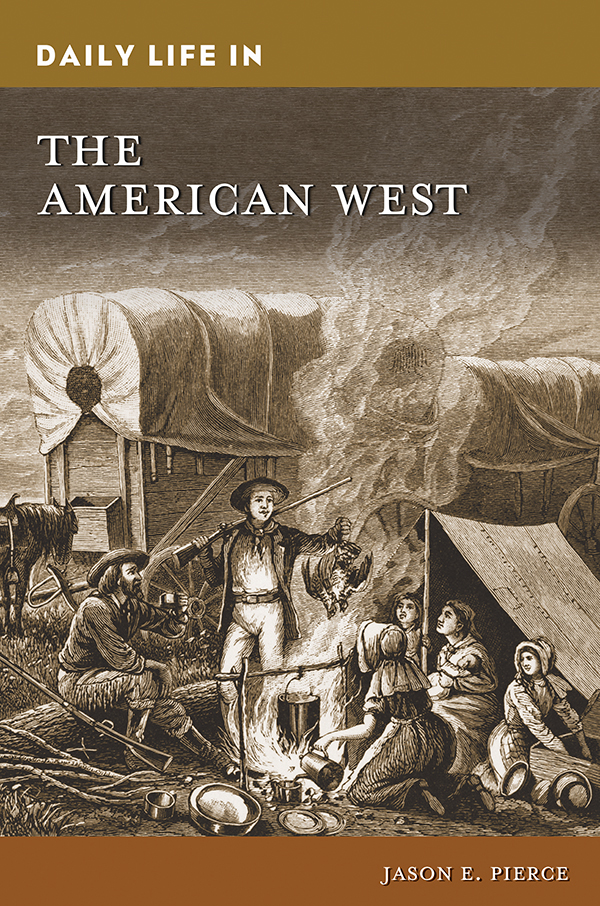

DAILY LIFE IN

THE AMERICAN

WEST

Recent Titles in The Greenwood Press Daily Life Through History Series

18th-Century England, Second Edition

Kirstin Olsen

Colonial New England, Second Edition

Claudia Durst Johnson

Life in 1950s America

Nancy Hendricks

Jazz Age America

Steven L. Piott

Women in the Progressive Era

Kirstin Olsen

The Industrial United States, 18701900, Second Edition

Julie Husband and Jim OLoughlin

The 1960s Counterculture

Jim Willis

Renaissance Italy, Second Edition

Elizabeth S. Cohen and Thomas V. Cohen

Nazi-Occupied Europe

Harold J. Goldberg

African American Slaves in the Antebellum

Paul E. Teed and Melissa Ladd Teed

Women in Postwar America

Nancy Hendricks

Women in Ancient Egypt

Lisa K. Sabbahy

Women in Ancient Rome

Sara Phang

Women in Chaucers England

Jennifer C. Edwards

Life in Anglo-Saxon England

Sally Crawford

DAILY LIFE IN

THE AMERICAN

WEST

JASON E. PIERCE

The Greenwood Press Daily Life Through History Series

Copyright 2022 by ABC-CLIO, LLC

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Pierce, Jason (Jason Eric), author.

Title: Daily life in the American West / Jason E. Pierce.

Description: [Santa Barbara, California] : Greenwood, [2022] | Series: The Greenwood Press daily life through history series | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022001350 (print) | LCCN 2022001351 (ebook) | ISBN 9781440876196 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781440876202 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Frontier and pioneer lifeWest (U.S.) | West (U.S.)Social life and customs19th century. | West (U.S.)History19th century.

Classification: LCC F596 .P53 2022 (print) | LCC F596 (ebook) | DDC 978dc23/eng/20220114

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022001350

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022001351

ISBN: 978-1-4408-7619-6 (print)

978-1-4408-7620-2 (ebook)

26 25 24 23 22 1 2 3 4 5

This book is also available as an eBook.

Greenwood

An Imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC

ABC-CLIO, LLC

147 Castilian Drive

Santa Barbara, California 93117

www.abc-clio.com

This book is printed on acid-free paper

Manufactured in the United States of America

CONTENTS

Eastward I go only by force, Henry David Thoreau famously said, but westward I go free. It is a famous line that has aged into clich, the kind of thing that ends up emblazoned on posters of gorgeous Western landscapes: snowcapped peaks; stark, ruddy deserts; or the molten globe of a setting sun sinking into the Pacific. Indeed, that is exactly what it has become, and you can download wallpapers for your personal computer from a website called Quote Fancy with the line emblazoned on it.

Less well known is the essay in which that line appears. The essay in question, Walking, appeared in The Atlantic in June 1862, a month after Thoreaus death. In it, Thoreau celebrated the benefits of sauntering, casually strolling for hours wherever one felt compelled to go, but Walking was no mere advice column on the mental and physical benefits of a good walk. It was also a rumination on the importance of open spaces. Thoreau groused, Nowadays almost all mans improvements, so called, as the building of houses and the cutting down of the forest and of all large trees, simply deform the landscape, and make it more and more tame and cheap (Thoreau 1862). The only region as yet untainted by excessive civilization, Thoreau believed, was the West. Even from Massachusetts, the American philosopher could feel the pull of the West when he left his house on his daily walks, and he believed it spoke to something universal in the American spirit. I should not lay so much stress on this fact [of going west], if I did not believe that something like this is the prevailing tendency of my countrymen, he observed. I must walk toward Oregon, and not toward Europe. And that way the nation is moving, and I may say that mankind progress from east to west (Thoreau 1862). For Thoreau, and he believed his countrymen as well, going west meant becoming more uniquely American.

Thoreau would not live to see the West fully settled, and perhaps, for him, it was just as well. A mere seven years after his death, the completion of the first transcontinental railroad tethered the nation together, making the once arduous and dangerous crossing of the continent a comparatively easy affair. A bit more than 15 years after that, in 1886, Geronimo and a few dozen other Chiricahua Apache surrendered at Skeleton Canyon, in the Arizona Territory, marking an end to the centuries of conflict between whites and Indian peoples, a finale with the tragic exception of one bitter coda that would occur on a December morning in 1890.

Indeed, by the 1880s, the wildest days of the Wild West had already lapsed into memory and, increasingly, mythology. Towns and cities sprang up; railroads crisscrossed the region; mines poured fourth tons of gold, silver, copper, and coal; and the Wests wild places, its crenelated canyons, towering mountains, and sinuous rivers that so captivated Thoreaus imagination had been overrun by miners, lumberjacks, and engineers bent on transforming the region to make it serve the interests of an increasingly powerful industrial nation. The West would never again be as seemingly pristine, but people like Thoreauand a bit later Theodore Roosevelt, John Muir, and otherswould have an effect on Americans as well, convincing them that there was something to be said for leaving some places alone, leaving wildlands as part of the nations inheritance. Conservation, the belief that resources should be used and managed wisely, and preservation, the desire to leave some places without obvious signs of human interference, both found support at the turn of the last century, and the West offered most of the best remaining land for such reforms. Theodore Roosevelt, the first president to have spent much time in the West, championed these efforts, setting aside more land as national parks, national monuments, and national forests than all presidents before or since, and the vast majority lay in the West.

The West lived on, as well, in the imaginations of all Americans and even among peoples in other nations. By the late 19th century, Americans, especially young Americans, consumed the various dime novels that recounted the (generally exaggerated) exploits of Western heroes and outlaws like Buffalo Bill, Billy the Kid, and Calamity Jane. The transition of these mass-market heroes to film and radio proved remarkably easy, and by the mid-20th century, celluloid cowboys rode to glory every night of the week on big screens and flickering home television sets. Americans, even in an age of industrial conveniences like air-conditioning, TV dinners, and automobiles, could imagine themselves confronting danger on the edges of an always vanishing Western frontier. Many believed, as Frederick Jackson Turner had asserted in 1893, that the frontier was the place where Americans became truly American.