The Samuel & Althea Stroum Lectures

IN JEWISH STUDIES

The Samuel & Althea Stroum Lectures

IN JEWISH STUDIES

The Yiddish Art Song

performed by Leon Lishner, basso,

and Lazar Weiner, piano

(stereophonic record album)

The Holocaust in Historical Perspective

Yehuda Bauer

Zakhor: Jewish History and Jewish Memory

Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi

Jewish Mysticism and Jewish Ethics

Joseph Dan

The Invention of Hebrew Prose:

Modern Fiction and the Language of Realism

Robert Alter

Recent Archaeological Discoveries and Biblical Research

William G. Dever

Jewish Identity in the Modern World

Michael Meyer

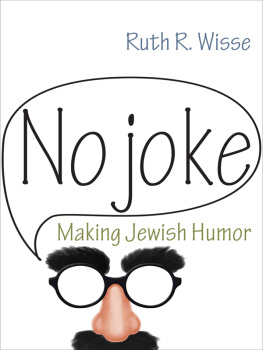

I. L. Peretz and the Making of

Modern Jewish Culture

Ruth R. Wisse

I. L. Peretz

and the

Making

of Modern

Jewish

Culture

RUTH R. WISSE

Copyright 1991 by the University of Washington Press

First paperback edition 2015

All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wisse, Ruth R.

I. L. Peretz and the making of modern Jewish culture / Ruth R. Wisse.

p. cm.(The Samuel and Althea Stroum lectures in Jewish studies)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-295-99479-6 (alk. paper)

1. Peretz, Isaac Leib, 1851 or 2-1915Religion. 2. Peretz, Isaac Leib, 1851 or 2-1915Political and social views. I. Title. II. Title: Making of modern Jewish culture. III. Series.

PJ5129.P4Z97 1991

CIP

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum

requirements of

American National Standard for Information Sciences

Permanence of Paper

for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984

The Samuel & Althea Stroum Lectures

IN JEWISH STUDIES

Samuel Stroum, businessman, community leader, and philanthropist, by a major gift to the Jewish Federation of Greater Seattle, established the Samuel and Althea Stroum Philanthropic Fund.

In recognition of Mr. and Mrs. Stroums deep interest in Jewish history and culture, the Board of Directors of the Jewish Federation of Seattle, in cooperation with the Jewish Studies Program of the Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies at the University of Washington, established an annual lectureship at the University of Washington known as the Samuel and Althea Stroum Lectureship in Jewish Studies. This lectureship makes it possible to bring to the area outstanding scholars and interpreters of Jewish thought, thus promoting a deeper understanding of Jewish history, religion, and culture. Such understanding can lead to an enhanced appreciation of the Jewish contributions to the historical and cultural traditions that have shaped the American nation.

The terms of the gift also provide for the publication from time to time of the lectures or other appropriate materials resulting from or related to the lectures.

To my husband Len Wisse

Acknowledgments

THIS STUDY is based on the series of Stroum lectures I delivered in 1988 at the University of Washington in Seattle. I am very grateful to all those who made the experience so pleasurable, particularly the chairman of the Jewish Studies program Hillel Kieval, its coordinator Dorothy Becker, and Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Stroum, generous benefactors and wonderful hosts. Thanks to the patience and encouragement of Naomi Pascal, editor-in-chief of the University of Washington Press, I managed the transition from lectures to book.

Most of the research for this book was done at the National and Hebrew University Library and Archives in Jerusalem, the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York, Widener Library of Harvard in Cambridge, McGill Universitys MacLennan Library, and the Jewish Public Library of Montreal. I am ever thankful to the staffs of those institutions for the courtesy they continue to show me through the years. I wrote this book at the same time that I was editing volume 2 of the Library of Yiddish Classics, The I. L. Peretz Reader; and many of the works mentioned here can be found in that anthology, enabling readers to set their own impressions against mine.

My brother David Roskies, most generous colleague and friend, was especially helpful in the preparation of this manuscript, though he cannot be held responsible for its flaws. Michael C. Steinlauf shared with me material he had collected from the daily Yiddish press in Poland that would otherwise have remained inaccessible to me. Magda Opalskis friendship and intellectual curiosity make me wish this study of Peretz were more thorough and complete. I am grateful to my erudite colleagues at McGill University, among them some of my closest friends, who have contributed to this work in one way or another. The bibliographical index to Yiddish periodicals prepared under the guidance of Khone Shmeruk and Chava Turniansky of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem was a most welcome, valuable asset. To Khone Shmeruk the field of Yiddish studies owes a special thanks for opening the doors of scholarship and of his home.

In dedicating this book to my husband I am mindful of our good fortune in sharing a culture as well as love. He embodies the ideals of dignity and compassion that we absorbed from Peretz in our youth, along with a sense of humor that makes goodness friendlier.

Introduction

Peretz is the first and finest work of art that the Jewish people created during this brief period of its secular existence.Kiev, April, 1917

... upon the foundations of earlier aesthetic and cultural values Peretz erected a splendid monument that is the quintessence of our spiritual life....Cracow, 1942(?)

The modern secular Jewish world people began to discover itself in the framework of the new world that was coming into being. Its ideology was in place: Yitzkhok Leybush Peretz was its ideology.Tel Aviv, 1972

WITH THE EXCEPTION OF Theodor Herzl, founder of political Zionism, no Jewish writer had a more direct effect on modern Jewry than Isaac Leib (Yitskhok Leybush) Peretz. Peretz may not have promoted any fixed political program, but he tried to chart for his fellow Jews a road that would lead them away from religion toward a secular Jewish existence without falling into the swamp of assimilation. From the mid-1880s until his death at the beginning of World War I, he shaped literature in Yiddish, and to a lesser extent Hebrew, into an expression and instrument of national cohesion that would help to compensate the Jews for the absence of such staples of nationhood as political independence and territorial sovereignty. He expected that the modern culture of the Jews, embodying the distilled ethics of centuries of religious refinement, would help to sustain the modern people much as Biblical and Talmudic literature and learning had sustained Jews in the past. More by intuition than considered plan, Peretz groped his way toward a politics of culture.