The Other Side of Polyandry Property, Stratification, and Nonmarriage in the Nepal Himalayas

Women in Cross-Cultural Perspective Series

Sue-Ellen Jacobs, Series Editor

This new series presents ethnographic case studies that address theoretical, methodological, and practical issues in basic and applied fieldwork; it also includes cross-cultural studies based on secondary sources. Edited by Sue-Ellen Jacobs, the series makes a substantial contribution to our knowledge about the varieties and commonalities of women's experiences. One important focus of the series is on women in development and the effects of the development process on women's rotes and status. By considering women in the full context of the cultures, this series offers new insights on sociocultural, political, and economic change cross-culturally.

The Other Side of Polyandry

Property, Stratification, and Nonmarriage in the Nepal Himalayas

Sidney Ruth Schuler

First published 1987 by Westview Press, Inc.

Published 2019 by Routledge

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1987 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Schuler, Sidney.

The other side of polyandry.

(Women in cross-cultural perspective series)

Includes index.

1. Marriage--Nepal. 2. Single women--Nepal--Social conditions. 3. Polyandry--Nepal. I. Title. II. Series.

HQ728.S355 1987 306.8'1'095496 87-29593

ISBN 13: 978-0-367-29463-2 (hbk)

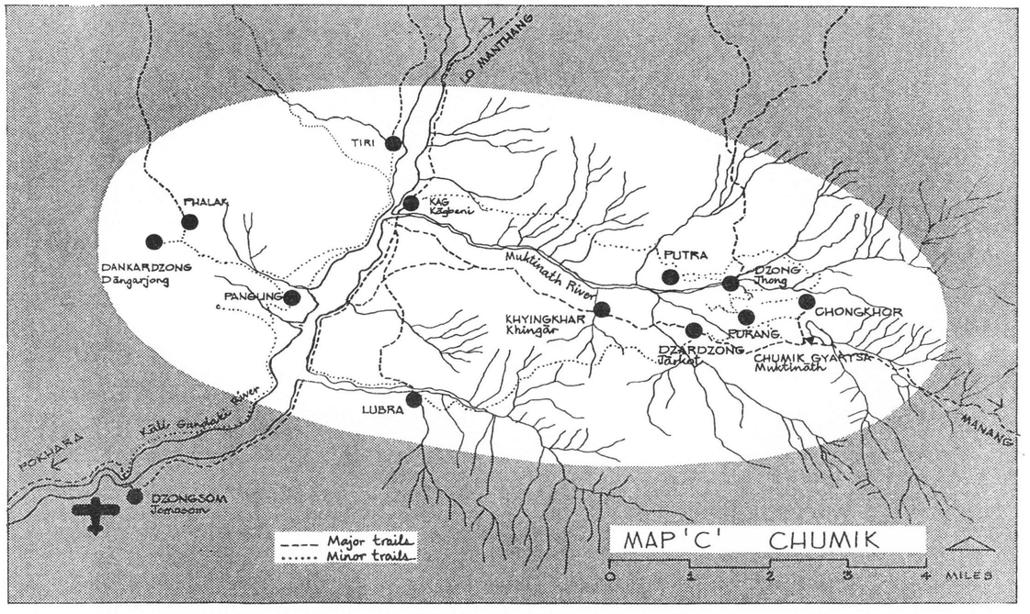

To my parents and to the people of Chumik

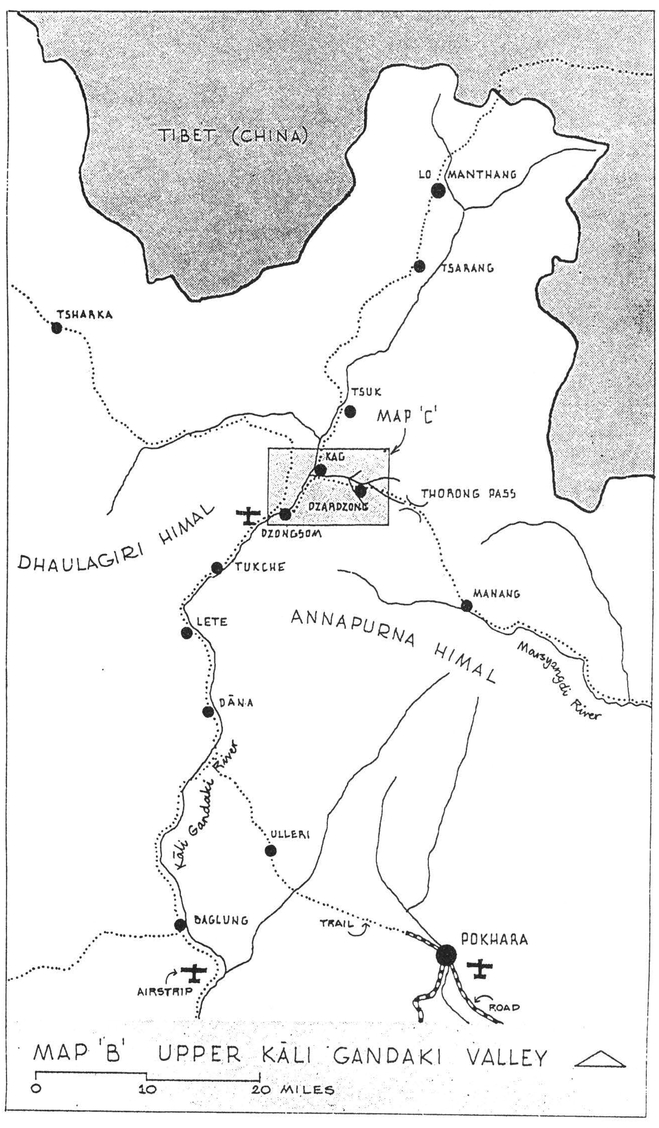

First of all, I thank all of the people of Chumik who befriended and assisted me. I am grateful to David Doberelner for his companionship during my field research, and for drawing the maps. I am also grateful to Prem Raj Gautam, former Chief District Officer of Mustang, and to the members of the Status of Women in Nepal Project and other fellow scholars working in Nepal for the ideas that emerged through discussions with them. Special thanks to Gabriel Campbell and Lynn Bennett, who helped me in many ways.

I am indebted to Tribhuwan University for sponsoring my research in Nepal, particularly to the Centre for Nepal and Asian Studies and two of its former directors, Dr. Prayag Raj Sharma and Dor Bahadur Bista. The research was funded by the Social Science Research Council, with a supplementary grant from the National Science Foundation.

I am grateful to my academic advisor, Nur Yalman, for many years of guidance and support, to Mel Goldstein and Ted Riccardi Jr., and to S.J. Tambiah and other faculty and graduate students at Harvard who commented on earlier drafts and sections of this study, particularly John Whiting, Bea Whiting, Jane Guyer, Dan Rosenberg, Monique Djokic, Emily McIntyre, and Martin Etter.

Additional thanks are due to Augusta Molnar for her valuable comments, and to Roy Jacobstein, my mother and sister, Cathy Gleason, and Dan Rosenberg who helped me to prepare the book for publication.

Sidney Ruth Sahulev

Although large numbers of unmarried adults are a common phenomenon in the modern industrial societies of the West, early and universal marriage has prevailed in non-Western societies, in traditional societies generally, and especially in South Asia. The origin of the so-called "European pattern," characterized by late marriage and a high proportion of people who never marry (Hajnal, 1953a, 1953b, 1965), Is not fully understood. To the extent that it occurs in non-European societies it tends to be associated with economic modernization, but there is strong evidence to suggest that the pattern is not simply a consequence of modernization. Frequent abstention from marriage was common in much of Northern and Western Europe well before the Industrial Revolution, from the first half of the 18th century, or even earlier, through the course of some two hundred years (Hajnal, 1965: 112-113). Furthermore, with the "marriage boom" following World War II, the European pattern began to disappear in the West (Hajnal. 1953b: Dixon. 1966:41-42).

There is evidence that in some societies late marriage and nonmarriage occur as a response to economic and demographic pressures. High rates of nonmarriage in Ireland after 1840, for example, and late marriage during the first half of the 20th century in Japan, apparently are associated with the efforts of families to increase agricultural productivity by consolidating landholdings and limiting subsequent division by means of primogeniture. Marriage was difficult for those without access to patrimonial land (Goode, 1963; Hajnal, 1965; Dixon, 1978). Clearly, however, since the economic and demographic squeeze is even more severe in much of Asia than it was, for example, in Ireland following the potato famine, historical and inter-societal variations in timing and incidence of marriage require a fuller explanation.

To a great extent demographic patterns reflect processes beyond the control of the individual. At the same time they are the outcome of individual and family decisions, decisions that take place within a nexus of perceived options and constraints, within a particular social context. This is particularly true of marriage patterns as opposed, for example, to patterns of mortality. The ability of historical demography to uncover the social contexts in which nonmarriage occurs is of course limited by the fact that it must rely on reconstruction, and in the contemporary world traditional societies with high incidences of nonmarriage among adults, and particularly women, apparently are rare. In any case the phenomenon has not been well described in the context of functioning social systems.

When the present study was conceived there was some evidence that the populations of remote, high altitude Tibet and the Tibetan societies of the Himalayas represent an exception to the traditional and non-Western pattern of early and nearly universal marriage. Recent studies had revealed the existence of substantial numbers of unmarried women in several small Tibetan societies in the Himalayas of northwestern Nepal (Goldstein 1974, 1975, 1977a, 1977b; Levine 1977, Ross 1981). In Limi, for example, in the small Tibetan village studied by Goldstein (1976:223-233) where 38 percent of the marriages recorded were polyandrous, 20 percent of the women 35 years of age and above had never been married. The focus of their research being the effect of fraternal polyandry on aggregate levels of fertility, Goldstein and later Levine and Ross treated nonmarriage among women simply as a product of fraternal polyandry; they did not investigate nonmarriage as a phenomenon in itself.