My deepest gratitude to my friends and familysome of whom have helped me directly through suggestions and comments, and all of whom have sustained me with their consistent and loving support. This book wouldn't have happened without you.

Thanks, too, to my wonderful agent and friend, Martha Millard, and to Daniel Menaker at Random HouseI couldn't have asked for a more enthusiastic, perceptive, and caring editor.

ONE

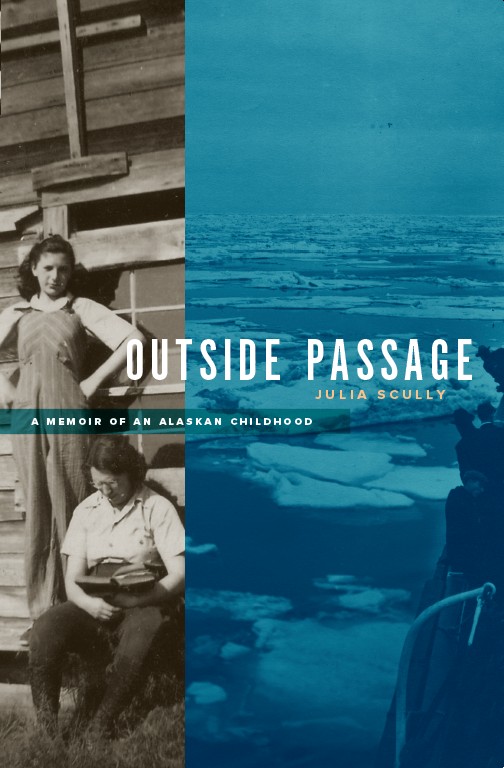

There wasn't a single tree in Nome. There wasn't a road that connected it to any other village or town. It would take you ten days to get there from Seattle on the Outside Passagea rough voyage on the open sea with one landfall at the tip of the Aleutian Islands.

You could walk the entire town in five minutes. Well, maybe ten. Except for the Sand Spit. But there was nothing on that narrow stretch of sand beyond the jetty anyway, nothing but a few Eskimo hovels. About half of Nome's population of some 1,800 was Eskimo, or part-Eskimocalled half-breeds or quarter-breeds. By and large, the whites looked on the natives as backward children.

If you walked to the northern edge of town, you came to the tundraa brown, treeless, barren expanse. If you reversed yourself and went as far as you could in the opposite direction, you found Front Street and, just beyond it, the Bering Sea. Siberia was 200 miles away.

Except for Front Street, none of the streets in Nome had names. Or, if they did, no one knew them. There was one paved sidewalk, the one around the Federal Building, the three-winged, concrete centerpiece of Front Street that housed the post office, the court, the jail, and the land office where you went to stake a claim. The other sidewalks, when they existed, were wooden planks. The streets were mud in the summer, hard-packed snow in the winter.

The houses and the stores were little more than shacks clinging to the edge of the Bering Sea. Every fall there'd be a big storm, with the waves sometimes breaking over the buildings along Front Street, washing them out to sea or smashing them so that they lay on the ground like so many discarded toothpicks. Soon after, the ice pack drifted in from the Arctic, closing off the Bering Sea, and then it was silent, still, and white as far as the horizon and beyond. There followed seven long months of winter with the wind howling off the tundra, sweeping across the treeless outpost, whipping the snow into drifts that sometimes covered the houses, so that you had to shovel your way out.

The clear days were worse than the stormy ones. The ice crystals hung in the frigid air, stinging your chin, your cheeks, your nose, leaving them numb. You tried to keep your mouth closed, to shut out the freezing air. On such days there was hardly a soul on Front Street, although the Eskimos stood around sometimes in their parkas and mukluks, not seeming to notice that it was twenty below zero.

If you made the mistake of dying during the winter, you had to wait until spring to get buried.

The town had no sewer, no sanitation department. Unless you counted Eli the Scavenger. Eli poured the contents of the euphemistically named chemical toilets into an open, horse-drawn wagon. The stench of that wagon hung in the air and clung to your clothes after he passed. When he made his twice-weekly collections at your house, his own stink lingered for hours.

By spring, the snowdrifts, sometimes higher than a man's head, were black with soot from the oil smoke and dotted with dog droppings from the malamutes who roamed the streets in packs. Only a few people kept teams anymore, so there was no use for the animals.

Everyone in Nome looked forward to the breakup in the spring, when the ice would drift back to sea. It seemed to happen overnight. You looked out the window one morning and, instead of the momentously still white landscape, you'd see only small pieces of drifting ice now helplessly tossed and pounded by the turbulent water. Then everyone waited and watched every day, stopping on their errands to peer between the buildings on Front Street toward the horizon, looking for the First Boat to pull into the roadstead.

The First Boat that would bring clothes and furniture from Sears, Roebuck and Montgomery Ward, machinery for the gold-mining camps, a few precious cartons of fresh fruit and vegetables after months of nothing but canned, supplies for the stores on Front Street. And passengersmen arriving for seasonal work at the gold-mining camps, women and children returning from a winter Outside in Seattle, or in Bellingham or Walla Walla, rejoining fathers and husbands whose work had required them to stay on, stay on through the long, brutal winter. And a few Cheechakosthe Alaskan's term for newcomers.

In the spring of 1940 my sister, Lillian, who was thirteen, and I, who was eleven, arrived alone on the First Boat to Nome.

TWO

Our journey to Nome began, you might say, on a day four years earlier in San Francisco. It was a brilliant October afternoon, glistening with the dazzling light peculiar to that citya light that etched the edges of the shabby white apartment houses, creating sharp white lines against the cloudless blue sky, and caused the mica in the sidewalk to flash in our eyes as my sister and I made our way up Sutter Street on our way home from school.

We crossed wide Van Ness Avenue, a boulevard of automobile showrooms beyond which Sutter took a sharp rise. We might have stopped in the little bakery, where we sometimes bought a chocolate clair to split between us. I can remember the way the warm chocolate icing melted into the whipped cream in my mouth. But perhaps we didn't have the dime that day and continued up Sutter past Butterfield & Butterfield, the auction house, where a fragile chair sat in the window like an actor on a stage, framed by an arch of velvet curtains. On past the small, three-story apartment houses such as the one in which we lived, round the corner to the dark shadows of Franklin Street, where our mom and dad had a coffee shop.