LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS MONOGRAPHS ON SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGY

Managing Editor: Charles Stafford

The Monographs on Social Anthropology were established in 1940 and aim to publish results of modem anthropological research of primary interest to specialists.

The continuation of the series was made possible by a grant in aid from the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research, and more recently by a further grant from the Governors of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Income from sales is returned to a revolving fund to assist further publications.

The Monographs are under the direction of an Editorial Board associated with the Department of Anthropology of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

First published 2004 by Berg Publishers

Published 2020 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

605 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

H. Ian Hogbin 2004

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

ISBN 13: 978-1-8452-0000-8 (hbk)

Preface

I WISH to express my thanks to Professor J. A. Barnes, Dr M. J. Meggitt, Dr C. Jayawardena, and Mrs W. M. Balding, each of whom read and criticized parts of the MS of this book.

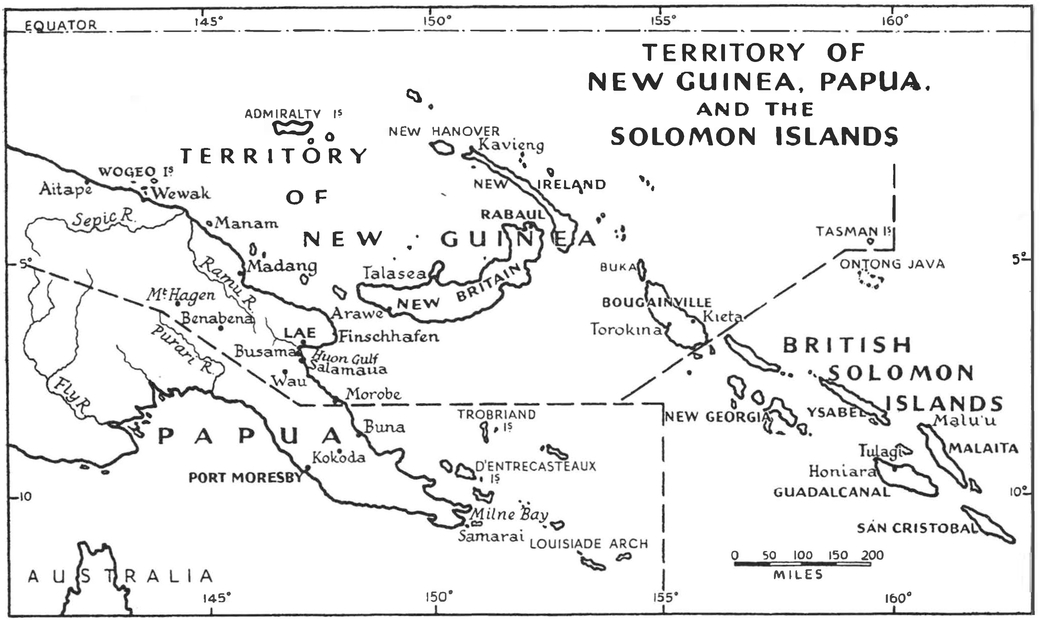

The work was finished in 1960, and the delay in publication has been beyond my control. Had I been writing the concluding sections of now I would not have lumped all non-unilineal systems together. Certainly they have facton in commo n, but there are also important di1ferencea. Am ong the To'ambaita of Malaita a man is free to choose his district group, and am ong the Buaama he can choose his club group. In Malaita, however, the limiting factor is still descent, as in societies with a unilineal systemalthough the descent is not restricted to a single line whereas in Busama descent does not enter into the situation. Here the limiting factor is the existence of a relationship tie, which may be genealogical or affinal, with some person already accepted as a member of the desired group.

I. H.

Department of Anthropology

University of Sydney

19 March 1962

1

The Setting

AN earlier publication of mine, Transformation Scene, dealt with changes in the economic organization, political system, legal code, and religious beliefs of the people of the New Guinea settlement of Busama during half a century of European contact. The present volume is a companion study concerned primarily with the kinship structure, which, in contrast, has survived almost unaltered. I shall begin with a brief general description and proceed to a detailed account of the different groupings and relationships of the members. Then I shall give the life history of an average native from birth through infancy, childhood, adolescence, and marriage to maturity and in the process show how the community gradually tightens its grip.

Busama ia situated on the western shore of the Huon Gulf. Germany had annexed the whole north-eastern quarter of New Guinea in 1884, but the Gulf region did not come under full administrative control till after 1900. An Australian Force drove the Germans out in 1914, and since that date, except for the period 1943-4, when the Japanese Army was in possession, the country has been ruled by Australia, after 1921 under Mandate from the League of Nations, more recently as a Trust Territory of the United Nations. The Government station for Busama is at Lae, less than twenty miles away by canoe to the north. Certain native residents act as permanent official representatives, known as the 'luluai' and the 'tultul', and from time to time European officers carry out patrols.

German Lutheran missionaries were on the scene by about 1907 and set up a local headquarters four miles to the south at a place called Mala'lo. Soon all the Busama were Christians. They built village schools for the Mission, and here the children learned reading and writing. American missionaries replaced the Germans in 1946.

By 1907 the males had already begun seeking employment as wage labourers on the coconut plantations that white settlers were establishing on the neighbouring islands of New Britain and New Ireland. The youths departed at the age of sixteen or seventeen and mostly came back in time to marry six years later. Then in 1926 gold was discovered in the hinterland. This led to the opening up of a deep-water port, Salamaua, a couple of miles beyond Mala'lo and subsequently to the establishment of an aerodrome at Lae. Native workers were in keen demand on the goldfields and

in the two towns, and many men preferred to spend their term of service closer to home. Salamaua was destroyed during the bombing raids of 1944 and has never been rebuilt. The European and Asian population of Lae, however, has gone on increasing. At present it exceeds 3,000.

Like the other Pacific islanders, the Busama are horticulturalists. Their staple food is taro, and they also plant yams, sweet potatoes, and green vegetables, a few fruits (the banana is the most important), and coconuts. Sago provides additional carbohydrate, but the palms grow wild in the swamps and require no special attention. Animal protein comes from the domestic pigs and chickens, from such game as wild pigs and bandicoots, and from fish. These last the people catch by a wide variety of methodswith spears from the shore and, in canoes, with baited hooks, lures, poison, hand nets, and heavy seines.

THE VILLAGE

When I first reached Busama, in 1944, there were about 600 inhabitants. They were then living in a forest clearing whither they had retreated during the fight for Salamaua and Lae. Not for another year, when, at the end of the war in the Pacific, the Civil Administration was restored, did they go back to the proper site on the coast.

The reconstructed village is now in outward appearance much as it used to be. It stands on a narrow shelf of flat land between the beach and a row of steep jungle-clad cliffs. At two points the high ground advances across the shelf towards the sea and forms a pair of headlands. One of these, un-marked on the charta, forms the southern boundary, and only the cemetery is on the far side. The other, known to Europeans as Schneider Point (Ho'tu to the natives), is approximately in the centre. In the olden days these promontories could each be successfully defended by a handful of warriors, and the original settlement was confined to the strip in between. The name Busama, or Bu-samang in its correct form, is actually that of a spring at the base of one of the cliffs (