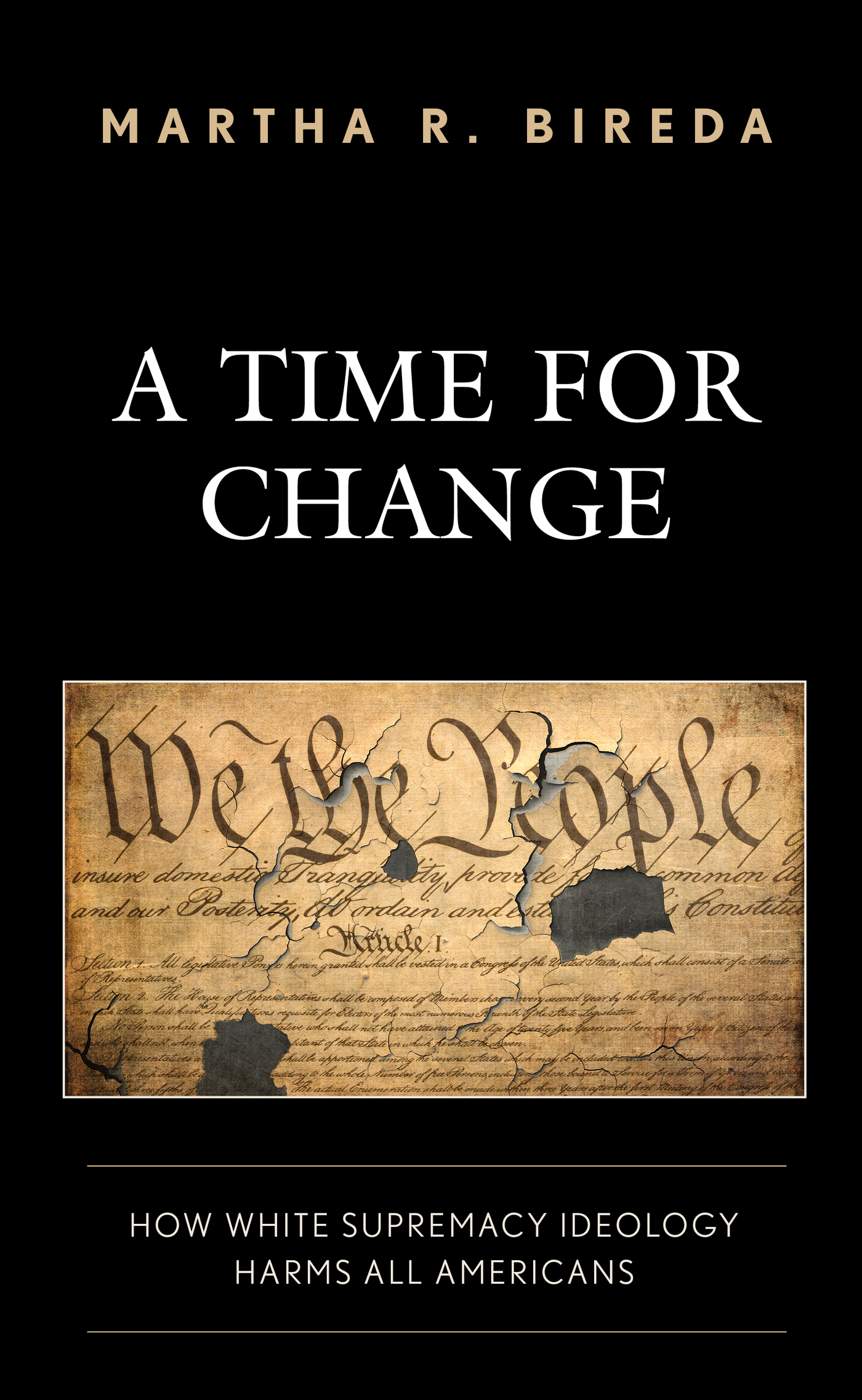

A Time for Change

A Time for Change

How White Supremacy Ideology Harms All Americans

Martha R. Bireda

ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

6 Tinworth Street, London SE11 5AL, United Kingdom

Copyright 2021 by Martha R. Bireda

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bireda, Martha R., author.

Title: A time for change : how white supremacy ideology harms all Americans / Martha R. Bireda.

Description: Lanham : Rowman & Littlefield, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references. | Summary: The starting point for eliminating the virus of white supremacy ideology from our culture must be in our educational system. This book is intended as a vaccine to help eliminate the damage and to prevent future generations from being infected.Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021000812 (print) | LCCN 2021000813 (ebook) | ISBN 9781475857412 (cloth) | ISBN 9781475857429 (paperback) | ISBN 9781475857436 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Multicultural educationUnited States. | Anti-racismStudy and teachingUnited States. | WhitesRace identityStudy and teachingUnited States. | White supremacy movementsUnited States. | Social justice and educationUnited States.

Classification: LCC LC1099 .B52 2021 (print) | LCC LC1099 (ebook) | DDC 370.1170973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021000812

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021000813

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

To the first African and European bondservants who lived in harmony fifty years before racism was thrust upon them for the gain of others.

Foreword

From 1865 to 1898, a little-known miracle took place in my hometown of Wilmington, North Carolina, a pleasant-looking, flower-filled, pine-tree-laden port city. Its the seat of New Hanover County, a peninsula bordered by the Cape Fear River, the Intracoastal Waterway and the Atlantic Ocean. Founded in 1739, Wilmington, located in what is called the Lower Cape Fear region, has always been a very isolated place, out of reach for most of the state. The county is situated on the southeast end of the state and resembles the tip of a womans high-heeled shoe. So, it was no wonder that the rest of the world didnt know about this fascinating nineteenth-century inspiring miracle.

After the Civil War, Wilmington had become what some newly freed African slaves called a mecca. They had heard and some had read that there were good jobs and opportunities in Wilmington. They started moving there so much so that within a few years, blacks made up the majority of what turned out to be a very prosperous city. They were able in a short time to turn Wilmington into a model for other freedmen to show them how they could attain political, economic, and social status so soon after the war.

By the 1890s, Republicans (black and white) were able to join hands with the newly conceived Populist Party and win elections. In fact, the states governor and United States senator were both Fusionists. John Hope Franklin has written: In 1894 such a combination seized control of the North Carolina legislature. Immediately, the Democratic machinery was dismantled and voting was made easier, so that more Negroes could vote. Negro office holding soon became common in the eastern Black Belt of the state. The fusion legislature of 1895 named 300 Negro magistrates. Many counties had Negro deputy sheriffs, Wilmington had fourteen Negro police, and New Bern had both Negro policemen and aldermen. One prominent Negro, James H. Young, was made chief fertilizer inspector and director of the state asylum for the blind; and another, John C. Dancy, was appointed collector of the Port of Wilmington (Franklin, 1967).

By October 1897, the city of Wilmington (population, 1890 census: 10,089 whites and 13,937 blacks) was completely governed by Fusionists. Mayor Salis P. Wright, a Republican, and his board of four black aldermen (Andrew J. Walker, Owen Fennell, Elijah M. Green, and John G. Norwood) and six white aldermen (W. E. Springer, W. E. Yopp, B. F. Keith, A. J. Hewlett, D. J. Benson, and H. C. Twining) held office. Other black officeholders included: Charles Norwood, the New Hanover County treasurer; Henry Hall, assistant sheriff; Dan Howard, city jailer; John Taylor, customs bookkeeper, and David Jacobs, county coroner.

Wilmingtons white Democrats resented these nine black officeholders. They contended that the citys black population was becoming insolent and impudent. One Democrat wrote: Conditions in Wilmington were becoming unbearable. It had become most uncomfortable for white women and girls to appear on the streets, as some of them had been elbowed off the sidewalks by colored women. Many colored men were insolent, because political developments had given them an erroneous idea of their position in public affairs. Their white leaders had misguided them while making suit their own selfish ends (Howell, p. 178).

In January of 1898, the white Democrats prepared quietly but effectively to overthrow the fusion government. A group called the Secret Nine (Hugh MacRae, J. Allen Taylor, Hardy Fennel, W. A. Johnson, L. B. Sasser, William Gilchrist, P. B. Manning, E. S. Lathrop, and Walter L. Parsley) met at the home of Hugh MacRae to map strategy. The city was divided into sections and men were placed in charge of each area. The whites also armed themselves with repeating shotguns, rifles, and pistols. I doubted if there was a community in the United States that had as many weapons per capita as here in Wilmington, boasted one of the Nine. The group, however, decided to adopt a wait-and-watch policy. They feared harsh reprisal from the local Fusionist authorities whom they dubbed The Big Four (referring to Dr. Salis P. Wright, the mayor; G. Z. French, the former postmaster of Wilmington and acting sheriff of New Hanover County; W. H. Chadbourn, the postmaster; and F. W. Foster). The Nine detested the Four because they controlled the majority voters, the Negroes, who always voted the Republican ticket as that was the political faith of their emancipator, Abraham Lincoln. This control of the Negro vote assured these Republican office holders a continuity in the office and local influence (Hayden, p. 3).

The white Democrats were convinced that they had to recover their government for economic reasons too. They had become frustrated with the number of blacks with higher paying jobs. They agreed that this practice was retarding the citys growth. One local Democrat wrote: Negroes were given preference in the matter of employment for most of the towns artisans were Negroes, and numerous white families in the city faced bitter want because their providers could get little work as brick masons, carpenters, mechanics; and this economic condition was aggravated considerably by the influx of many Negroes, and Wilmington was really becoming a city of Lost Opportunities for the working class whites (Hayden, p. 2).

Next page

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.