Pandls brunch. From left to right: George, Jeremiah, Amy, Johnny, Chrissy, Peggy, Stevie, Katie, Jimmy, and Julie.

Memoir of the Sunday Brunch

Julia Pandl

ALGONQUIN BOOKS OF CHAPEL HILL 2013

To my parents, George and Terry, for showing me the way.

And to my siblings, Johnny, Jimmy, Katie, Peggy, Chrissy, Amy, Stevie, and Jeremiah, for showing me a whole bunch of other stuff.

And to everyone whose first job was at George Pandls in Bayside.

George and Terry leaving their wedding.

The family. In back, left to right: Jimmy, Johnny, Jeremiah, Katie, Julie; in front, left to right: Stevie, Amy, Peggy, Chrissy.

Contents

Authors Note

Th ese are my stories as I remember themthe ones that have survived the march of time and left their mark. Granted, my memory is not what it used to be, but I tried to be as true to the events as possible. One or two names have been omitted or changed to protect the innocent, the guilty, and the disgusting.

Terry.

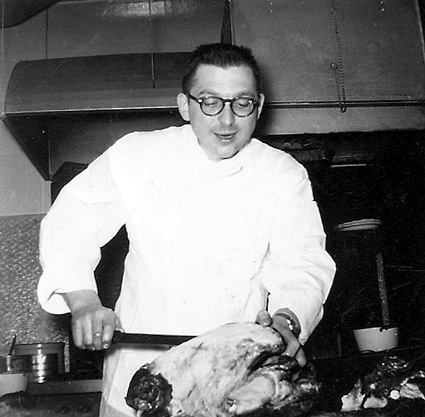

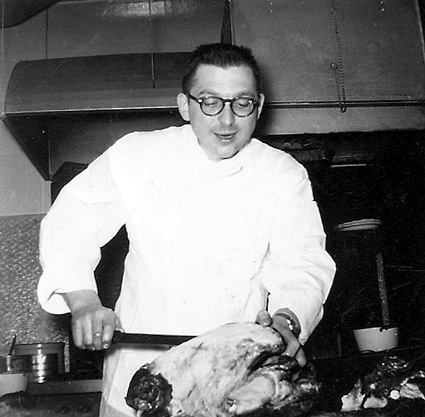

George.

PART I

All the worlds a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances;

And one man in his time plays many parts...

William Shakespeare, As You Like It

Blueberry or Plain

I thought my dad was just like every other dad, until the day I worked my first Sunday brunch. I stepped over a line that afternoon, a thin wrinkle in time, hanging in the ether between breakfast and lunch. It was subtle, a wisp of a moment, like God giggling as he licked his thumb and turned the page on Providence. Distracted by the fact that my father had traded his sanity for a paper chef hat and a set of utility tongs, I missed itbut the moment happened. Th ey say the Lord rested on the seventh day. Not so. He went out to brunch with the rest of creation.

I began working at my fathers restaurant, with the rest of my siblings, at twelve. George, my father, enlisted all of us at an early age. Child labor laws didnt apply back then in our family, so my father could do anything he wanted with us, and he did. Th ere were nine of us: Johnny, Jimmy, Katie, Peggy, Chrissy, Amy, Steve, Jeremiah, and me. I never thought there was anything unusually large about my family. I still dont. Today, when people hear nine kids, they always gasp. Th e gasp that offers an implied a lot or too many or holy cow. But when youre number nine, when youre the last one who arrives at the party, just before time runs out and the uterine door is slammed shut forever, you dont gaspyou sigh. I suppose some of the older siblings, the ones forced to rinse out poopy diapers left soaking in the toilet before they used it, may have occasionally thought eight or nine was one or two too many, but not me. I never saw what life looked like without them. Sure, I imagined it, every time Jeremiah stuck his disgusting bulbous white wart in my face, but that just doesnt count. To me, nine was normal.

I never saw what life looked like before the restaurant either. It was present in the definition of our familythe member that equaled the whole. Employment there, when we were kids, was simply understood. Every day the sun came up, and food needed to be prepared. I never heard a single conversation regarding whether or not one my siblings would go to work. What I did hear was the phone ringing, someone calling in sick, and Peggy and Chrissy fighting about whose turn it was to go. Perhaps we could have unionized, but we were too scared, and too small, to think of such a thing. Th e eight of them went before me, some before their tenth birthday, so I guess I was lucky.

Heres how I ended up in my fathers chain gang: I slipped up and got caught stealing time on the sofa.

It was July, I think, 1982. Our summer cottage in Cedar Grove had become our permanent residence the previous August. It was a Swiss chalet replica tucked at the end of a gravel road along the Wisconsin shore of Lake Michigan. I had access to some of the most pristine beach in North America, yet instead I chose to watch TV. Late one beautiful Saturday morning, George, my father, caught me lying on our woolly plaid couch, still in my Lanz nightgown, watching Th e Lone Ranger . Th at was the moment I kissed unemployment good-bye.

Admittedly, it was a rookie mistake. Even at twelve, I knew enough to run from the TV when I heard his footsteps on the loose floorboard outside their bedroom door. Television existed in our house for the moon landing, assassinations, and my mothers sanity. Period. For us kids, any enjoyment via TV was strictly prohibited.

So that morning, my father went on a semi-hysterical tirade about a beautiful summer day, reading a book, laziness, and the covered-wagon days.

I just sat there with my mouth open.

Th en, his parting words, Youre coming with me to work the brunch tomorrow, slapped me out of the televisions tranquil grip.

Maybe I sabotaged myself, because in truth, I was actually excited to go. I adored my siblings, and aside from Jeremiah, they had been trickling out the door, one by one, for years. Johnny and Jimmy were married with families of their own, and the rest were either in college or getting ready to start. When they did come home on weekends and holidays, usually to work, I felt an excitement that I think is unique to the babies of the familyand puppies. If Id had a tail, it would have wagged. So I raced to catch up with them; anything they were allowed to do that I wasnt held a delicious mystique. Once in a while, as our parents slept, my siblings secretly let me sit on a lap at the kitchen table in my pajamas, teaching me how to fold pizza and say shit while they chatted with their friends. But their time at the restaurant had still remained a mystery. After a full day at work, they came home with hands smelling of smoked fish and stale strawberries. I heard tales of needle-nose pliers and slipping the pinbones from a side of whitefish. Th ey never talked much about George. Looking back, it seems a little odd. I honestly dont think it ever occurred to any of them to alert me, to say something like, Hey, heads up, Dads... um... not quite right on Sundays, so dont do anything stupid. Th at would have been nice, but its not how they rolled. In a family business, some things, no matter how out of the ordinary, are just accepted as normal. Th ey didnt know any better; therefore, neither did I. All I knew was that when my time finally came, I would clean flat after flat of strawberries. And I would do it as well and as quickly as my siblings did, if not better and faster.

OF COURSE, I had been at the restaurant hundreds of times. More often than not, though, I was just along for the ride. I had never worked an entire day. Sometimes I carried a five-gallon pickle bucket and cleaned the parking lot of candy wrappers and chewed gum, but mostly I just sat at the bar, ate hot fudge sundaes, and waited for someone to take me home. My sister Katie would make fluffy grasshoppers for the customers, then pour me the remains from the blender. It was wickedly cool, minty, and grown up.