French Symbolism:

Objectifying the Subjective?

by

James Longford

In an interview in LEcho de Paris , 1891, Stphane Mallarm complained: Is there not something abnormal in the certainty of discovering, when opening any book of poetry, uniform and agreed-upon rhythms from beginning to end, even though the avowed goal is to arouse our interest in the essential variety of human feelings! Where is inspiration? Where the unforeseen? and how tiresome! In his comments on poetry, Mallarm laid out some of the aims of Symbolism in art too.

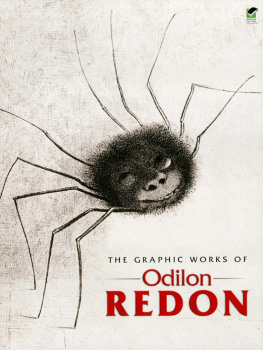

In this essay I am going to discuss the origins of the Symbolist Movement in France in the second half of the nineteenth century, its objectives, and the place of three key artists, Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon and Paul Gauguin, within the movement. For reasons of space, I am not going to consider in detail the overlapping and related movements such as the Salon de la Rose+Croix.

Symbolism in France developed in the second half of the nineteenth century against a background where Realism and Impressionism were prevalent in art and Naturalism in literature. As a movement, Symbolism had literary roots, particularly in poetry, and in that respect it was similar to Romanticism. Indeed, Edward Lucie-Smith argued that, from a historical perspective, Symbolism can only be viewed as a part of the Romantic Movements rejection of the idea that reason could solve all human problems. The implications of rejecting reason were profound. As he put it, the validity and authority of the objectively perceived world having been called into doubt, subjectivity inevitably triumphed. Men now looked within themselves for guidance.

That looking inwards also involved looking backwards, to the art of earlier eras which was seen as purer and more spiritual than the art of the nineteenth century and contrasted with the Naturalism and Realism that the Symbolists rejected. Renaissance art in particular contained a use of symbols that fascinated the burgeoning Symbolist movement. According to Renaissance philosophers, melancholy was a characteristic of the artist in whom imagination prevails while Reason was the preserve of the scholar.

Traditionally, the meaning of a symbol had been determined in advance, enabling a work to be read like a text, and the role of allegory and symbol had been mixed.

Symbols were also used extensively in Romanticism, for instance in Francisco Goyas The Colossus (or Panic ) (Oil on canvas, 1808-12, Museo del Prado, Madrid) and Caspar David Friedrichs The Cross in the Mountains (The Tetschener Altar) (1808, Fig. 3), where they are the principal elements in the composition, but in Romantic painting they tend to lack the level of ambiguity and mystery necessary to be called fully Symbolist. Nonetheless, it was the great Romantic painter Eugene Delacroix (1798-1863) that Charles Baudelaire would later draw upon in order to elaborate his theories of aesthetics that were so influential for the Symbolist Movement. In his Salon review of 1846, Baudelaire described Delacroix as using nature like a vast dictionary, whose leaves he flips

Symbolist ideas in France first began to coalesce with the publication of the novel A Rebours (Against Nature) by J.K. Huysmans in 1884, which through its hero, Jean Des Esseintes, praised the work of Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon. Esseintes is an exceptional individual rather than a downtrodden character from a Naturalist novel, and he rejects the banal so-called progress of the modern world in favour of a life of personal exploration. The character was based on an amalgam of Huysmans himself and the notorious dandy Robert de Montesquiou. The ideas in the novel were quickly associated with the Decadent Movement and also appealed to the developing Symbolist movement who similarly rejected the idea of inevitable human progress, and what they saw as the crude materialism and excessive moralism of recent years.

Huysmans followed up A Rebours with the 1891 L-bas ( Down There ), the first in a trilogy that followed the story of another character loosely based on Huysmans who also rejects the modern world in disgust and explores the world of modern Satanism before converting to Catholicism. Josphin Pladans, 1884 Le vice suprme , explored similar themes.

Symbolism as a movement was named by the poet Jean Moras in his 1886 Symbolist manifesto in Le Figaro . He abandoned it in 1891 but by then it had a life of its own and a powerful proponent in the form of poet Stphane Mallarm who was experimenting with the placing of words in poetry outside of their expected context as Symbolist painters were starting to do with symbols in their art. Mallarm said in 1891: To name an object is to suppress three-quarters of the enjoyment of the poem, which derives from the pleasure of step-by-step discovery; to suggest, that is the dream. It is the perfect use of this mystery that constitutes the symbol.

Another poet who embraced Symbolist ideas and was one of the decadents was Paul Verlaine who promoted musicality in his poetry at the expense of strict rhythm and rhyme. In his 1874 poem Art potique (The Art of Poetry) , written while he was in jail and only published 1882, Verlaine says in the first two lines: De la musique avant toute chose (Let music come first) and , Et pour cela prfre lImpair (And for this I choose an odd meter). In verse four he gives a short summary of the Symbolist approach to the arts:

Car nous voulons la Nuance encore,

Pas la couleur, rien que la nuance!

Oh! la nuance seule fianc

Le rve au rve et la flte au cor!

For we still want nuance,

Not color, nothing but nuance!

Only nuance affiances

Dream to dream and the flute to the horn!

The poem here echoes Delacroixs 1857 question: What is the point of sounding sometimes the flute, sometimes the trumpet? and Symbolisms close affinity with the world of music, as elaborated by Baudelaire, by suggesting that only vagueness and nuance can unite diverse elements in interesting ways.

Verlaine was just one of the group of mostly young literary figures who gave receptions, wrote articles, reviewed art and could be relied upon to promote the cause of the less literary painters that they adopted. Another was Albert Aurier (died aged 27) who in his 1891 essay Le Symbolisme en peinture: Paul Gauguin, laid out in detail the case for Symbolism in art. Aurier argued that the alternative to Realism was not a return to Classicism, which he termed Idealism, but Symbolism (Ideist art), the representation of the pure idea in art. Aurier acknowledged that great masterpieces had been produced by Realism, as well as many banal abominations such as the photograph, but he argued that any fair analysis had to show that ideistic art was purer and more elevated than Realism because of the superiority of ideas over matter. The Classicists indeed were like the Realists as the object of both was the representation of the material world and the cunning dressing up of ugly tangible things.

The objective of the Ideists, on the other hand, was to express the world of ideas using a special language. That language was the sign (Symbol) which, like Baudelaires description of Delacroixs vast dictionary, was a part of an enormous alphabet which only the man of genius knows how to spell.

It followed therefore that the vocabulary of the sign should be simplified (Synthetist) to make it easier for the layman to understand and that certain techniques of pictorial representation should be avoided, such as illusionism or trompe loeil , in order that the spectator should not be confused into thinking that an object in a picture was nothing more than it appeared to be. The job of the painter then was to be Subjective, to choose with discrimination only the lines, forms and colours that served to convey the ideistic meaning of an object and nothing more, in order to serve the greater ideistic purpose of the work.

Next page