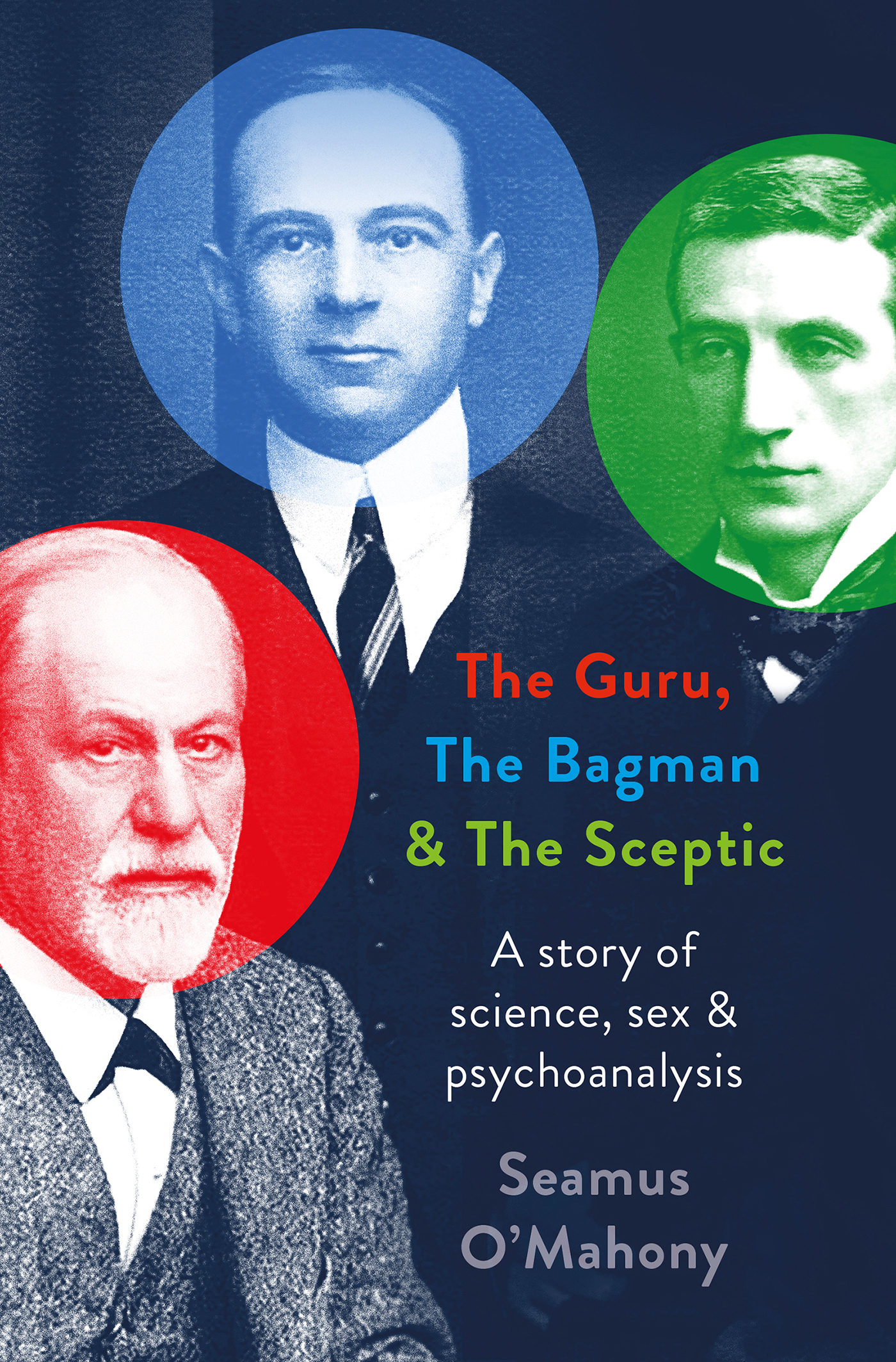

The Guru,

the Bagman

& the Sceptic

The Way We Die Now

Can Medicine Be Cured?

The Ministry of Bodies

The Guru,

the Bagman

& the Sceptic

A story of

Science, sex &

psychoanalysis

Seamus

O'Mahony

www.headofzeus.com

First published in the UK in 2023 by Head of Zeus Ltd,

part of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Copyright Seamus OMahony, 2023

The moral right of Seamus OMahony to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN (HB): 9781803285658

ISBN (XTPB): 9781804548523

ISBN (E): 9781803285634

Head of Zeus Ltd

First Floor East

58 Hardwick Street

London EC 1 R 4 RG

WWW . HEADOFZEUS . COM

To Karen

Whoever undertakes to write a biography binds himself to lying, to concealment, to hypocrisy, to flummery, and even to hiding his own lack of understanding, since biographical truth is not to be had, and even if it were it could not be used.

S IGMUND F REUD , letter to Arnold Zweig, 1936

As to Freud. I think you write greatly about this business but I do not get the sense of illumination, the sense of splendour that you do.

W ILFRED T ROTTER , letter to Ernest Jones, 1908

Contents

This book is about three doctors whose lives intersected over the period from 1908 to 1939. The first, Sigmund Freud, achieved a level of fame that might be called iconic; the second, Ernest Jones, is well known within a single community that of psychoanalysis; the third, the surgeon and author Wilfred Trotter, is all but forgotten, even in the hospital where he was once so revered. If Joness fame is slight, Trotters is even less: it died with the last of his pupils.

Freud remains a cultural figure of the same stature as Karl Marx or Charles Darwin. The twenty-four volumes of his collected writings are afforded a biblical reverence; his every utterance and scribbled letter has been analysed, annotated and interpreted by an academic industry devoted to his thought. Even if his creation psychoanalysis is no longer fashionable (or even slightly disreputable), Freuds status seems unassailable. A century after he achieved global fame, many are puzzled by how Freuds ideas became so widely accepted. It may be as Gibbon wrote of Christianity that it was owing to the convincing evidence of the doctrine itself, but I doubt it. Although I admire Freud, psychoanalysis has always bothered me; I have written this book partly to find out why.

In an aside in his 1916 book Instincts of the Herd in Peace and War , Wilfred Trotter observed: we tend to get at the summit of our professions only those rare geniuses who combine real specialist capacity with the arts of the bagman. Ernest Jones was Freuds bagman. A born disciple, the object of his adoration before Freud was Trotter. Even after Jones transferred his loyalties to Freud and psychoanalysis, he remained connected to Trotter they were, after all, brothers-in-law and their lives crossed at key moments, almost novelistically. If Jones was a disciple and bagman, Trotter was a sceptic and his own man. This is a story of three men, two opposing views of the world, and the fathomless foolishness of humans.

In 1902, Ernest Jones, a twenty-four-year-old house officer at University College Hospital (UCH) London, assisted Wilfred Trotter, a surgical registrar six years his senior, with a double amputation in a man whose legs had been crushed beyond repair. They took a leg each. In his punningly titled memoir Free Associations (1959), Jones takes up the story:

He was what is called a peeper that is, he achieved sexual excitement by witnessing some erotic scene and presumably unable to do so in any other way, the poor fellow used to haunt the Underground Railway (of course in pre-electric times), wait until he observed a likely couple in the separate compartments that made up the trains, and then in the tunnels creep along the footboard to catch the desired glimpse. It was a sprightly occupation, because he had to return to his own compartment before reaching the next station, but doubtless he knew the stretches well from experience and had become skilful at timing it. On the fatal day in question, however, the excitement overcame him; he lost his hold and fell on the line, and a train came along from the opposite direction and cut his legs off. What effect this retaliatory mutilation had on his later mentality I do not know, but one can well imagine it to have been immense; it was a supreme example of a physical and a psychological trauma combined.

With its combination of paraphilia and gristle, Joness story is what we might now lazily label as Freudian, and hints at his future career as psychoanalytic capo .

*

When he was still in his late twenties, and completely unknown, Sigmund Freud told his fiance, Martha, with a Messianic certainty, that he would be the subject of many biographies. In 1944, in a characteristically deferential gesture, Jones abandoned Free Associations to concentrate instead on his biography of Sigmund Freud, published in three volumes, and to great acclaim, between 1953 and 1957. Joness monumental biography may have been a critical and commercial success and may have done much to spread Freuds ideas in the English-speaking world, but nearly all subsequent biographers for, as Freud predicted, there have been several have been at pains to highlight its many errors, both factual and doctrinal. This great hagiographical tribute completed, he took up the memoir again, but died in 1958 at the age of seventy-nine before completing it.

Those who are puzzled by the success of psychoanalysis and the global acceptance of Freuds ideas in the early to mid-twentieth century often blame (or credit) Ernest Jones. The psychiatrist and author Anthony Daniels (who usually writes as Theodore Dalrymple) is a confirmed psychoanalytic sceptic, but even he expressed a grudging admiration for Joness success as a proselytiser, while meditating on his undeserved obscurity:

It is, of course, quite true that Dr. Joness current fame is not equal to his importance. Indeed, I have often thought of conducting the following experiment: to count the number of people it is necessary to accost in the various streets of New York, London, or Sydney before encountering someone who has heard of Ernest Jones. My experiment is a rare opportunity to establish an important law in the field of cultural studies: that in the era of celebrity, fame is inversely related to importance.

Jones saw his relationship to Freud as that of T. H. Huxley to Darwin: we were both bonny fighters. He did all the political, administrative and publishing work that Freud couldnt or didnt want to do. Jones loved this labour: he founded and ran psychoanalytic associations and societies (he was de facto president for life of two); he recruited English translators for Freuds vast written output; he was a one-man intelligence operation, sniffing out heresy and banishing dissenters, feeding information back to Freud in a correspondence lasting thirty years; he almost single-handedly saved Freud after the Anschluss in 1938, when he deployed his extensive diplomatic and political contacts to rescue the sick old man. Jones combined the Huxleyan role with those of Boswell and St Paul.