Esther Singleton

The Shakespeare Garden

Published by Good Press, 2021

EAN 4066338072436

Table of Contents

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| Stratford-upon-Avon, New Place, Border of Annuals |

| FACING PAGE |

| Fifteenth Century Garden within Castle Walls, French |

| Lovers in the Castle Garden, Fifteenth Century MS. |

| Garden of Delight, Romaunt of the Rose, Fifteenth Century |

| Babar's Garden of Fidelity |

| Italian Renaissance Garden, Villa Giusti, Verona |

| John Gerard, Lobel and Parkinson |

| Nicholas Leate |

| The Knot-Garden, New Place, Stratford-upon-Avon |

| Typical Garden of Shakespeare's Time, Crispin de Passe (1614) |

| Labyrinth, Vredeman de Vries |

| A Curious Knotted Garden, Crispin de Passe (1614) |

| The Knot-Garden, New Place, Stratford-upon-Avon |

| Border, New Place, Stratford-upon-Avon |

| Herbaceous Border, New Place, Stratford-upon-Avon |

Carnations and Gilliflowers; Primroses and Cowslips;

and Daffodils: from Parkinson |

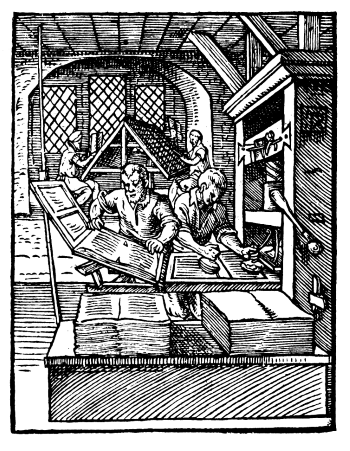

| Gardeners at Work, Sixteenth Century |

| Garden Pleasures, Sixteenth Century |

| Garden in Macbeth's Castle of Cawdor |

| Shakespeare's Birthplace, Stratford-upon-Avon |

| Elizabethan Manor House, Haddon Hall |

| Rose Arbor, Warley, England |

Red, White, Damask and Musk-Roses; Lilies and Eglantines

and Dog-Roses: from Parkinson |

| Martagon Lilies, Warley, England |

| Wilton Gardens from de Caux |

| Wilton Gardens To-day |

| A Garden of Delight |

| Sir Thomas More's Gardens, Chelsea |

| Pleaching and Plashing, from The Gardener's Labyrinth |

| Small Enclosed Garden, from The Gardener's Labyrinth |

| A Curious Knotted Garden, Vredeman de Vries |

| Garden with Arbors, Vredeman de Vries |

Shakespeare Garden, Van Cortlandt House Museum,

Van Cortlandt Park, Colonial Dames of the State

of New York |

| Tudor Manor House with Modern Arrangement of Gardens |

| Garden House in Old English Garden |

| Fountains, Sixteenth Century |

Sunken Gardens, Sunderland Hall, with Unusual

Treatment of Hedges |

| Knots from Markham |

| Simple Garden Beds |

PART ONE

THE GARDEN OF DELIGHT

EVOLUTION OF THE SHAKESPEARE

GARDEN

I

The Medieval Pleasance

SHAKESPEARE was familiar with two kinds of gardens: the stately and magnificent garden that embellished the castles and manor-houses of the nobility and gentry; and the small and simple garden such as he had himself at Stratford-on-Avon and such as he walked through when he visited Ann Hathaway in her cottage at Shottery.

The latter is the kind that is now associated with Shakespeare's name; and when garden lovers devote a section of their grounds to a "Shakespeare garden" it is the small, enclosed garden, such as Perdita must have had, that they endeavor to reproduce.

The small garden of Shakespeare's day, which we so lovingly call by his name, was a little pleasure gardena garden to stroll in and to sit in. The garden, moreover, had another purpose: it was intended to supply flowers for "nosegays" and herbs for "strewings." The Shakespeare garden was a continuation, or development, of the Medieval "Pleasance," where quiet ladies retired with their embroidery frames to work and dream of their Crusader lovers, husbands, fathers, sons, and brothers lying in the trenches before Acre and Ascalon, or storming the walls of Jerusalem and Jericho; where lovers sat hand in hand listening to the songs of birds and to the still sweeter songs from their own palpitating hearts; where men of affairs frequently repaired for a quiet chat, or refreshment of spirit; and where gay groups of lords and ladies gathered to tell stories, to enjoy the recitation of a wandering trouvre, or to sing to their lutes and viols, while jesters in doublets and hose of bright colors and cap and bells lounged nonchalantly on the grass to mock at all thingseven love!

In the illuminated manuscripts of old romans, such as "Huon of Bordeaux," the "Romaunt of the Rose," "Blonde of Oxford," "Flore et Blancheflore, Amadis de Gaul," etc., there are many charming miniatures to illustrate the word-pictures. From them we learn that the garden was actually within the castle walls and very small. The walls of the garden were broken by turrets and pierced with a little door, usually opposite the chief entrance; the walks were paved with brick or stone, or they were sanded, or graveled; and at the intersection of these walks a graceful fountain usually tossed its spray upon the buds and blossoms. The little beds were laid out formally and were bright with flowers, growing singly and not in masses. Often, too, pots or vases were placed here and there at regular intervals, containing orange, lemon, bay, or cypress trees, their foliage beautifully trimmed in pyramids or globes that rose high above the tall stems. Not infrequently the garden rejoiced in a fruit-tree, or several fruit-trees. Stone or marble seats invitingly awaited visitors.

The note here was charming intimacy. It was a spot where gentleness and sweetness reigned, and where, perforce, every flower enjoyed the air it breathed. It was a Garden of Delight for flowers, birds, and men.

To trace the formal garden to its origin would take us far afield. We should have to go back to the ancient Egyptians, whose symmetrical and magnificent gardens were luxurious in the extreme; to Babylon, whose superb "Hanging Gardens" were among the Seven Wonders of the World; and to the Romans, who are still our teachers in the matter of beautiful gardening. The Roman villas that made Albion beautiful, as the great estates of the nobility and gentry make her beautiful to-day, lacked nothing in the way of ornamental gardens. Doubtless Pliny's garden was repeated again and again in the outposts of the Roman Empire. From these splendid Roman gardens tradition has been handed down.

There never has been a time in the history of England where the cultivation of the garden held pause. There is every reason to believe that the Anglo-Saxons were devoted to flowers. A poem in the "Exeter Book" has the lines:

Of odors sweetest

Such as in summer's tide

Fragrance send forth in places,

Fast in their stations,

Joyously o'er the plains,

Blown plants,

Honey-flowing.

No one could write "blown-plants, honey-flowing" without a deep and sophisticated love of flowers.

Every Anglo-Saxon gentleman had a garth, or garden, for pleasure, and an ort-garth for vegetables. In the garth the best loved flower was the lily, which blossomed beside the rose, sunflower, marigold, gilliflower, violet, periwinkle, honeysuckle, daisy, peony, and bay-tree.

Under the Norman kings, particularly Henry II, when the French and English courts were virtually the same, the citizens of London had gardens, "large, beautiful, and planted with various kinds of trees." Possibly even older scribes wrote accounts of some of these, but the earliest description of an English garden is contained in "De Naturis Rerum" by Alexander Neckan, who lived in the second half of the Twelfth Century. "A garden," he says, "should be adorned on this side with roses, lilies, the marigold,