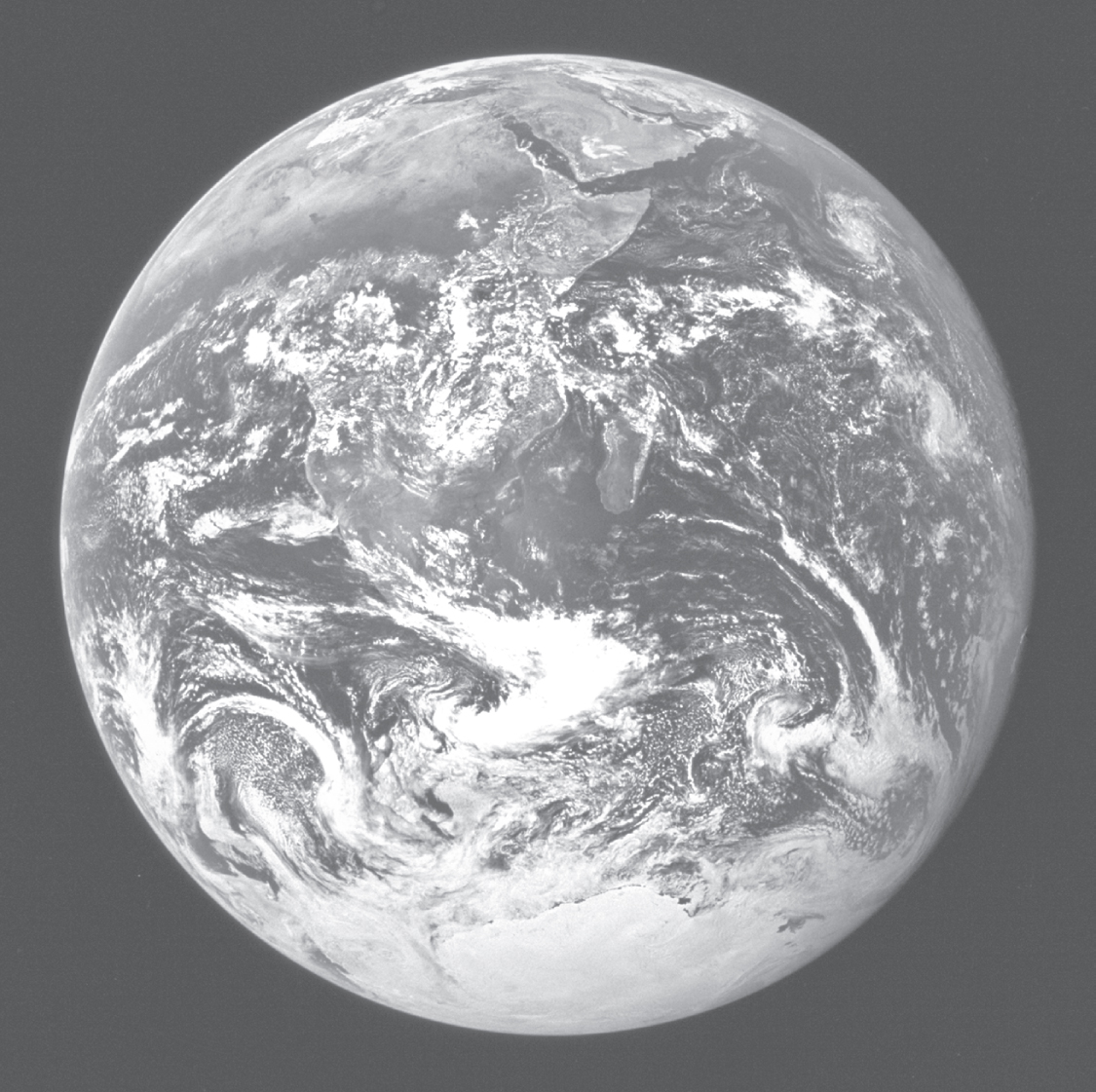

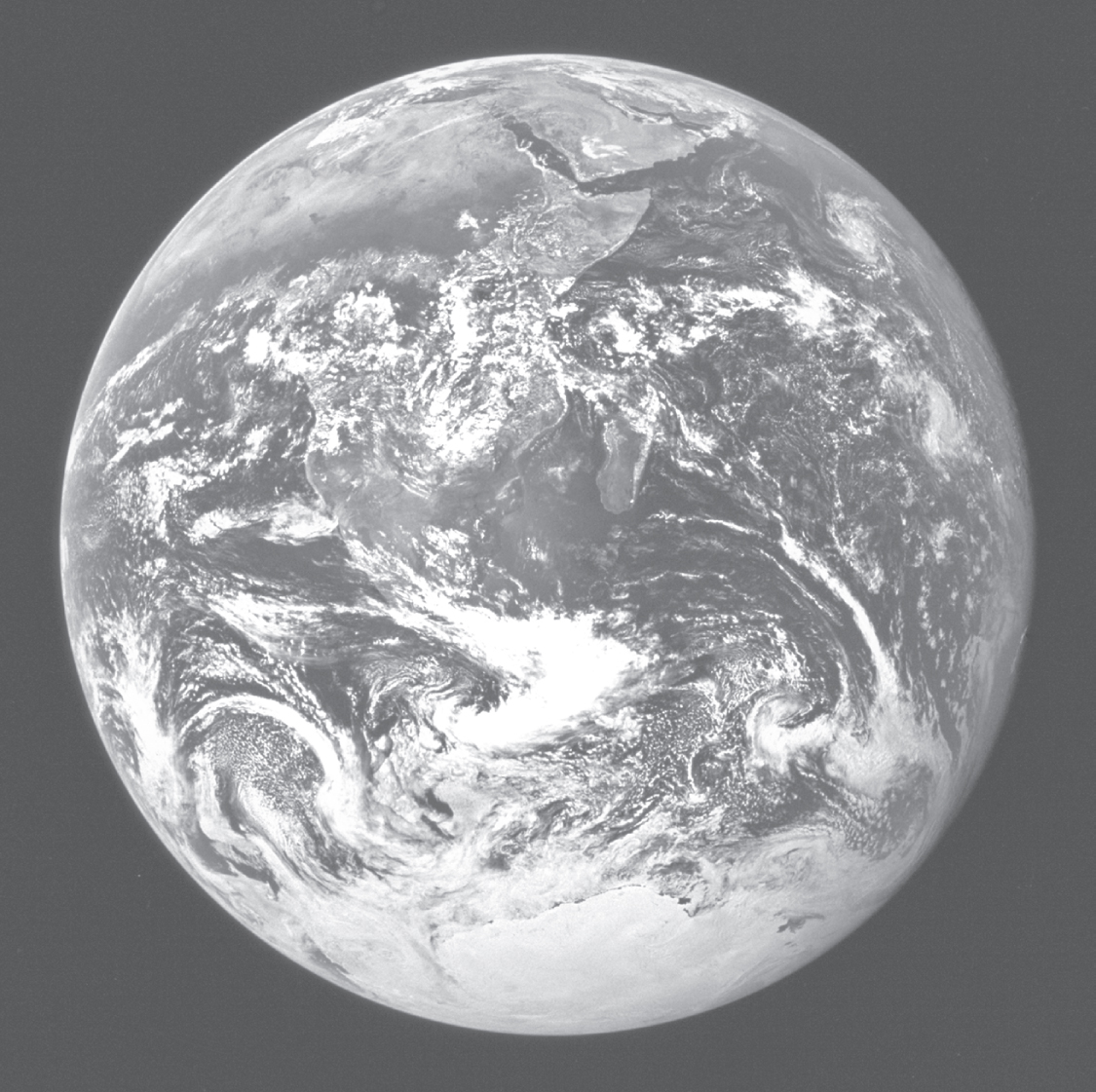

I n 1972, the astronaut Jack Schmitt took a picture of Earth from the Apollo 17 spacecraft, which is now believed to be the most reproduced photograph ever. Because it showed the spherical globe dominated by blue oceans with intervening green landmasses and swirling clouds, the image came to be known as Blue Marble.

The photograph powerfully depicted the planet as a whole, and from space: no human activity or presence was visible. It appeared on almost every newspaper front page around the world.

In the photograph, Earth is viewed very close to the edge of the frame. It dominates the picture and overwhelms our senses. Since the spacecraft had the sun behind it, the photograph was unique in showing the planet fully illuminated. The Earth seems at once immense and knowable. Taught to recognize the outline of the continents, viewers could now see how these apparently abstract shapes were a lived and living whole. The photograph mixed the known and the new in a visual format that made it comprehensible and beautiful.

At the time it was published, many people believed that seeing Blue Marble changed their lives. The poet Archibald MacLeish recalled that for the first time people saw the Earth as a whole, whole and round and beautiful and small. Some found spiritual and environmental lessons in viewing the planet as if from the place of a god. Writer Robert Poole called Blue Marble a photographic manifesto for global justice (Wuebbles 2012). It inspired utopian thoughts of a world government, perhaps even a single global language, epitomized by its use on the front cover of The Whole Earth Catalog, the classic book of the counterculture. Above all, it seemed to show that the world was a single, unified place. As Apollo astronaut Russell (Rusty) Schweickart put it, the image conveys

the thing is a whole, the Earth is a whole, and its so beautiful. You wish you could take a person in each hand, one from each side in the various conflicts, and say, Look. Look at it from this perspective. Look at that. Whats important?

No human has seen that perspective in person since the photograph was taken, yet most of us feel we know how the Earth looks because of Blue Marble.

That unified world, visible from one spot, often seems out of reach now. In the forty years since Blue Marble, the world has changed dramatically in four key registers. Today, the world is young, urban, wired, and hot. Each of these indicators has passed a crucial threshold since 2008. In that year, more people lived in cities than the countryside for the first time in history. Consider the emerging world power Brazil. In 1960, only a third of its people lived in cities. By 1972, when Blue Marble was taken, the urban population had already passed 50 percent. Today, 85 percent of Brazilians live in cities, no less than 166 million people.

Most of them are young, which is the next indicator. By 2011, more than half the worlds population was under thirty; 62 percent of Brazilians are twenty-nine or younger. More than half of the 1.2 billion Indians are under twenty-five, and a similar young majority exists in China. Two thirds of South Africas population is under thirty-five. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, 52 percent of the 18 million people in Niger are under fifteen and in most of sub-Saharan Africa, over 40 percent of the population is under fifteen. The populations of North America, Western Europe, and Japan may be aging, but the global pattern is clear.

The third threshold is connectivity. In 2015, 45 percent of the worlds population had some kind of access to the Internet, up 806 percent since 2000. Its not just Europe and America that are connected: 45 percent of those with Internet access are in Asia. Nonetheless, the major regions that lack connection are sub-Saharan Africa (other than South Africa) and the Indian subcontinent, creating a digital divide on a global level. By the end of 2014, an estimated 3 billion people were online. By the end of the decade, Google envisages 5 billion people on the Internet. This is not just another form of mass media. It is the first universal medium.