SELF-EVIDENT TRUTHS

Self-Evident Truths

Contesting Equal Rights from the Revolution to the Civil War

RICHARD D. BROWN

Yale UNIVERSITY PRESS

NEW HAVEN AND LONDON

Copyright 2017 by Richard D. Brown.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Electra type by Newgen North America.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016943623

ISBN 978-0-300-19711-2 (hardcover)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

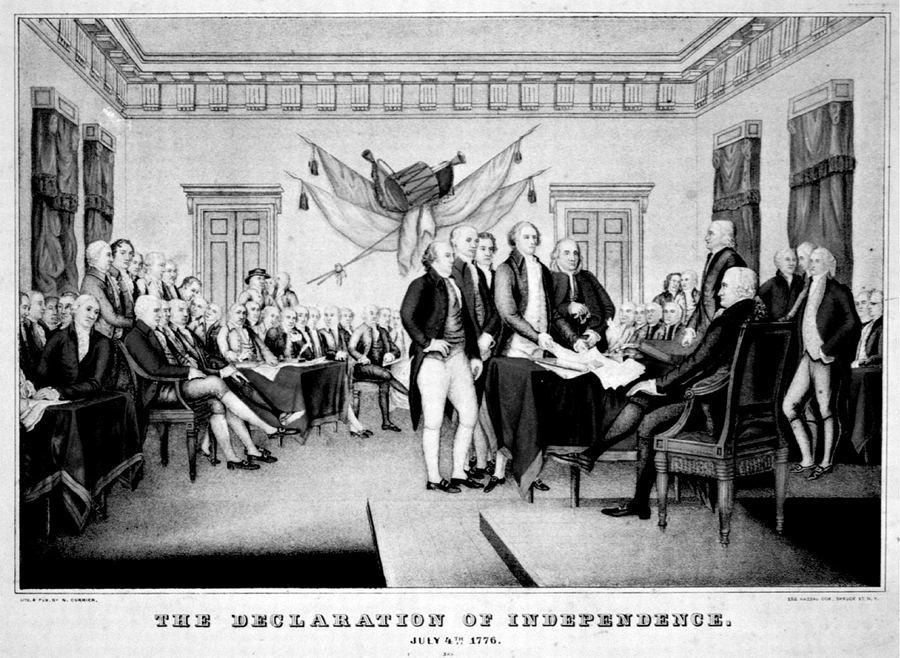

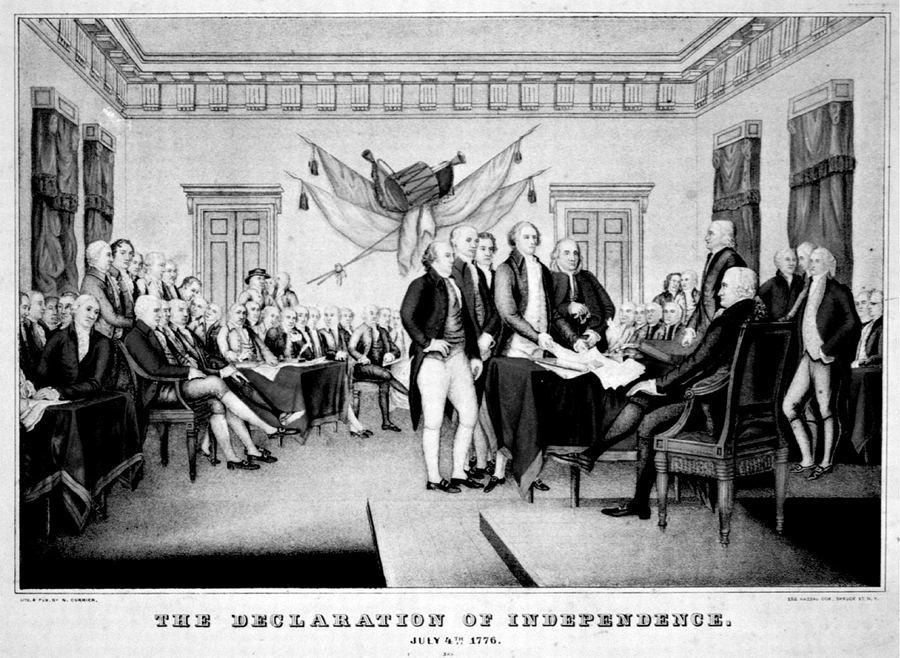

John Trumbull, The Declaration of Independence, N. Currier, 183556. Curriers print represents the heightened popular admiration for the Revolution and especially the Declaration during the generation preceding the Civil War. Courtesy, Library of Congress.

PREFACE

The bold, inspiring promise of the Declaration of Independence has long possessed a powerful grip on Americans political imagination. The idea that the United States must be a land of equality, where every person should realize equal opportunities for life, liberty, and the pursuit of happinesswith privilege banishedis fundamental to the nations modern creed. Yet it would be naive to suppose that this ideal has ever accurately reflected American reality. Privilege, sometimes written into law and sometimes merely customary, is a historical fact of life. Statutes have privileged men, property holders, whites, adults, citizens, Protestants, and heterosexuals. Custom has extended these and subtler forms of privilege, like class, ethnicity, and education, into American society broadly. As a result, some have come to regard the Declarations promise as hollow rhetoricmerely Patriots propaganda. Why should anyone take these wordsall men are created equalseriously when they came from the pen of a slave master and were adopted by a Congress of privileged gentlemen, many of whom were also slaveholders?

The point is debatable. We should not allow the patriotic mythologies that wash over us from childhood to cloud our vision. But neither should we interpret the Declaration to make a weapon in the political battles of our own time. Considering the Declarations self-evident truths maturely requires us to examine their origins and trajectories across the centuries. It is possible that the language of the Declaration was propaganda. Certainly it was an explicitly political text intended to arouse popular support. But, for it to succeed, the ideas it invoked must have been meaningfuleven inspiringfor many Americans. Viewing the Congress of gentlemen with full-blown skepticism could be a mistake. Maybe their political machinations were propelled not only by ambition and selfish interests but by ideas and ideals as well.

However critics have judged the founding fathers, they have never accused them of ignorance or stupidity. Obviously Patriot leaders recognized slavery and class privileges in their own time: yet they embraced egalitarian rhetoric. In the short term that rhetoric may have been the key to mobilizing common men to fight; but could John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, and their colleagues have been so short-sighted and so confident of their power as to suppose that their language of equality would have no consequences? Among the founding fathers and their constituents, some, we do not know how many, took the language of the Declaration to heart. Dwelling as they did in a society of rank and privilege, some continental congressmen and their descendants expressed egalitarian hopes.

This study aims to investigate the proposition that the self-evident truths proclaimed in the Declaration were not simply rhetorical window-dressing but inspired serious aspirations from the moment they were proclaimed. The constitutions, laws, and politics of the decades between independence and the Civil War reveal the ways that Americans embedded the Revolutions egalitarian impulse in their discourse. Equal rights are the central concern of this study because the Revolution promised equal rights, not any broader form of equality. So our investigation begins with constitutions and bills of rights.

But it also moves into courtrooms, because courts were often a place where rights were defined with precision, where criminal trials and divorce cases tested whether reality matched the rhetoric of equal rights. Because capital trials especially displayed the most intense and uninhibited arguments, they permit us to glimpse collisions between equal rights principles and customary prejudices and privileges. Here, too, the impact of popular opinion on legal procedures challenged the principle of equal justice under law.

The chapters that follow examine contests over equal rights in six central arenas of public concernreligion, nationality and ethnicity, race, gender, age, and social class. Each chapter explores the ways in which Americans came to realize, in whole or in part, the ideal of equal rights expressed in the Declarationor to disavow that ideal. Though evidence is drawn from all parts of the early Republic, it is weighted toward the Northeast and New England. That is partly owing to the availability of sources and to my familiarity with that regions history. Given the broad scope of this study, even with extensive research in every state, the insights and answers provided in these pages could never be definitive and must rely on some mixture of empirical and impressionistic evidence.

This inquiry cannot treat the entire United States thoroughly in the era from independence to the Civil War, but I hope that it provides a useful beginning. No region was more committed to the realization of equal rights than New England and the Northeast, so if anything, the information drawn from this region may overstate the impact of Revolutionary equal rights doctrine. Bearing that in mind, readers will make their own judgments in light of evidence that cannot be comprehensive. Because I treat a broad range of experiences in North and South and the Old West, especially as revealed in court cases, I aim to provide insights into the practical, everyday complexities of contests over equal rights. Taken together they illuminate the ways in which Americans struggled with one another over recognizing the principle that all men are created equal.

This book contends that the Declarations fateful phrase was not merely high-flown rhetoric. For many Revolutionaries it expressed their profound commitment to a new political and social contract. In the words proclaimed by the Continental Congress in 1782, the independent United States was to be a novus ordo seclorum, a new order of the ages. But in a country where inequality was customary and often written into law, where people of different religions, ethnicities, nationalities, and races competed with one another, the distance between their declaration and its fulfillment was bound to be arduous and conflict-ridden. Moreover, Americans all-but-unanimous commitment to private propertyand to its heritability across the generationsprovided a structural impediment to the full realization of equal rights that few were ready to confront, prompting William Dean Howells to remark, in

Next page