MORE ADVANCE PRAISE FOR BIND US APART

Nicholas Guyatt brilliantly captures the tragically unintended consequences of liberal reformers efforts to create a just and enlightened multiracial society in the new United States. Dedication to the principles of the Declaration of Independence ultimately led reformers to embrace both the colonization of former slaves and the removal of Native Americans. Sympathetically engaging with his well-intentioned subjects, Guyatt compels us to engage with what it has meantand still meansto be American. Powerfully argued and beautifully written, Bind Us Apart is essential reading.

Peter S. Onuf, author of Jeffersons Empire: The Language of American Nationhood

Connecting Indian removal and the African colonization movement to early US liberalism, Nicholas Guyatt offers a new origins story for American segregation. Brilliant and engrossing, Bind Us Apart reinterprets a formative era, while identifying legacies that continue to shape the present.

Christina Snyder, author of Slavery in Indian Country: The Changing Face of Captivity in Early America

In colorful and lively prose, Nicholas Guyatt recovers the history of white Americans who agonized over slavery and the treatment of Native Americans. Some were famous presidents and generals; others were obscure figures. Almost all rejected the nations founding credo of all men are created equal to promote racial separation instead. A fascinating and little known history.

Margaret Jacobs, author of White Mother to a Dark Race

Copyright 2016 by Nicholas Guyatt

Published by Basic Books,

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address Basic Books, 250 West 57th Street, 15th floor, New York, NY 10107.

Books published by Basic Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

Designed by Jack Lenzo

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Guyatt, Nicholas, 1973

Title: Bind us apart: how enlightened Americans invented racial segregation / Nicholas Guyatt.

Description: New York, NY: Basic Books, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015041451 (print) | LCCN 2015045766 (ebook) | ISBN 9780465065615 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: RacismUnited StatesHistory. | United StatesRace relationsHistory18th century. | United StatesRace relationsHistory19th century. | Indians of North AmericaColonizationUnited States. | African AmericansColonizationAfrica. | BISAC: HISTORY / United States / 19th Century.

Classification: LCC E184.A1 G985 2016 (print) | LCC E184.A1 (ebook) | DDC 305.800973dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015041451

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Tess, Sid, and Kate

When you are persecuted in one city, flee unto another.

Edward Coles, Notes on Slavery (after Matthew 10:23)

We often congratulate ourselves more on getting rid of a problem than on solving it.

W. E. B. Du Bois, The Suppression of the African Slave Trade

Table of Contents

Guide

Contents

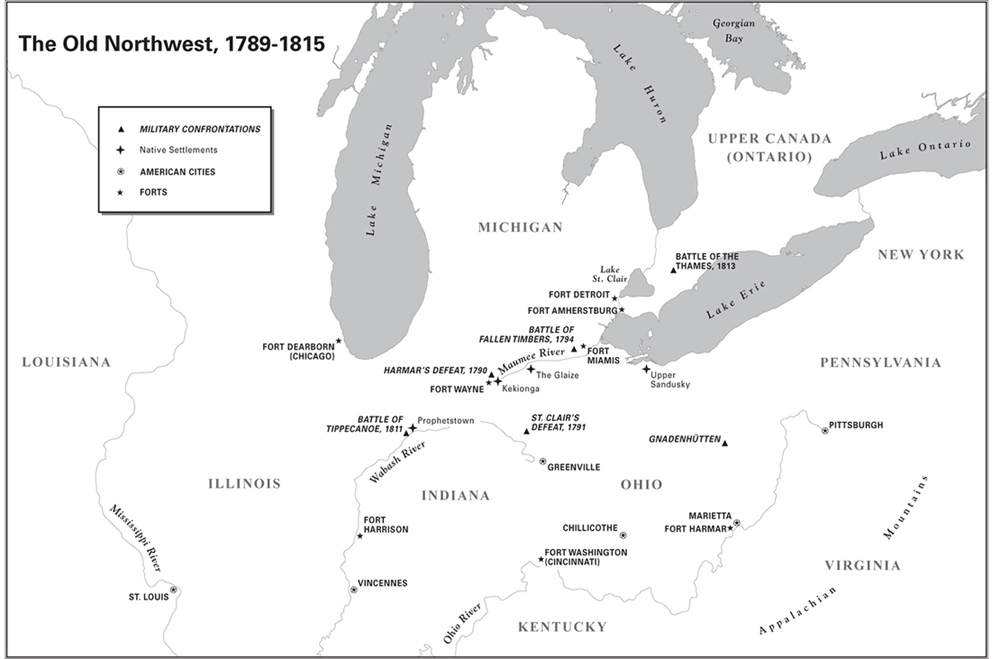

E DWARD COLES HAD A LOT on his mind. In July 1814 he was private secretary to James Madison and spent his days managing the presidents business at a time of war. The United States had been fighting Britain and its Native American allies for nearly three years. Coles and Madison would be forced to flee the White House just a few weeks later, when British troops invaded and razed Washington. Coles still made time during that anxious month to write to Thomas Jefferson about the nations founding dilemma. I never took up my pen with more hesitation, or felt more embarrassment than I now do in addressing you on the subject of this letter, wrote Coles. But given the leisure now afforded by his well-deserved retirement, might Jefferson be able to devise some plan for the gradual emancipation of slavery?

Coles was twenty-seven years old. He came from a wealthy Virginia family, and had inherited twenty slaves from his father in 1808. The year before, as a student at the College of William and Mary, he had decided that he would not and could not hold my fellow man as a slave. The insight came to him in class one day, when he was listening to the president of the college lecturing and explaining the rights of man. Coles asked his professor (in the simplicity of youth) how it was possible to reconcile human rights and the equality of mankind with slaveholding. I can never forget his peculiarly embarrassed manner, Coles later recalled. He frankly admitted it could not rightfully be done, and that slavery was a state of things that could not be justified on principle. The only excuse for failing to end slavery was the difficulty of getting rid of it, his professor suggested. Coles continued to harass him when the class was over, insisting that the practical problems of emancipation were no excuse for apathy or inaction. In 1814, he was making the same point to Thomas Jefferson.

Jefferson had been retired for five years at Monticello. He spent his days reading, entertaining, and corresponding with an extraordinary range of people. Sally Hemings, with whom he had been in a sexual relationship for more than a quarter of a century, was living in the servants quarters in the south wing. Four of Hemingss six children had survived past infancy and were still on the mountain. (All enslaved, like their mother.) Jefferson was sixty-seven years old. He had criticized the institution of slavery since his time in the Virginia governors mansion in the 1770s, and as president of the United States hed signed the bill that ended American participation in the international slave trade. And yet the nations slave population was still creeping upward. Edward Coles badgered anyone who would listen on this topic. When he and James Madison strolled through the nations capital and encountered gangs of negroes, some in irons, Coles upbraided the president for doing nothing to secure the rights of man. But Coles felt that Jefferson had a special responsibility to lead the nations struggle against slavery. He was, after all, the immortal author of all men are created equal, the nations founding creed. The time had arrived to put into complete practice those hallowed principles contained in that renowned Declaration.

In his reply, Jefferson conceded that the love of justice and the love of country plead equally the cause of these people. But what would happen to them (and their white neighbors) if slaves were suddenly set free? For decades, Jeffersons anxieties about integration had weakened his antislavery convictions. Coles had his own solution: he would take his freed slaves to the western states and forge a new life with them there. Jefferson was alarmed by this plan to abandon them in the midst of white people. He urged a different solution: slaves should be freed gradually and on condition that they leave the United States. Coles should temper his radicalism until he found a way to reconcile all men are created equal with the need for racial separation. The former president would offer his best hopes to this effort, but no more. I have overlived the generation with which mutual labors and perils begat mutual confidence and influence. Antislavery, Jefferson declared, was an enterprise for the young.

Next page