CHAPTER I.

Farewell To My Native Land.

"The web of our life is of a mingled yarn, good and ill together; our virtues would be proud if our faults whipped them not, and our crimes would despair if they were not cherished by our virtues."

Shakespeare.

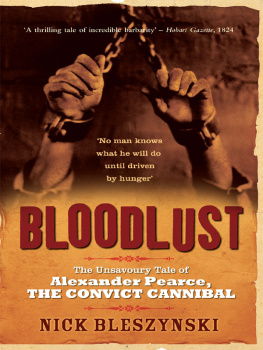

I was born at Shoreditch, near London, on the 28th of May, 1819, and was nearing the age of sixteen when one day I was accused of committing a paltry theft. Of this I was innocent, and naturally denied it, but the constable who accosted me insisted, no matter what I said, that I had to go with him. My feelings were anything but high-flown as I passed along the street with himwhat boy's feelings would be?on the other hand they were down almost below zero. It was no use; I soon realised my position, it was this:If I am found guilty of this offenceand I have little hope of proving my innocenceHeaven only knows where I may find myself. My trial came on before a Bench of Magistrates in Worship Street, London, on July the 3rd, 1834, and I was committed to take my trial. When a man had the bad luck to get committed, he was sent to Clerkenwell, or to the Old Bailey, and if he listened to the conversations of his associates at either of these places, during intervals that he might be remanded, it was quite possible that a previously innocent man would be converted into an adept at picking pockets and house-screwing. I was a new-chum in places of this kind, and also at such pursuits. New-chums generally fell into, and were made the subject of, numbers of practical jokes, too, at the hands of these fellows, and I was saved none the less in this respect. "Go upstairs and get the bellows," one of them said to me: and when I got to the top of the stairs, some others sent me to the far end of the ward for it. On arrival there, another crowd met me with knotted handkerchiefs, and 'pasted' me all the way back. "Pricking a crow's nest," was another of their games. This consisted in making a round ring on the wall with a piece of charcoal, and placing a black dot in the centre of it. One was then blindfolded, and his object was to place his finger on this black dot; but instead of doing this, another fellow stood with open mouth to receive the finger, and he didn't forget to bite it either. If anyone took money into this place they might as well say 'au revoir' to it, for they were not asleep. After a few days of this life my trial came onI was sentenced to Australia for 7 years' penal servitude. Then I was sent to Newgate, and when the door opened there, I was met by a large number of "Jack Shepherds," all in irons, and the place was as dismal-looking as the grave. First I entered the receiving-room, and remained there a day; afterwards I was put in with a fine assemblage of characters, and one might as well begin to count the stars in the Heavens as attempt to define who was the worst individual there. Night came on and I began to look around for a bed; this I found consisted of a rug and a mat, of which I availed myself. If a man was sentenced to seven years he was only kept there for a few days, and was then taken in irons, by means of a van, to the "hulk" at Portsmouth. This was the fate I shared. On arrival there I was stripped of my clothes, and after the barber came round and cut my hair so close that it was only with difficulty I could catch hold of it, I was washed from two tubs of water which stood close by. Then I was dressed in a pair of knee breeches, stockings, shirt, and a pair of shoes so large that I could have almost crossed the Atlantic in them, and a hat capable of weathering the greatest hurricane that ever blew. Whilst on board the hulk an old Jew paid several visits, for the purpose of buying up all the ordinary clothes of the men, and no matter how new a suit might be, it was either a matter of take half-a-crown for it or throw it away. Fortunately, my best clothes were left behind, and I lost nothing by this.

I remained on the hulk from Friday till Monday morning, and was then transferred to what was known as the Bay Shipthe "Hoogly"by means of a cutter. There were 260 prisoners on board this ship altogether. Before leaving the hulk, the irons worn in Australia were attached to the legs, but these were removed on getting to sea. Men, however, were branded all overshirt, trousers, and everything else. The "Hoogly" left Portsmouth harbour on the 28th July, 1834, and was 120 days coming to Australia, and the passage on the whole was not unfavorable. Four men, however, were flogged during the passage for misconduct. One of those on board was transported for stealing articles from a Roman Catholic Chapel, and he had by some means managed to get a quantity of tobacco into his possession. One night whilst he was asleep some of the others conspired to get this tobacco, and they put his big toe into the bunghole of a cask. He used to sleep on the tobacco, and as soon as he sat up to release his toe the tobacco was passed away through the crowd, and that was the last he saw of it.

CHAPTER II.

Arrival at Sydney.

"Misery acquaints a man with strange bedfellows."

Shakespeare.

Notwithstanding the fact that the Settlement at Sydney was now nearly 50 years old, my impression on arriving there in the summer of 1834 was anything but a bright one, and by no means came up to my faintest expectations. It was a scattered-looking placea house here and a terrace there, but miserable enough to my mind. After we had been in Sydney harbour a few days, a number of officials came aboard the ship, and, as if 'to the manner born,' took a list of the marks on the men, who were stripped to the waist. One of them, in particular, had some writing on his arm, and he was told that if it was not quickly removed, he would get 50 lashes for it when he reached shore, so he took the advice. We remained aboard ship till three days later, we were marched ashore in line, four deep, a little after daylight, and taken to Hyde Park Barracks. Here we got a beautiful breakfast, "hominy," in little tubs. At 2 o'clock the same day we were called out to witness a punishment. There were no "25's" there; all "50's" and "75's"goodness knows what the offenders had been doing. After this, it was possible for any one of us to be called out and sent to a master. If a man had a seven years' sentence, he had to serve four years with a master before he got a "ticket-of-leave;" but if he happened to prove himself a success at any particular vocation, he would never get his "ticket," as the master for whom he was working would arrange with one of the other servants to quarrel with the handy man, and he would be sent to the lock-up to be flogged, and get an addition to his sentence. If a man was sentenced to 14 years, he had to serve 6 years with a master before he got a "ticket." All the master had to give a servant in the year was 2 suits of clothes, 2 pairs of boots and a hat, also his food. The latter was supposed to be either 3 lbs. of maizemeal and 7 lbs. of flour, or 9 lbs. of beef for the week.