Contents

Guide

For Oliver Sipple

Nothing astonishes men so much as common sense and plain dealing.

R ALPH W ALDO E MERSON

Contents

T HE CIRCUMSTANCES SURROUNDING Gerald Fords formative years, and the several boyhood names by which he was identified, could hardly be more muddled. Born Leslie King Jr. in July 1913, he was two weeks old when his mother, fearing for both their lives, abandoned her brutish husband. Eventually she and her infant son settled in Grand Rapids, Michigan. There she met and in time married a local businessman named Gerald Ford (Sr.). Throughout his childhood the future president was variously known as Junior King, Junior Ford, plain Junior or its diminutive Junie. I have employed these names as appropriate, while making every effort to avoid confusion with either his blood father or the stepfather he considered his true parent. The reader is both forewarned and reassured that the problem solves itself by the time Junie Ford reaches his fifteenth birthday and is rebranded Gerald R. Ford Junior, the name by which he was known until the 1962 death of his stepfather.

Bob Woodward (to Ford speechwriter Robert Hartmann, seventeen years after publication of Hartmanns tell-all White House memoir): Is there anything that stayed hidden that I should know about?

Hartmann: Ford was hidden.

N O ONE WAS more surprised to find himself invited to a White House stag dinner in the spring of 1975 than Senator George McGovern, the prairie populist crushed by Richard Nixon in the 1972 presidential election. McGoverns fierce opposition to the Vietnam War had made him persona non grata to presidents of both parties. Lyndon Johnson never invited me to dinner, the South Dakota Democrat told Nixons successor. And you can be sure that Richard Nixon didnt.

I know, George, replied Gerald Ford. Thats why I asked you. Policy disagreements notwithstanding, the house belongs to everyone. Now more than ever.

Fords penchant for the unexpected was not always so gracefully executed. On a Sunday morning in September 1974, a disbelieving nation woke to the news that he was pardoning Nixon for any and all offenses relating to the June 1972 Watergate break-in and subsequent cover-up that led to the presidents resignation. Carl Bernstein of the Washington Post spoke for millions when he told his journalistic partner Bob Woodward, The son of a bitch pardoned the son of a bitch. Ford used even harsher language in explaining his action.

Overnight Fords approval rating dropped twenty-two points, a descent unmatched in the history of public opinion polling, and a fair measure of how profoundly he had misread the popular mood. Privately Ford countered that he wasnt forgiving Nixon so much as he was trying to forget him; more precisely, to redirect his energies, and the countrys attention, toward a rapidly deteriorating economy as well as escalating tensions in Asia, Africa and the Middle East. Whatever his motives, Fords methods of deciding the fate of his disgraced predecessor shredded any stitches of trust woven during his first month in office. With the stroke of a pen the nations only unelected president had smudged his claims to legitimacy. He also wrote the opening sentence of his historical obituary.

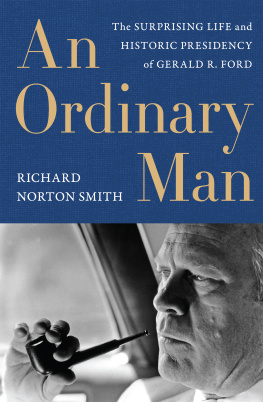

Nearly half a century later, Ford remains the president with an asterisk beside his name. The least self-dramatizing of men, long before No Drama Obama, he guided the nation through its worst constitutional crisis since the Civil War. Later he broke the back of the harshest economic downturn since the Great Depression. And he accomplished both with so little fanfare that he got scant credit for either. To the contrary: in popular memory Ford is wedged between three Shakespearean predecessorsthe idealized JFK, tormented LBJ and self-destructive Nixonand the transformative figure of Ronald Reagan, a sunny revolutionary who remade his party as he replaced the existing New Dealish consensus with one suspicious of, if not hostile to, government solutions.

In such company Ford appears out of his depth, the genial embodiment of a decade recalled more for polyester and platform shoes than as an incubator of meaningful change. It was his misfortune to take the helm in a time of cultural upheaval, during which irony curdled into snark and authority was flogged like a medieval penitent by Saturday Night Live, the satirical game changer that cut its teeth on the new presidents alleged clumsiness and intellectual shortcomings. Admittedly no Great Communicator, Fords verbal gaffes inspired a New York Magazine cover depicting him as Bozo the Clown. A commemorative marker in his hometown of Grand Rapids allegedly read, GERALD FORD SLIPPED HERE .

That Ford should be the last American president capable of conducting his own press briefings on the annual federal budget testifies to an expertise gained during a quarter century as a congressional appropriator. But it was no substitute for Rooseveltian eloquence or Reaganesque wit. This presents a special challenge to the Ford biographer, one neatly summarized in an exchange between the present author and a writer friend whose familiarity with my 2014 life of Nelson Rockefeller evoked a tart parallel. From Rockefeller to Gerald Ford, he mused. Thats the difference between a peacock and a brown sparrow. With the perspective of almost five decades and eight post-Ford presidencies, the subsequent cooling of partisan emotions and access to papers and oral histories formerly off-limits, the time is right for a comprehensive Ford biography that combines scholarly rigor with popular accessibility.

When Jimmy Carter in his 1977 inaugural address complimented his predecessor for all he had done to restore public trust during his brief White House tenure, he fostered an image at once flattering and curiously stilted. In the years since, most Ford portraiture has been of the two-dimensional variety. There is Ford the Healer, saddled with inherited failures (the economy, Vietnam, a runaway CIA) the resolution of which evokes his response when the familys golden retriever soiled the presidential carpet. Waving off some White House stewards, Ford said that no man should have to clean up after another mans dog. Yet that is exactly what he was forced to do, repeatedly, as president. In the shrewd observation of biographer John Robert Greene, Ford the Healer becomes the man who saved the country from Nixon, prepared the country for Carter and Reagan, and did little of substance on his own.

A second, even less complimentary scenario replaces Ford the Healer with Good Old Jerry, congressional warhorseturnedpresidential caretaker, a man whose personal decency could neither compensate for his limited vision nor overcome the stigma of his association with Richard Nixon. Notwithstanding his bold assertion on August 9, 1974, Americas long national nightmare was not over. Far from it. Balancing continuity against change, having no wish to tar innocent staffers with the guilt of their White House superiors, Ford waited too long to expel Nixon holdovers whose allegiance would always be suspect. Nobody leaves the plane without a parachute, he announced. On another occasion he declared, My whole philosophy of life isI dont assume somebody is trying to screw me. Such comments prompted a query rarely heard around 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue: Can a president be too nice to succeed?

Much as Fords public life deserves fresh appraisal, it is his personal story that most calls into question the familiar formulas: An ordinary man summoned by extraordinary events. A politician without guile. What you see iswhat you get. The realityat least the one I have been able to piece togetheris considerably more nuanced. Fords nice guy reputation masked an ambition intense even by modern standards. In 1960 he mounted a vigorous, if futile, campaign to be Richard Nixons running mate. That he learned of Vice President Spiro Agnews legal problems at least six months earlier than he ever acknowledged is revealed here for the first time, as is his cultivation of Democratic support to fill the vacancy left by Agnews resignation in October 1973.