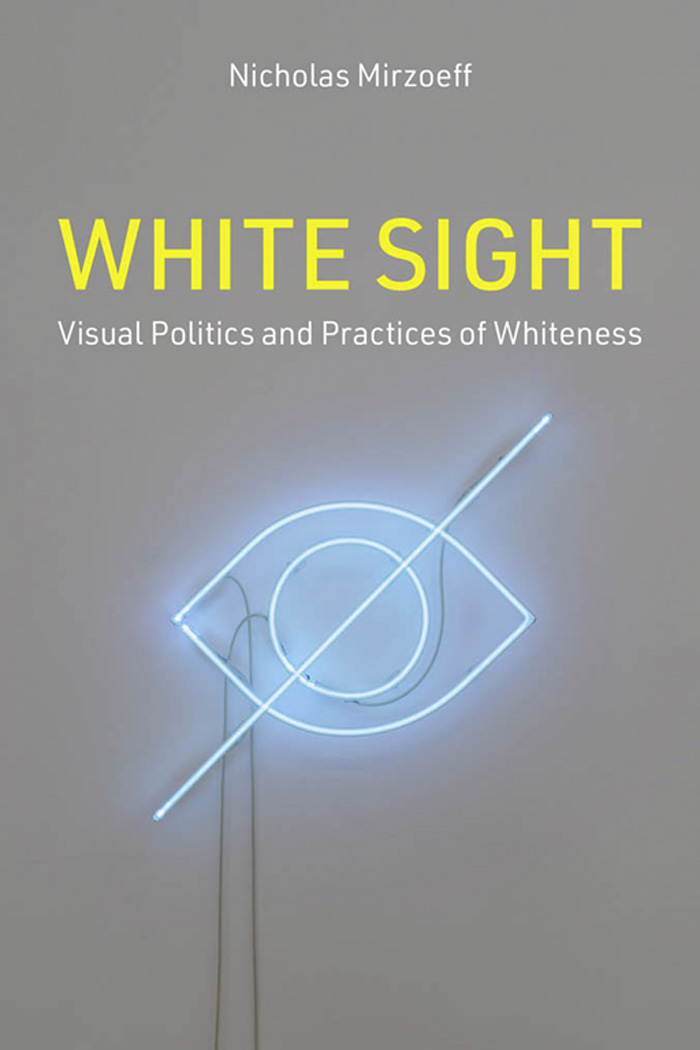

White Sight

White Sight

Visual Politics and Practices of Whiteness

Nicholas Mirzoeff

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2023 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

The MIT Press would like to thank the anonymous peer reviewers who provided comments on drafts of this book. The generous work of academic experts is essential for establishing the authority and quality of our publications. We acknowledge with gratitude the contributions of these otherwise uncredited readers.

This book was set in Arnhem Pro and Frank New by New Best-set Typesetters Ltd.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Mirzoeff, Nicholas, 1962 author.

Title: White sight : visual politics and practices of whiteness / Nicholas Mirzoeff.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The MIT Press, [2023] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022009613 (print) | LCCN 2022009614 (ebook) | ISBN 9780262047678 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780262373098 (epub) | ISBN 9780262373104 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH: White peopleRace identity | White nationalism. | Slavery. | Visual communication.

Classification: LCC HT1575 .M57 2023 (print) | LCC HT1575 (ebook) | DDC 305.8dc23/eng/20220429

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022009613

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022009614

10987654321

d_r0

Contents

Acknowledged

My work here must begin by acknowledging who I am. I acknowledge my own complicities and engagements, disavowals and refusals of and with whiteness and white masculinity. To begin at the beginning, I acknowledge being a person clearly identified as white in the United States. In the United Kingdom where I grew up, I was identified as not-Black but not fully English. My last name and being visibly Jewish disqualified me at once. This particularly English situation is one that Black British scholar Hazel Carby calls The Question! If whiteness is a place, this book is my response to that question.

In the United States, almost all the operations of the color line in the settler colony remain active, and I acknowledge that I have, like it or not, benefited from its privileges. No one needs to remind me that I am far from perfect in this or any other regard. Its not about me, though. Its about the kind of we that we want to be. I acknowledge writing to you from Lenapehoking, the ancestral lands of the Lenape people, who have been for the most part expelled from the region, even though New York City still has the largest urban Indian population in the country. What is now Washington Square, where I live and work, was also part of an area known as Land of the Blacks under the Dutch. A small group of Africans were designated as half free on condition that they grew food for the nascent settler community. The land that they farmed is buried today beneath a thirty-foot layer of soil, comprised of ballast from transatlantic shipping.

To acknowledge beginning from this kind of ground is to think in layers, or as geologists put it, stratigraphically. Art historian Sarah Elizabeth Lewis resonantly calls it groundwork. The mask is not the skin, given that Fanon specified Black skin as its counterpart. Nor is it the face. It is a set of assumptions, concepts, infrastructures, learned experiences, symbols, and techniques that form a screen by which a person makes white reality. The point of the mask is to keep whitenesss dominance invisibilized. As a central figure in what Cedric J. Robinson named the Black radical tradition, Fanons insights have resonated with me, not least for his persistent engagement with Jews (see especially chapter 6).

Throughout this book, Ive learned from the Black radical tradition, from James Baldwin, Angela Y. Davis, and C. L. R. James, to Robinson himself, how to think white sight. Legal scholar Joanne Barker points out how laws regulating Indigenous status and rights are central in defining the conditions of power for those classified as white. Whiteness cannot be understood without thinking at those intersections and with this learning. My work here situates my own ambivalent placing within that whiteness as a person in Jewish diaspora whose very body is the product of empire, primarily in relation to the Indigenous and Black radical traditions in the Atlantic world. I acknowledge that this framing is all incomplete, while also bearing the knowledge that no one person or book can be adequate to the task.

I acknowledge learning in particular from these traditions about the use of visual materials in discussing the making of whiteness. Placing racist imagery in circulation yet again in order to criticize it is not going to make the change I want to see and perpetuates harm. It is more important to keep the focus on making whiteness on and around white bodies than to once again share racist caricatures of Africans. To that end, I have sometimes redacted racist imagery and often not reproduced it. For example, I chose not to reproduce J. T. Zealys daguerreotypes (chapter 2) while Tamara Laniers court case for the restitution of the depictions of her ancestors Renty and Delia Taylor was underway. By the same token, I have used activist images rather than the work of photojournalists wherever possible (unless the photo is itself the story) because visual activism frames the world in different ways.

Far from marking a new moment in human history, the financial globalization known as neoliberalism that was brought to a halt by the COVID-19 pandemic was another inflection within this long history of colonization. Everything from biometrics to drones and the era of big data has recently been understood as part of the five-centuries-long structure of European racializing, settler slavery, and settler colonialism. What remains to be done, as it has since 1492, the mythical origin of that project, is to finally decolonize.

Nowhere has this been more the case than with whiteness. The five years during which I worked on this book were constituted by repeated shocks known as Trump, Brexit, and Bolsonaro (to mention just three), marking the resurgence of what had, perhaps optimistically, been thought to be a past moment of overt white supremacy. When I presented my work around the Black Lives Matter movement at colleges and universities in 2016, it was uncomfortably obvious that the audience was almost entirely white.

When I watched with appalled amazement the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, around the statue of Confederate general Robert E. Lee, leading to the murder of counterprotester Heather Heyer, it became horrifyingly clear that as well as this scholarship had been done, there was now more to do. In his 1997 classic White, Dyer urged his readers that it is important to come to see whiteness. I am working in the wake of this changing tradition.

I had worked on monuments, museums, public art, and statues in the 1990s and early 2000s at the beginning of formulating what became visual culture, a now-commonplace but once controversial formula. In 2017, it became clear that whiteness was deeply connected to everything that visual culture might be. My task was to learn how to use the new ideas about whiteness in this dramatically changed context. Of course, in thinking about making whiteness in the visual field, I come in the wake of manyperhaps first the many Bergers: John Berger, the lamented Maurice Berger, and Martin Berger. And yet the context is worryingly different. The general crisis of whiteness that became visible in 2016 accelerated to the point of insurrection in 2021. I acknowledge, finally, that the whiteness discussed in this book is always concerned with the long formation of this crisis, meaning that there are many other optics I am aware have not been covered in one short book.

Next page