1

Death House Rendezvous

B Y 1980, New Jerseys notorious Death House had been revived as a lovers alcove, but Rubin Hurricane Carter still wanted no part of it.

The Death House was Trenton State Prisons official name for the brick and concrete vault where condemned men lived in tiny cells and an electric chair stood hard against a nearby wall. The first inmate reached the Death House on October 29, 1907. Six weeks later he was dead, his slumped body shaved and sponged down with salt water, the better to conduct the electricity. New Jersey continued to hang capital offenders for two more years. But soon enough the electric chair, with its wooden body, leather straps, and metal-mesh helmet, which discharged three mortal blasts of up to 2,400 volts, was seen as the most felicitous form of execution.

At least one infamous death gave the site a brief aura of celebrity. Richard Bruno Hauptmann, convicted of murdering Charles Lindberghs baby, was electrocuted in the brightly lit chamber at 8:44 P.M. on April 3, 1936. In later years, sentences were carried out at 10 P.M. , after the general population prisoners had been placed in total lockup. An outside power line fed the chair to ensure that a deadly jolt did not interfere with the penitentiarys regular lighting. On occasion, citizen witnesses crowded into a small green room, with only a rope between them and the chair about ten feet away. The observers watched the executioner turn a large wheel right behind the seated mans ear, thereby activating the lethal current. The body, penitent or obdurate, innocent or guilty, alive or dead, pressed against the restraints until the current was shut off.

The Death House confronted its own demise in 1972, when the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed the death penalty as cruel and unusual punishment. The electric chair, having singed the breath from 160 men, was suddenly obsolete. So prison officials found a new mission for the chamber: it became the Visiting Center.

Despite its macabre history, the VC was a huge hit with most of the prisoners. It marked the first time that Trenton State Prison, a maximum-security facility, had allowed contact visits. Inmates could now touch their spouses, children, or friends. The metal bars were removed from more than two dozen Death Row cells near the archaic chair, its seven electric switches still in place. The rooms were not exactly cozy hideaways, but they became the unsanctioned venue for conjugal meetings. Inmates seeking a bit of privacy tried to reserve cells farthest away from the guards, and the arrangement, as described by some oldtimers, gave rise to Death House babies.

But Rubin Carter didnt care a bit. He refused to accept virtually anything the prison offered, and that included visits inside the reincarnated Death House.

He was repulsed by the prospect of sharing an intimate moment among the souls of 160 men, some of whom he knew. Transforming this slaughterhouse into a visiting center, Carter believed, was like turning Auschwitz or Buchenwald into a summer camp for children. It was another way for the state to humiliate prisoners, to express its contempt for the new law that pulled the plug on its chair.

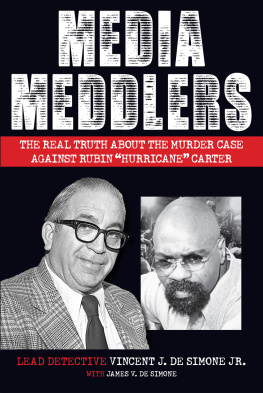

Carter knew well that he could have been one of the chairs immolations. In 1967 he had been found guilty of committing a triple murder in Paterson, New Jersey. He adamantly claimed his innocence. The state sought the death penalty, but the jury returned a triple-life sentence instead. That conviction was overturned in 1976, but Carter was convicted of the same crime again later that year and given the same triple-life sentence.

By the end of 1980, Carter had gone for almost four years without a contact visit. Since his second sentencing in February of 1977, he had not seen his son or daughter, his mother, his four sisters, or his two brothers. Most of his friends were also shut out. He and his wife had divorced. He saw his lawyers in another part of the prison.

But now, on the last Sunday of the year, Carter had a visitor as the result of an unusual letter hed received three months earlier. As a former high-profile boxer who was known around the country and even the world, he received hundreds of letters each year, but he rarely answered them. In fact, he didnt even open them, allowing them to pile up in his cell. Carter wanted nothing to do with the outside world.

Then came a letter in September, his name and prison address printed on the envelope. Carter could never explain why he opened it except to say that the envelope had vibrations. The letter, dated September 20, 1980, was written by a black youth from the ghettos of Brooklyn who, oddly enough, was living in Toronto with a group of Canadians. The seventeen-year-old, Lesra Martin, wrote that he had read Carters autobiography, The Sixteenth Round, written from prison in 1974, and it helped him better understand his older brother, who had done time in upstate New York. Lesra concluded the letter:

All through your book I was wondering if it would have been easier to die or take the shit you did. But now, when I think of your book, I say if you were dead then you would not have been able to give what you did through your book. To imagine me not being able to write you this letter or thinking that they could beat you into giving up, man, that would be too much. We need more like you to set examples of what courage is all about!

Hey, Brother, Im going to let it go. Please write back. It will mean a lot.

Your friend,

Lesra Martin

Lesras words, his efforts to reach out, touched Carter. He responded on October 7. The one-page typewritten note thanked Lesra for his outpouring of hope, concern and humanness... The heartfelt messages literally jumped off the pages.

More letters followed between Lesra, his Canadian guardianswho had essentially adopted the youth to educate himand Carter in which they discussed politics, philosophy, Carters own case, and his appeal. But when Lesra asked if he could visit the prison at Christmastimehe was going to be in Brooklyn seeing his familyCarter replied noncommittally. That did not deter Lesra. The bond between the twoand, more important, between Carter and this mysterious Canadian commune that typically shunned friendships with the outside worldhad been sealed.

Winters chill could be felt inside the Trenton State Prison on that last Sunday of December. Built in 1836 by the famed British architect John Haviland, the prison is a brooding, monolithic fortress. Haviland used trapezoidal shapes and austere giganticism to evoke a massive Egyptian temple. Scarab beetles, which symbolized the soul in ancient Egypt, were carved into the prisons pink limestone walls. Tributaries from the Delaware River flowed in front of the prison, in faint mimicry of the Nile.