Introduction

This book has a protagonist most readers will likely never have heard of. His name is Georg Handsch. He was born in 1529 in Leipa, todays eska Lipa, a small prosperous town approximately eighty kilometers north of Prague. He would return to this town shortly before his death in February of 1578. On his lifes journey, which led him from Leipa to Goldberg, Prague, Padua, and finally Innsbruck, he collected a number of achievements. He studied medicine in Padua and earned his doctoral degree in Ferrara. Though not as their equal, he was in the company of some of the famous scholars and physicians of his time, including Matthaeus Collinus, the figure-head of the Bohemian humanism, and the well-known physician and botanist Pietro Andrea Mattioli. In the end, probably thanks to the advocacy of Mattioli, he gained the position of court physician for the Habsburg Archduke Ferdinand II.

Handsch remains a largely unknown figure, even among medical historians.

Fig. 1: Joris Hoefnagel, Innsbruck with the castle of Ambras (after Alexander Colin), in: Civitates Orbis Terrarum, part 5, Cologne 1598, n58.

Not least of all, this is due to the lack of suitable sources. It is only in rough outlines that we can reconstruct the working life of physicians from the medical publications of the time. And as opposed to later periods, personal notes, diaries, practice journals and similar sources that could give us more detailed insights into physicians everyday medical practice during this period are scarce.

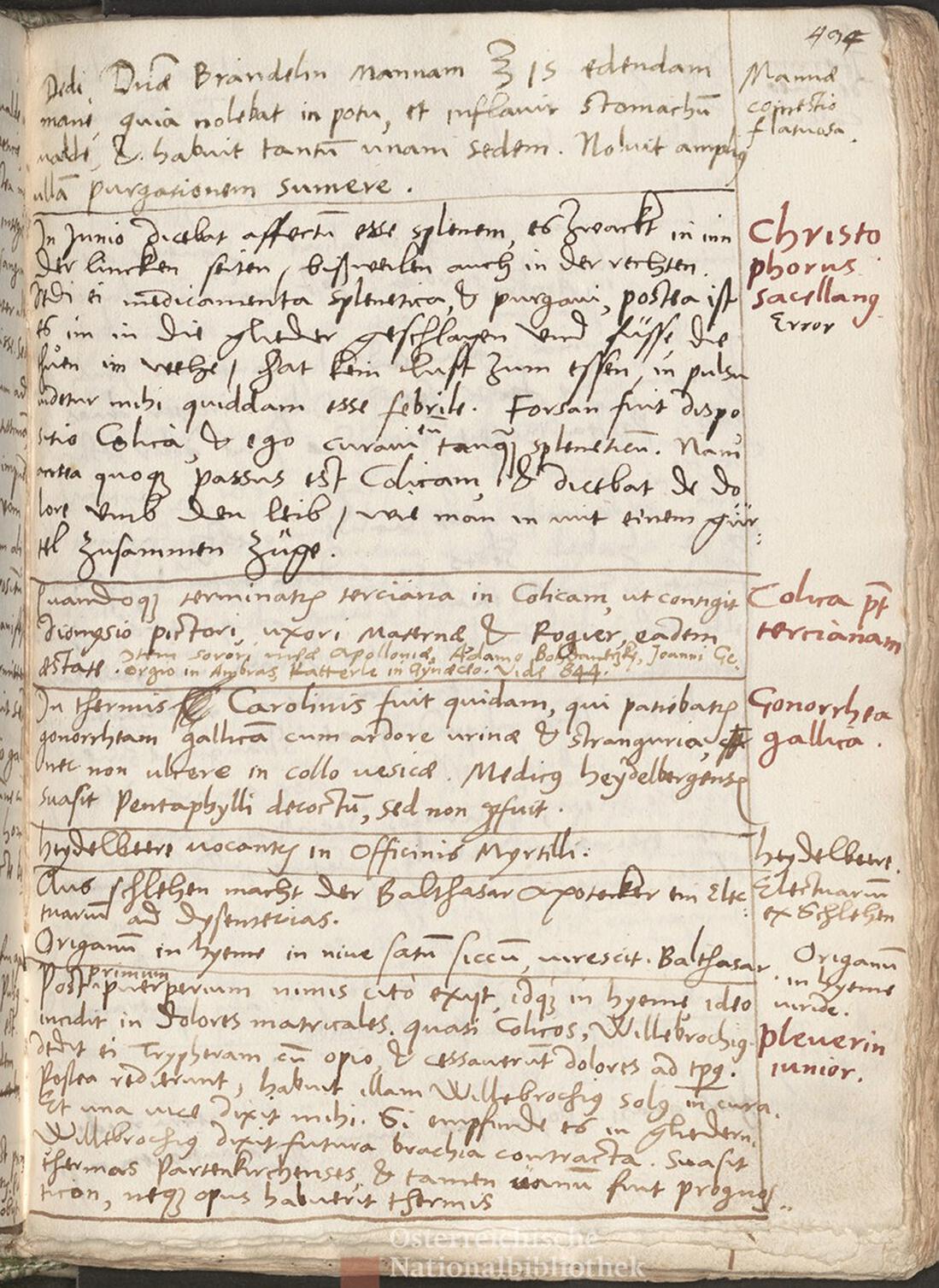

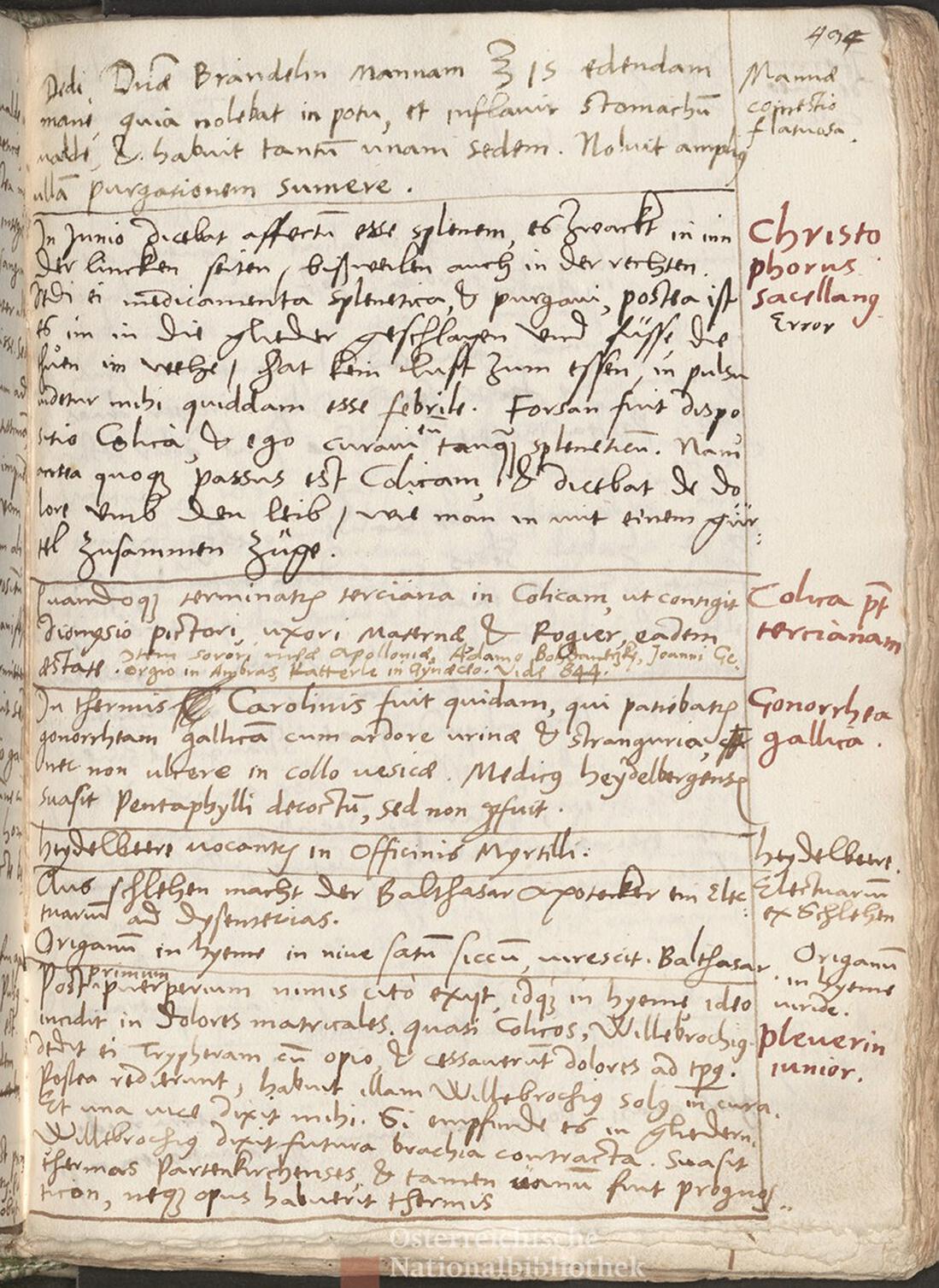

This brings us to the central reason for making Georg Handsch, as historically insignificant as he may be, the protagonist of this book: Handsch liked to write. He wrote a lot a whole lot in fact and much of what he wrote has survived. Close to thirty manuscript volumes from his pen, some of them counting more than a thousand pages, have been preserved in the Austrian National Library in Vienna. witnessed as a student are found next to entries relating diagnostic and therapeutic observations and experiences. Without any transition, the remarks of medical colleagues about the healing power of certain plants or the value of particular diagnostic signs are followed by notes about things he heard from barber-surgeons and lay healers or from patients and other laypeople. Not least of all, Handsch described countless clinical cases that his teachers in Prague and Padua dealt with as well as many others which he himself and his colleagues later treated in and around Prague and Innsbruck. In this way, his notebooks came to contain not only his own experiences and observations vis--vis his patients but also those of a whole array of famous and lesser-known colleagues around him.

For the most part, Handschs entries are very short. Frequently they extend, at best, over half a dozen lines. Much more rarely, he went into some detail on certain topics or traced the course of a persons disease as it unfolded day by day. Some of his notebooks also contain striking other elements. In hundreds of entries, Handsch recorded verbatim, mostly in German, the terms and expressions used by physicians to explain a medical condition to patients and their families. And again and again, the notes give patients and their relatives a voice in the notes, relating their ideas about the disease process, their desires and demands, as well as their perception of the medical treatment.

What makes Handschs notebooks all the more valuable is that they were clearly intended only for his personal use and not written with an eye to publication. Apart from several lectures he transcribed and his accounts of anatomical demonstrations, his entries are for the most part unsystematic and disorganized. Handsch simply wrote down, more or less on a daily basis it seems, what he heard and saw, learned and experienced as it happened. Some of it was clearly not intended for the eyes of others. With unsparing candor, he regularly referred to mistakes and errors he and his colleagues made in diagnosing and treating illnesses and in dealing with patients. Quite often, he even highlighted these entries in the margin, with words like error or errores mei. time when same-sex sexual contact was considered a serious sin and offence, he would have had to fear grave consequences if this had become known.

Handsch did not offer an explicit explanation of what drove him to fill one notebook after the other with many thousands of entries. Despite some very personal entries, it would be rather far-retched to interpret them as evidence of the frequently invoked rise of the individual during the Renaissance period.

The fact that Handschs notebooks have survived at all is thanks to a concurrence of circumstances, fortunate for historical research but less so for Handsch and his heirs. Having experienced a severe weakness of the body in 1576,

I discovered Handschs notebooks while carrying out systematic research on early modern medical manuscripts in the Austrian National Library. A look at the older literature in the field quickly revealed, however, that the existence of these notebooks had long been known to historians who were researching the court of Archduke Ferdinand II. More than a century ago, Josef Hirn praised them as a rich source for knowledge about the culture and courtly life of their time. remaining extensive handwritten texts from Handschs Nachlass, is inevitably very time-consuming, even for someone who is well-versed in the material. The benefit, meanwhile, is anything but certain. As mentioned, Handschs notes are often a motley jumble of more or less brief entries. Someone who wishes to make reliable generalizing statements about what Handsch knew or experienced concerning a particular illness or medication, for instance, would have to do what I did and read the notebooks in their entirety, collating dozens, or in some cases even hundreds, of entries made by Handsch on different occasions about the same subject.

Fig. 2: Page from one of Georg Handschs notebooks (sterreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna, Cod. 11183, fol. 434r).

For historians, however, who are interested not only in the great medical theories but also in their application who seek to uncover the everyday experience and practice of Renaissance physicians, their life-world and self-conception, their relationships and interactions with patients and their families, with less learned medical practitioners, and with the medical culture in general of early modern learned medicine in all its diversity there is more than a great challenge to be found in this colorful miscellany. The variety, the concreteness, and the closeness to everyday life are also what makes this source uniquely valuable and appealing. Handschs notebooks give a wealth of insights into the world of learned medicine and show how young men were introduced to it and they paint a uniquely multi-facetted picture of everyday medical practice in the town and in the country, of the encounters between physicians and patients, of physicians and laypeoples ideas about illness and how they approached it in everyday, practical ways. This picture is far richer and more detailed than that offered by the mostly printed sources on which most historical research in this area has so far had to rely.

So Georg Handsch and his singular notebooks are at the center of this book. This is definitely not a biography, however. In passing, I will also sketch out Handschs professional career and fill in some details about his life.

In methodological terms, this book links micro-historical and historical anthropological perspectives with praxeological approaches. Micro-history and historical anthropology these are two largely overlapping approaches have become established and widely acknowledged over the past decades. Their emphasis is on the life and culture of ordinary people, of the common folks. Seeking to reconstruct historical realities in all their diversity, however, with the explicit inclusion of the perspective of contemporary actors, researchers have long applied micro-history and historical anthropology to social, political, and intellectual elites as well.