William L. Iggiagruk Hensley - Fifty Miles from Tomorrow: A Memoir of Alaska and the Real People

Here you can read online William L. Iggiagruk Hensley - Fifty Miles from Tomorrow: A Memoir of Alaska and the Real People full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2010, publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Fifty Miles from Tomorrow: A Memoir of Alaska and the Real People

- Author:

- Publisher:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Genre:

- Year:2010

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

Fifty Miles from Tomorrow: A Memoir of Alaska and the Real People: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Fifty Miles from Tomorrow: A Memoir of Alaska and the Real People" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Nunavut tigummiun!

Hold on to the land!

It was just fifty years ago that the territory of Alaska officially became the state of Alaska. But no matter who has staked their claim to the land, it has always had a way of enveloping souls in its vast, icy embrace.

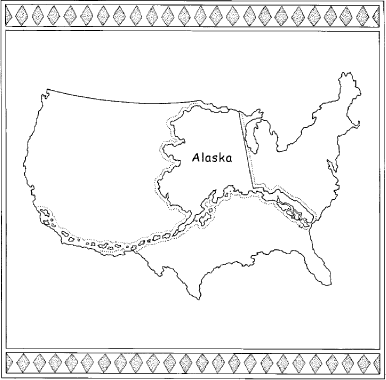

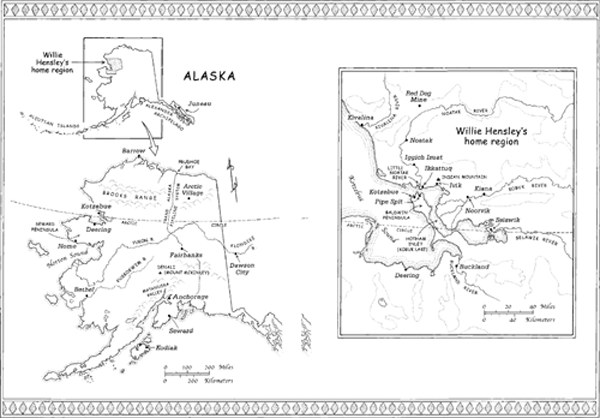

For William L. Iggiagruk Hensley, Alaska has been his home, his identity, and his cause. Born on the shores of Kotzebue Sound, twenty-nine miles north of the Arctic Circle, he was raised to live the traditional, seminomadic life that his Iupiaq ancestors had lived for thousands of years. It was a life of cold and of constant effort, but Hensleys people also reaped the bounty that nature provided.

In Fifty Miles from Tomorrow, Hensley offers us the rare chance to immerse ourselves in a firsthand account of growing up Native Alaskan. There have been books written about Alaska, but theyve been written by Outsiders, settlers. Hensleys memoir of life on the tundra offers an entirely new perspective, and his stories are captivating, as is his account of his devotion to the Alaska Native land claims movement.

As a young man, Hensley was sent by missionaries to the Lower Forty-eight so he could pursue an education. While studying there, he discovered that the land Native Alaskans had occupied and, to all intents and purposes, owned for millennia was being snatched away from them. Hensley decided to fight back.

In 1971, after years of Hensleys tireless lobbying, the United States government set aside 44 million acres and nearly $1 billion for use by Alaskas native peoples. Unlike their relatives to the south, the Alaskan peoples would be able to take charge of their economic and political destiny.

The landmark decision did not come overnight and was certainly not the making of any one person. But it was Hensley who gave voice to the cause and made it real. Fifty Miles from Tomorrow is not only the memoir of one man; it is also a fascinating testament to the resilience of the Alaskan ilitqusiat, the Alaskan spirit.

William L. Iggiagruk Hensley: author's other books

Who wrote Fifty Miles from Tomorrow: A Memoir of Alaska and the Real People? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

N ew Y ork

N ew Y ork

, , m, n, , , p, q, r, s, sr, t, u, v, y. Many of these letters represent the same sound as their English equivalents.

, , m, n, , , p, q, r, s, sr, t, u, v, y. Many of these letters represent the same sound as their English equivalents.