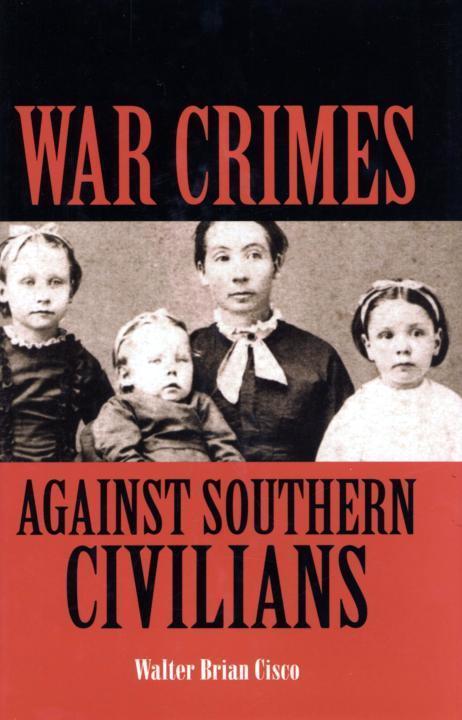

WAR CRIMES

AGAINST SOUTHERN

CIVILIANS

WAR CRIMES

AGAINST SOUTHERN

CIVILIANS

Walter Brian Cisco

For Hunter

Contents

.......................................... 15

An Introduction to Lincoln's War

"We Believe in a War of Extermination"

Keeping Missouri in the Union

"Burnt District"

Order No. 11

"Treason Must Be Made Odious"

Oppression in Tennessee

"Soldiers Are Not Expected to Be Angels"

Fredericksburg Pillaged

"1 Shut My Eyes for Two Hours "

The Sack of Athens

"Fleurs du Sud"

New Orleans Under Butler

"Randolph Is Gone"

Law and Order and Sherman

"Their Houses Will Be Burned and the Men Shot"

Tyranny in Tucker County

"The Best Government the World Ever Saw"

Milroy Rules Winchester

"Swamp Angel"

The Shelling of Charleston

"I Intend to Take Everything"

Banks Raids Louisiana

"No Strict Dichotomy"

The Lieber Code

"We Spent the Rest of That Day in the Dungeon "

Women and Children in Prison

"Make It a Desolation "

The Shelling of Atlanta

"As Captors, We Have a Right to It"

The Forced Evacuation of Atlanta

"Plundering Dreadfully from All Accounts"

Hunter in the Shenandoah

"Nothing Left for Man or Beast"

Sheridan's Devastation

"General Sherman Is Kind of Careless with Fire"

The Burning of Atlanta

"They Took Everything That Was Not Red-Hot or Nailed

Down"

March to the Sea

"Sometimes the World Seemed on Fire"

Sherman in South Carolina

"And What Do You Think of the Yankees Now?"

The Burning of Columbia

"We Must Make the Thing Pay Somehow"

Sherman in North Carolina

"Marne General Sherman Said War Was Hell"

Abuse of African-Americans

............................................. 187

............................................. 215

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due the staffs of the following institutions: the University of South Carolina's Thomas Cooper Library (particularly the longsuffering folks in the Interlibrary Loan Department) and South Caroliniana Library; Library of Congress; William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan; Special Collections Library, Duke University; Robert W. Woodruff Library, Emory University; and the Huntington Library.

I appreciate, too, all those individuals who contributed material, ideas, and encouragement: Clyde Wilson, Don Livingston, Tom Elmore, Randy Simpson, Bill Moody, and David Cisco. I only wish that I could have used every piece of information given me.

This is a better book for the advice, assistance, and inspiration of others. Any shortcomings are entirely the author's.

WALTER BRIAN CISCO

WAR CRIMES

AGAINST SOUTHERN

CIVILIANS

Chapter 1

An Introduction to

Lincoln's War

In the midst of his 1863 invasion of the United States, Gen. Robert E. Lee issued a proclamation to his men. After suffering for two years innumerable depredations by their enemies, some Southerners, soldiers and civilians, thought at last the time had come for retaliation. Lee would have none of that. He reminded his troops that "the duties exacted of us by civilization and Christianity are not less obligatory in the country of the enemy than in our own."

The commanding general considers that no greater disgrace could befall the army, and through it our whole people, than the perpetration of the barbarous outrages upon the unarmed and defenseless and the wanton destruction of private property, that have marked the course of the enemy in our own country...

It must be remembered that we make war only upon armed men, and that we cannot take vengeance for the wrongs our people have suffered without lowering ourselves in the eyes of all whose abhorrence has been excited by the atrocities of our enemies, and offending against Him to whom vengeance belongeth, without whose favor and support our efforts must all prove in vain.'

Accustomed as we are in our own time to war's unmitigated horrors, the injunction of Lee seems anachronistic if not quixotic, yet is a measure and reminder of how much has been lost.

Through the centuries, by common consent within what used to be called Christendom, there arose a code of civilized warfare. Though other issues are covered by the term, and despite lapses, it came to be understood that war would be confined to combatants. Thus limited, said historian F. J. P. Veale, "it necessarily followed that an enemy civilian did not forfeit his rights as a human being merely because the armed forces of his country were unable to defend him."' According to Veale, the amelioration of war's barbarism did not come as a direct result of Christianity, or even from the rise of European chivalry, but "as the product of belated common sense." As early as the eighteenth century, Swiss jurist Emeric de Vattel, author of The Law of Nations, expressed what should be obvious to any student of history: breaking the code on one side encourages violations by the other, multiplying hatred and bitterness that can only increase the likelihood and intensity of future wars.' "There is today," concluded Vattel in 1758, "no Nation in any degree civilized which does not observe this rule of justice and humanity."4

Yet warring against noncombatants came to be the stated policy and deliberate practice of the United States in its subjugation of the Confederacy. Shelling and burning of cities, systematic destruction of entire districts, mass arrests, forced expulsions, wholesale plundering of personal property, even murder all became routine. The development of Federal policy during the war is difficult to neatly categorize. Abraham Lincoln, the commander in chief with a reputation as micromanager, well knew what was going on and approved. Commanders seemed always inclined to turn a blind eye to their soldiers' proclivity for theft and violence against the defenseless. And though the attitude of Federal authorities in waging war on Southern civilians became increasingly harsh over time, there was from the beginning a widespread conviction that the crushing of secession justified the severest of measures. Malice, not charity, is the theme most often encountered.

Lincoln's embracing of "hard war" may have had consequences more far-reaching even than defeat of the South. Union general Philip Sheridan, in Germany to observe that empire's conquest of France in 1870, told Otto von Bismarck that defeated civilians "must be left nothing but their eyes to weep with over the war." The chancellor was said to have been shocked by the unsolicited advice. But the kind of warfare practiced by the Federal military during 1861-65 turned America-and arguably the whole world-back to a darker age. "It scarcely needs pointing out," wrote Richard M. Weaver, "that from the military policies of [William T.] Sherman and Sheridan there lies but an easy step to the total war of the Nazis, the greatest affront to Western civilization since its founding."'