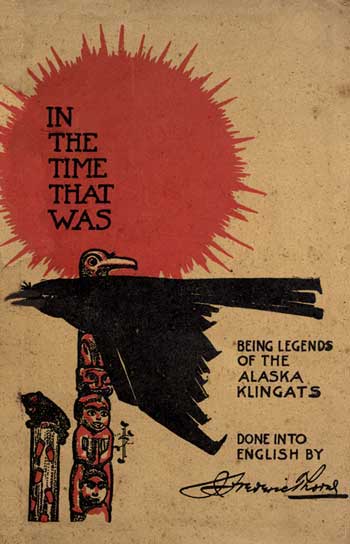

In the Time That Was

"And There Was Light."

achook of the Chilkats told me these tales of The Time That Was. But before the telling, he of the Northland and I of the Southland had travelled many a mile with dog-team, snowshoes, and canoe.

If the stories suffer in the telling, as suffer they must afar from that wondrous Alaskan background of mountain and forest, glacier and river, wrenched from the setting of campfires and trail, and divorced from the soft gutturals and halting throat notes in which they have been handed down from generation to generation of Chilkat and Chilkoot, blame not Zachook, who told them to me, and forbear to blame me who tell them to you as best I may in this stiff English tongue. They were many months in the telling and many weary miles have I had to carry them in my memory pack.

I had lost count of the hours, lost count of the days that at best are marked by little change between darkness and dawn in the Northland winter, until I knew not how long I had lain there in my blanket of snow, waiting for the lingering feet of that dawdler, Death, to put an end to my sufferings.

Some hours, or days, or years before I had been pushing along the trail to the coast, thinking little where I placed my feet and much of the eating that lay at Dalton Post House; and of other things thousands of miles from this bleak waste, where men exist in the hope of ultimate living, with kaleidoscope death by their side; other things that had to do with women's faces, bills of fare from which bacon and beans were rigidly excluded, and comforts of the flesh that some day I again might enjoy.

Then, as if to mock me, teach me the folly of allowing even my thoughts to wander from her cold face, the Northland meted swift punishment. The packed snow of the trail beneath my feet gave way, there was a sharp click of steel meeting steel, and a shooting pain that ran from heel to head. For a moment I was sick and giddy from the shock and sudden pain, then, loosening the pack from my shoulders, fell to digging the snow with my mittened hands away from what, even before I uncovered it, I knew to be a bear trap that had bitten deep into my ankle and held it in vise clutch. Roundly I cursed at the worse than fool who had set bear trap in man trail, as I tore and tugged to free myself. As well might I have tried to wrench apart the jaws of its intended victim.

Weakened at last by my efforts and the excruciating pain I lay back upon the snow. A short rest, and again I pulled feebly at the steel teeth, until my hands were bleeding and my brain swirling.

How long I struggled blindly, viciously, like a trapped beaver, I do not know, though I have an indistinct memory of reaching for my knife to emulate his sometime method of escape. But with the first flakes of falling snow came a delicious, contentful langour, deadening the pain, soothing the weariness of my muscles, calming the tempest of my thoughts and fears, and lulling me gently to sleep to the music of an old song crooned by the breeze among the trees.

When I awoke it was with that queer feeling of foreign surroundings we sometimes experience, and the snow, the forest, the pain in my leg, my own being, were as strange as the crackling fire, the warm blanket that wrapped me, and the Indian who bent over me smiling into my half opened eyes.

So were our trails joined and made one; Zachook of the Northland, and I of the Southland, by him later called Kitchakahaech, because my tongue moved as moved our feet on the trail, unceasingly. And because of this same love of speech in me, and the limp I bore for memory of the bear trap, for these and possibly other reasons, and that a man must have a family to bear his sins, of the Raven was I christened by Zachook, the Bear, and to the family of the Raven was I joined.

Orator among his people though he was, Zachook was no spendthrift of speech. But surly he never was; his silence was a pleasant silence, a companionable interchange of unspoken thoughts. Nor did he need words as I needed them, his eyes, his hands, his wordless lips could convey whole volumes of meaning, with lights and shades beyond the power that prisons thought. Not often did he speak at length, even to me, unless, as it came to be, he was moved by some hap or mishap of camp or trail to tell of the doings of that arch rascal, Yaeethl, the raven, God, Bird, and Scamp. And when, sitting over the fire, or with steering paddle in hand, he did open the gates that lead to the land of legend, he seemed but to listen and repeat the words of Kahn, the fire spirit, who stands between the Northland and death, or of Klingat-on-ootke, God of the Waters, whose words seemed to glisten on the dripping paddle.

So it was upon an evening in the time when we had come to be as sons of the same mother, when we shared pack and blanket and grub alike, and were known, each to the other, for the men we were. We had finished our supper of salmon baked in the coals, crisply fried young grouse and the omnipresent sourdough bread, and with the content that comes of well filled stomachs were seated with the fire between us, Zachook studying the glowing embers, I with that friend of solitude, my pipe, murmuring peacefully in response to my puffing.

As usual, I had been talking, and my words had run upon the trail of the raven, whose hoarse call floated up to us from the river. Idly I had spoken, and disparagingly, until Zachook half smilingly, half earnestly quoted:

"He who fires in the air without aim may hit a friend."

And as I relapsed into silence added: "It is time, Kitchakahaech, that you heard of the head of your family, this same Yaeethl, the raven. Then will you have other words for him, though, when you have heard, it will be for you to speak them as a friend speaks or as an enemy. Of both has Yaeethl many."

I accepted the rebuke in silence, for Zachook's trail was longer then mine by many years, and he had seen and done things which were yet as thoughts with me.

For the time of the smoking and refilling of my pipe Zachook was silent, then with eyes gazing deep into the fire, began:

"Before there was a North or South, when Time was not, Klingatona-Kla, the Earth Mother, was blind, and all the world was dark. No man had seen the sun, moon, or stars, for they were kept hidden by Yakootsekaya-ka, the Wise Man. Locked in a great chest were they, in a chest that stood in the corner of the lodge of the Wise Man, in Tskekowani, the place that always was and ever will be. Carefully were they guarded, many locks had the chest, curious, secret locks, beyond the fingers of a thief. To outwit the cunning of Yaeethl were the locks made. Yaeethl the God, Yaeethl the Raven, Yaeethl the Great Thief, of whom the Wise Man was most afraid.

"The Earth Mother needed light that her eyes might be opened, that she might bear children and escape the disgrace of her barrenness. To Yaeethl the Clever, Yaeethl the Cunning, went Klingatona-Kla, weeping, and of the Raven begged aid. And Yaeethl took pity on her and promised that she should have Kayah, the Light, to father her children.