Mirzoeff - How to See the World: A Pelican Introduction

Here you can read online Mirzoeff - How to See the World: A Pelican Introduction full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2015, publisher: Penguin Books Ltd, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

How to See the World: A Pelican Introduction: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "How to See the World: A Pelican Introduction" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Mirzoeff: author's other books

Who wrote How to See the World: A Pelican Introduction? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

How to See the World: A Pelican Introduction — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "How to See the World: A Pelican Introduction" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

INTRODUCTION

How to See the World

CHAPTER 1

How to See Yourself

CHAPTER 2

How We Think About Seeing

CHAPTER 3

The World of War

CHAPTER 4

The World on Screen

CHAPTER 5

World Cities, City Worlds

CHAPTER 6

The Changing World

CHAPTER 7

Changing the World

AFTERWORD

Visual Activism

- , 2014

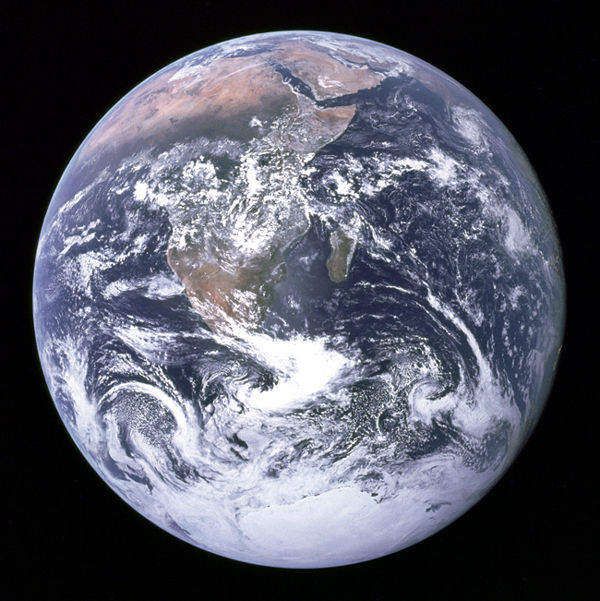

Figure 1 NASA , Blue Marble

In 1972, the astronaut Jack Schmitt took a picture of Earth from the Apollo 17 spacecraft, which is now believed to be the most reproduced photograph ever. Because it showed the spherical globe dominated by blue oceans with intervening green landmasses and swirling clouds, the image came to be known as Blue Marble.

The photograph powerfully depicted the planet as a whole, and from space: no human activity or presence was visible. It appeared on almost every newspaper front page around the world.

In the photograph, Earth is viewed very close to the edge of the frame. It dominates the picture and overwhelms our senses. Since the spacecraft had the sun behind it, the photograph was unique in showing the planet fully illuminated. The Earth seems at once immense and knowable. Taught to recognize the outline of the continents, viewers could now see how these apparently abstract shapes were a lived and living whole. The photograph mixed the known and the new in a visual format that made it comprehensible and beautiful.

At the time it was published, many people believed that seeing Blue Marble changed their lives. The poet Archibald MacLeish recalled that for the first time people saw the Earth as a whole, whole and round and beautiful and small. Some found spiritual and environmental lessons in viewing the planet as if from the place of a god. Writer Robert Poole called Blue Marble a photographic manifesto for global justice (Wuebbles 2012). It inspired utopian thoughts of a world government, perhaps even a single global language, epitomized by its use on the front cover of The Whole Earth Catalog, the classic book of the counterculture. Above all, it seemed to show that the world was a single, unified place. As Apollo astronaut Russell (Rusty) Schweickart put it, the image conveys

the thing is a whole, the Earth is a whole, and its so beautiful. You wish you could take a person in each hand, one from each side in the various conflicts, and say, Look. Look at it from this perspective. Look at that. Whats important?

No human has seen that perspective in person since the photograph was taken, yet most of us feel we know how the Earth looks because of Blue Marble.

That unified world, visible from one spot, often seems out of reach now. In the forty years since Blue Marble, the world has changed dramatically in four key registers. Today, the world is young, urban, wired and hot. Each of these indicators has passed a crucial threshold since 2008. In that year, more people lived in cities than the countryside for the first time in history. Consider the emerging world power Brazil. In 1960, only a third of its people lived in cities. By 1972, when Blue Marble was taken, the urban population had already passed 50 percent. Today, 85 percent of Brazilians live in cities, no less than 166 million people.

Most of them are young, which is the next indicator. By 2011, more than half the worlds population was under thirty; 62 percent of Brazilians are twenty-nine or younger. More than half of the 1.2 billion Indians are under twenty-five, and a similar young majority exists in China. Two-thirds of South Africas population is under thirty-five. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, 52 percent of the 18 million people in Niger are under fifteen and in most of sub-Saharan Africa, over 40 percent of the population is under fifteen. The populations of North America, Western Europe and Japan may be ageing, but the global pattern is clear.

The third threshold is connectivity. In 2012, more than a third of the worlds population had access to the Internet, up 566 percent since 2000. Its not just Europe and America that are connected: 45 percent of those with Internet access are in Asia. Nonetheless, the major regions that lack connection are sub-Saharan Africa (other than South Africa) and the Indian sub-continent, creating a digital divide on a global level. By the end of 2014, an estimated 3 billion people were online. By the end of the decade, Google envisages 5 billion people on the Internet. This is not just another form of mass media. It is the first universal medium.

One of the most notable uses of the global network is to create, send and view images of all kinds, from photographs to video, comics, art and animation. The numbers are astonishing: one hundred hours of YouTube video are uploaded every minute. Six billion hours of video are watched every month on the site, one hour for every person on earth. The 1834 age group watches more YouTube than cable television. (And remember that YouTube was only created in 2005.) Every two minutes, Americans alone take more photographs than were made in the entire nineteenth century. As early as 1930, an estimated one billion photographs were being taken every year worldwide. Fifty years later, it was about 25 billion a year, still taken on film. By 2012, we were taking 380 billion photographs a year, nearly all digital. One trillion photographs were taken in 2014. There were some 3.5 trillion photographs in existence in 2011, so the global photography archive increased by some 25 percent or so in 2014. In that same year, 2011, there were one trillion visits to YouTube. Like it or not, the emerging global society is visual. All these photographs and videos are our way of trying to see the world. We feel compelled to make images of it and share them with others as a key part of our effort to understand the changing world around us and our place within it.

The planet itself is changing before our eyes. In 2013, carbon dioxide passed the signature threshold of 400 parts-per-million in the atmosphere for the first time since the Pliocene era about three to five million years ago. Although we cannot see the gas, it has set in motion catastrophic change. With more carbon dioxide, warm air holds more water vapour. As the ice-caps melt, there is more water in the ocean. As the oceans warm, there is more energy for a storm system to draw on, producing storm after unprecedented storm. If a hurricane or earthquake creates what scientists call a high sea-level event, like a storm surge or tsunami, the effects are dramatically multiplied. Record-setting floods have followed around the world from Bangkok to London and New York, even as other areas from Australia to Brazil, California and equatorial Africa suffer unprecedented drought. The world today is physically different from the one we see in Blue Marble, and it is changing fast.

For all the new visual material, it is often hard to be sure what we are seeing when we look at todays world. None of these changes are settled or stable. It seems as if we live in a time of permanent revolution. If we put together these factors of growing, networked cities with a majority youthful population, and a changing climate, what we get is a formula for change. Sure enough, people worldwide are actively trying to change the systems that represent us in all senses, from artistic to visual and political. This book seeks to understand the changing world to help them and all those trying to make sense of what they see.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «How to See the World: A Pelican Introduction»

Look at similar books to How to See the World: A Pelican Introduction. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book How to See the World: A Pelican Introduction and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.