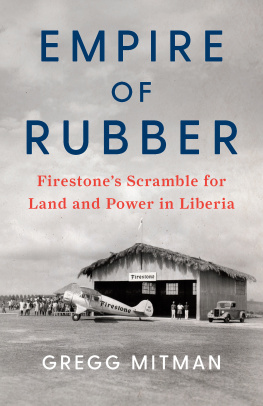

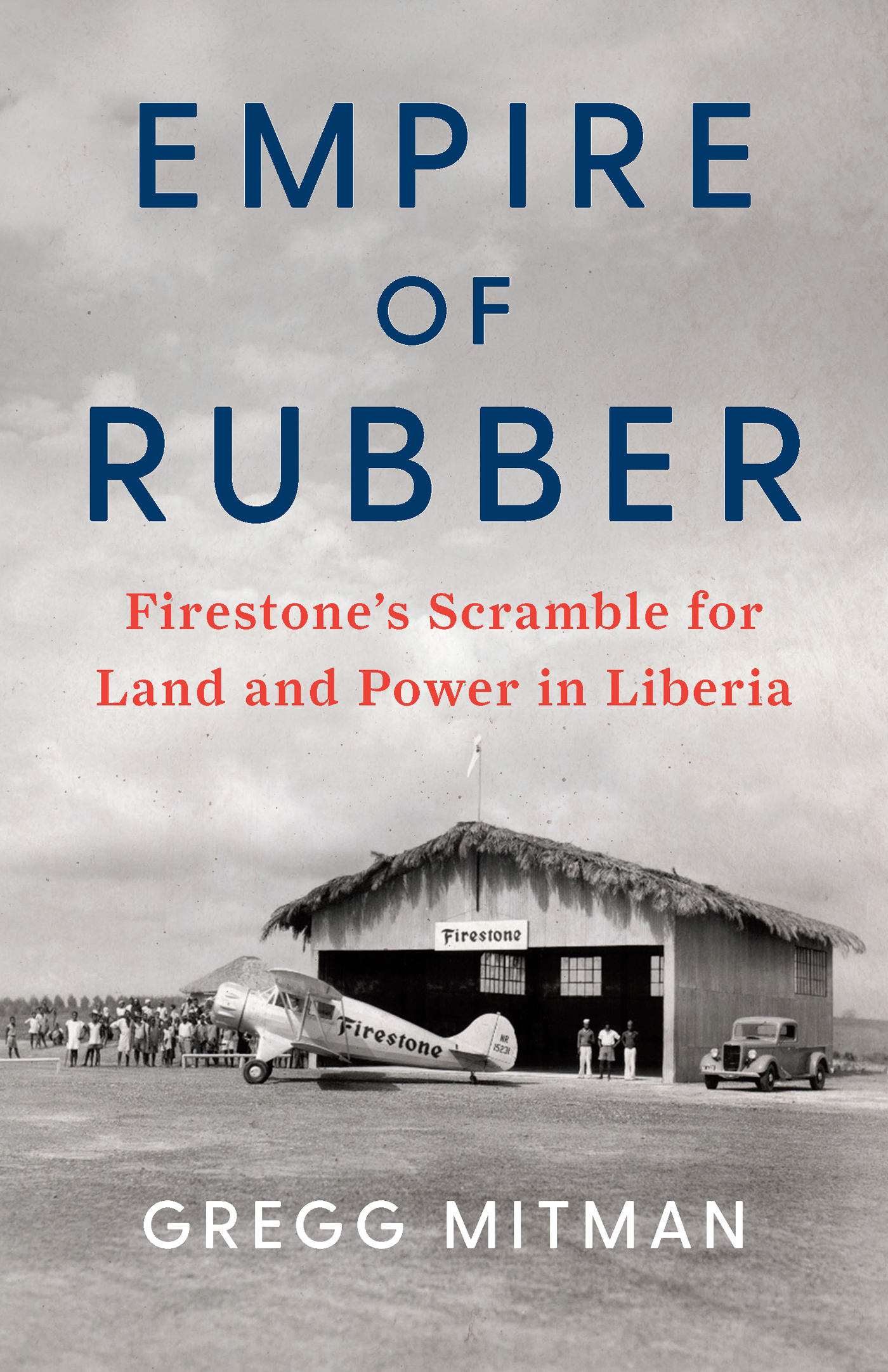

Empire of Rubber

Empire of Rubber

Firestones Scramble for Land and Power in Liberia

Gregg Mitman

For Emmanuel and Gomue

Contents

Preface

Evening rains have flushed the heat and dust from the air. An early morning breeze brings a cool freshness to the day. It is quiet at the rivers edge on the back patio of the Farmington Hotel, a $20 million, five-star luxury complex, opened in 2017 across from Liberias Roberts International Airport, also known as Robertsfield. The hotel mostly serves a foreign-business and donor-agency clientele able to spend $200 a night in a country where half the population lives on less than $2 a day. Our film crew will be working for the next few days at the nearby Liberian Institute for Bio-medical Research, which makes this hotel a convenient place to stay.

Also nearby the hotel is the town of Harbel, where the headquarters of the former Firestone Plantations Company, now Firestone Liberia, is located. Harbel is a shadow of what it was in an era when the natural wealth of the land was harvested to fill the coffers of American rubber barons, steel magnates, and Liberian elites.

The hotels patio looks out on the Farmington River, after which the hotel is named. A few miles downstream, the fresh waters of the Farmington mix with the Atlantic Oceans saline waters to form a unique estuarine habitat of mangrove forests and barrier islands that support a diversity of life. Across the river, children are at play in Zangar Town. I can see palm and banana trees on the towns edge and, interspersed among the mud brick homes, small garden plots, likely growing peppers, cassava, and other Liberian staples. Throughout Liberia, such crops provide sustenance, cash, and a claim to land rights in a country where land is life. Nearby, a dugout canoe, fashioned from a huge log, ferries people from one side of the river to the other.

In the 1940s this area was abuzz with United States Army personnel, Firestone engineers, and Liberian workers. They labored to quickly build an airport to be operated under military contract by Pan American Airways, initially called Roberts Field, and an adjoining military base to service American military transport planes destined for battlefronts in the Mediterranean and Southeast Asia. But protecting Liberia was also a priority. Thousands of African American troops, and a smaller contingent of white officers and soldiers, had been sent to secure a valuable American supply of natural rubber in a world at war. This era of American empire is over, but its legacy lingers. Standing next to the old Roberts International Airport terminal is a shiny new terminal of glass, concrete, and steel, its $50 million cost financed by Chinas Export-Import Bank. Recently opened, it resembles, with a dual cantilevered roof, the wings of a jumbo jet and signifies the rise of a new era of geopolitics and resource extraction in Africa.

Less than a mile away is the main entrance gate to Firestone Liberia. The company is now operated by the Tokyo-based Bridgestone Corporation, which acquired U.S.-based Firestone Tire & Rubber Company in 1988, almost a decade after the last Firestone to manage the family company gave up control. In 1926, the Liberian government granted a concession for up to a million acres of land to Harvey Firestone Sr. to build what would become the worlds largest contiguous rubber plantation. The territory that the Akron, Ohio, tire manufacturer initially claimed, as well as that on which Roberts Field was built, was once customary land of the Bassa people. They are one among a number of ethnic groups that settled in this region long before immigrantsfirst from America, and later the Caribbeanbegan arriving in the early nineteenth century to make this land their home.

Looking upstream from the Farmington Hotel, I catch a glimpse of a silver-hued water tower that marks the location of the Firestone latex-processing plant, originally built in 1940. Now, in an area covering roughly two hundred square miles, tappers awake early each morning, as they have done for generations, to extract the milky white fluid from millions of Hevea brasiliensis trees. Thousands of gallons of the liquid latex are transported by truck each day from the many divisions of the plantation to the factory. The smell of ammonia in the processing plant can be overpowering, as I learned when I too carelessly bent down to sniff the fast-moving latex flowing through the plant and was almost knocked unconscious. For decades, the Firestone Plantations Company used the Farmington River as a convenient sink for dumping ammonia and other waste products generated in the industrial production of natural rubber. Residents of nearby communities along the river who bathe, wash clothes, and fish in its waters had long complained of foul-smelling air, contaminated wells, skin rashes, and a scarcity of fish. But not until 2008 was a wastewater treatment plant built, almost seventy years after the factory began processing latex.

Atop a hill in the distance, not far from the old headquarters main entrance gate, sit the ruins of a two-story, reddish-orange brick house, its design out of keeping with the cinder block and mud brick homes in the area. I recognize it as the distinctive architectural style that Firestone used in constructing comfortable homes for its largely Americanand exclusively whitemanagement staff. Palm trees tower over the building. The surrounding landscape is bare but for recently planted rubber seedlings. Ruins like this one, found throughout the Firestone plantation complex, recall the plantation landscape of the antebellum South, where planters looked out over their property: land, crops, and human chattel. These hilltop homes assigned to white planters, as Firestone called its division superintendents, were purposefully separate from division camps, often located in low-lying areas and swamps, where an African labor force lived. A home on a hill offered some protection from the bite of the female Anopheles mosquito, which avoids higher elevations. The mosquito, an important link in the life cycle of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum, was a threat to the health and productivity of Firestones workers and remains so for workers today.

A few miles down the road from the Farmington Hotel, in the direction away from the Firestone plantations, another aspect of the expansive reach of an American rubber empire comes into view. The buildings of the Liberian Institute for Biomedical Research are also constructed in the Firestone style. In the entrance hallway is a gold plaque commemorating Harvey Firestone Sr. The laboratory complex was erected in 1952 with a $250,000 gift from Harvey Firestone Jr. to establish an institute for research in tropical medicine to honor his fathers deep and abiding faith in the Liberian people and commitment to their well-being.

In an outside part of the complex, empty cages, with rusting iron bars, and several painted concrete statues of chimpanzees evoke a time when both animals and humans were enrolled in experiments and clinical trials. Here, Western doctors and biomedical researchers sought treatments to combat malaria, schistosomiasis, and other tropical diseases that threatened the transformation of nature on an industrial scale. From the beginning of Firestones venture in Liberia, the beneficence of American science and medicine, in improving the lives of a Liberian workforce, could go far in winning support for an American rubber empire in a sovereign Black republic. The fragments and remains of that empire, centered on a plantation, are everywhere around me. An industrial ecology, built to satiate Americas growing thirst for rubber at the dawn of the automobile age, reordered relationships of life and land in Liberia. These fragmentary remains give clues to past worlds remade and new ones born.