2016 by University Press of Colorado

Published by University Press of Colorado

5589 Arapahoe Avenue, Suite 206C

Boulder, Colorado 80303

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of The Association of American University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State University, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Metropolitan State University of Denver, Regis University, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, Utah State University, and Western State Colorado University.

This paper meets the requirements of the ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

ISBN: 978-1-60732-395-2 (cloth)

ISBN: 978-1-60732-396-9 (ebook)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Pierce, Jason (Jason Eric)

Making the white man's West : whiteness and the creation of the American West / by Jason E. Pierce.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-60732-395-2 (cloth : alkaline paper) ISBN 978-1-60732-396-9 (ebook)

1. West (U.S.)Race relationsHistory. 2. WhitesWest (U.S.)History. 3. WhitesRace identityWest (U.S.)History. 4. British AmericansWest (U.S.)History. 5. RacismWest (U.S.)History. 6. Cultural pluralismWest (U.S.)History. 7. Frontier and pioneer lifeWest (U.S.) 8. West (U.S.)History19th century. 9. West (U.S.)History20th century. I. Title.

F596.2.P54 2016

305.800978dc23

2015005246

25 24 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

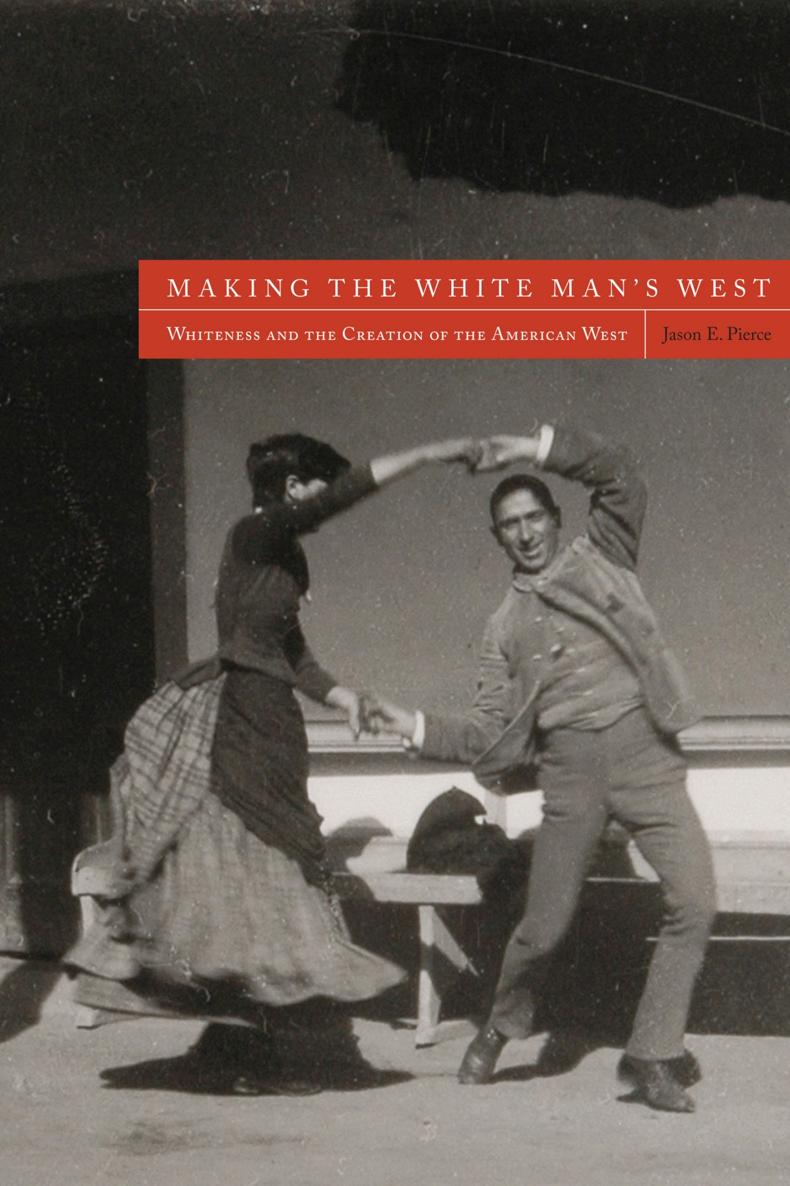

Cover photograph: Charles Fletcher Lummis dancing with a member of the Del Valle family. Courtesy, Braun Research Library Collection, Southwest Museum, Autry National Center, Los Angeles, CA.

For my loving and patient Mondie, my ebullient boys, and my teachers for whom this is a small payment on a large debt.

Preface

The trans-Mississippi West seemed destined to foster and shelter the white race. Concretions of myth and reality built up a society in which whites occupied the pinnacle, exercising power and control over non-white peoples. Myth and reality became inseparable, each supporting the other. The resulting society appeared as a refuge where Anglo-Americans could exist apart from a changing nation, a nation increasingly inhabited by non-Anglo and potentially incompatible immigrants. The overwhelmingly white population in certain areas of the West (the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains) reified the ideology of a white-dominated West, while the mythology obscured the presence of Indians, Hispanics, and Asians in California and the Southwest. The resulting society appeared, therefore, as a homogeneous population of Anglo-American whites, and this became the white mans West. The purpose of this work, then, is to look at how the idea of the West as a white racial refuge and the settlement of the region by Anglo-Americans interacted to create a region dominated by white Americans. Together, the continuing settlement of supposedly desirable Anglo-Americans and intellectual justifications underlying and supporting this settlement formed something of a feedback loop. The myth supported the reality, and reality supported the myth.

Beginning in the 1840s, white Americans increasingly saw opportunity in the West, finding a sense of mission in expansion to the ocean, a belief encapsulated in the term Manifest Destiny (and the bane of students in introductory courses in US history). Accomplishing this conquest fell to the rugged, individualistic white settler, the homespun hero of a new American nation. In The Winning of the West, Theodore Roosevelt, for example, celebrated white frontiersmen, the restless and reckless hunters, the hard, dogged frontier farmers [who] by dint of grim tenacity overcame and displaced Indians, French, and Spaniards alike, exactly as, fourteen hundred years before Saxon and Angle had overcome and displaced Cymric and Gaelic Celts. Driven by instinct and desire, these intrepid settlers fought to claim a new continent. They warred and settled, he continued, from the high hill-valleys of the French Broad and the Upper Cumberland to the half-tropical basin of the Rio Grande, and to where the Golden Gate lets through the long-heaving waters of the Pacific. Roosevelt argued that these men, while inheritors of a Germanic-English ancestry, stood as representatives of a new people. It is well, he warned, always to remember that at the day when we began our career as a nation we already differed from our kinsmen of Britain in blood as well as name; the word American already had more than a merely geographic signification. A continent tamed, the native population defeated, and American institutions rooted in new soilall marked the legacy of the white mans West. Roosevelt saw in this process a clear demonstration of the continuing march of Anglo civilization. Just as the Saxons and Angles had conquered the ancient Celts, their descendants wrested control of North America from inferior Indians, Spaniards, and Frenchmen.

These lesser groups, in particular American Indians, played merely the foil to the heroic frontiersman. Indeed, Roosevelts use of racialized terms like blood signified his view that race played the key role in determining the success of these new Americans, a group he saw as having a very narrow racial and ethnic composition. Roosevelts ideas on race and American superiority were remarkable only in their conformity to the common view of the day: the West had been settled by tough, individualistic, freedom-loving Anglo-Americans. This mythology, and the society it helped create and justify, soon came to seem natural and self-evident. Had not these brave whites tamed and settled the Wild West after all?

While historians and novelists could celebrate a white mans West, the reality proved more problematic. Non-whites had played important roles in the settlement of the region, roles that largely went unnoticed for decades. The West in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries included the largest populations of Hispanics, American Indians, and Asians in the nationhardly the racial monolith celebrated in the imagination. Yet there nevertheless existed kernels of truth in the idea of a white mans West. The presence of those racial and ethnic groups had indeed been obscured and their positions in society marginalized. In various ways, religion, political values, economic motives, and violence helped carve out areas of the West where whites composed the vast majority of the population (as in the Dakotas) or presided over non-white groups through political control and intimidation, as in California. Through these mechanisms, whites came to control the West, fashioning it into something that approximated the white mans West of the imagination.

In the twentieth-first-century West, the legacy of a society dominated by whites remains powerful, an insistent echo that somehow refuses to die. At issue is the question of who controls the region. As the historian Patricia Nelson Limerick asked, Who [is] a legitimate Westerner, and who [has] a right to share in the benefits of the region? When white Americans conquered the West, they instituted a process of control based around racial identity that forced the regions many minority groups to cling to the peripheries of power, society, and even space, as in the case of Indian reservations. Despite its long history of racial diversity, many promoters, developers, and dreamers touted the West as the ideal location for a society of Anglo-Saxon whites. Blessedly free of undesirable immigrantsthose Eastern and Southern European hordes, descending upon the Eastern Seaboard in the thousandsthe Anglo-American could find refuge and respect in the West. This dream of a white refuge never fully died.

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of The Association of American University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of The Association of American University Presses.