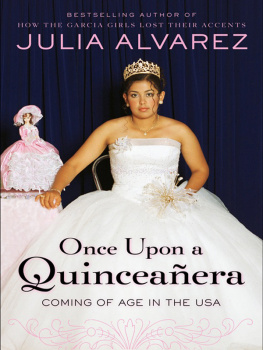

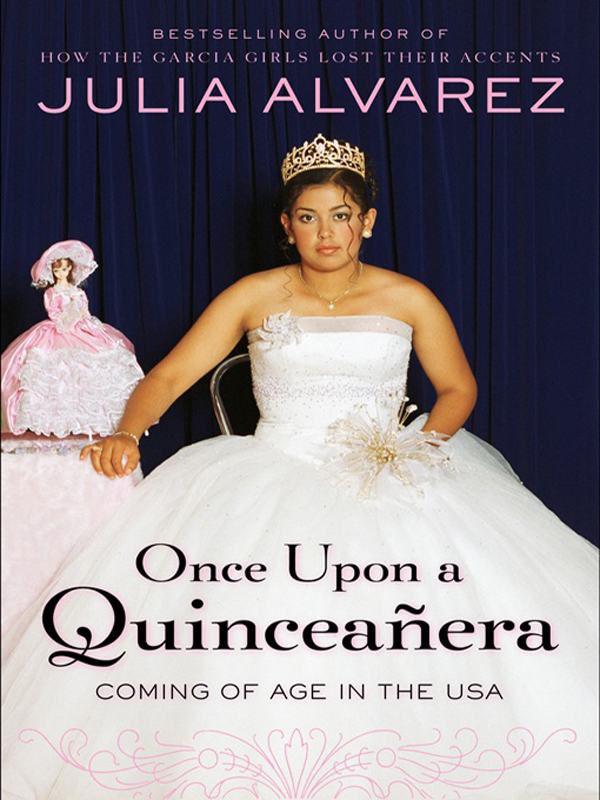

Once Upon a Quinceaera

COMING OF AGE IN THE USA

Julia Alvarez

Viking

VIKING

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi110 017, India Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0745, Auckland, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd.) Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

first published in 2007 by Viking Penguin, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Copyright Julia Alvarez, 2007

All rights reserved

Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint the following copyrighted works: Excerpt from The Worlds Gone Crazy by Jeff Durand and Tommy Barbarella. Used with permission. Excerpt from Querida Companera from Loving in the War Years by Cherrie Morega (South End Press). Copyright 1983 by Cherrie Morega. Used by permission of the author. Excerpts from for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf by Ntozake Shange. Copyright 1975, 1976, 1977 by Ntozake Shange. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission of Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Adult Publishing Group. Father and Child (from A Woman Young and Old) from The Collected Works of W. B. Yeats, Volume I: The Poems (revised), edited by Richard J. finneran. Copyright 1933 by The Macmillan Company; copyright renewed 1961 by Bertha Georgie Yeats. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission of Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Adult Publishing Group.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA

Alvarez, Julia.

Once upon a quinceaera / Julia Alvarez.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN: 978-1-1012-1340-7

1. Quinceaera (Social custom)United States. 2. Hispanic AmericansSocial life and customs. 3. Hispanic AmericansRites and ceremonies. I. Title.

GT249C.A45 2007395.2'4dc22 2006037561

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrightable materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated.

btb_ppg_c0_r1

for

all the girls

and for

the wise women

who raise them

Education is teaching our children to desire the right things.

Plato

Contents

Invitation

Y OU ARE DRESSED in a long, pale pink gown, not sleek and diva-ish, but princessy, with a puffy skirt of tulle and lace that makes you look like youre floating on air when you appear at the top of the stairs. Your court of fourteen couples has preceded you, and now they line up on the dance floor, forming a walkway through which you will pass to sit on a swing with garlanded ropes, cradling your last doll in your arms. Your mami will crown you with a tiara recessed in a cascade of curls the hairstylist spent most of the afternoon sculpting on your head. Then your papi will replace the flats you are wearing with a pair of silver heels and lead you out to the dance floor, where you will dance a waltz together.

No, you are not Miss America or a princess or an actress playing Cinderella in a Disney movie. In fact, you are not exceptionally beautiful or svelte and tall, model material. Your name is Mara or Xiomara or Maritza or Chantal, and your grandparents came from Mexico or Nicaragua or Cuba or the Dominican Republic. Your family is probably not rich; in fact, your mami and papi have been saving since you were a little mortgaged the house or lined up forty godparents to help sponsor this celebration, as big as a wedding. If challenged about spending upward of five thousand dollarsthe average budgeton a one-night celebration instead of investing in your college education or putting aside the money for their own mortgage payments, your parents will shake their heads knowingly because you do not understand: this happens only once.

What is going on?

You are having your quinceaera, or fiesta de quinceaos, or, simply, your quince. And one day when you are as old as your grandmother and you want to say to some young person, hey, I once was young, too, the expression you will use is Yo tambin tuve mis quinces.

I, too, had my quinces.

You will want to claim that magic age in which a Latina girl ritually becomes a woman in a ceremony known as a quinceaera.

What exactly is a quinceaera?

The question might soon be rhetorical in our quickly Latinoizing American culture. Already, there is a quinceaera Barbie; quinceaera packages at Disney World and Las Vegas; an award-winning movie, quinceaera; and for tots, Dora the Explorer has an episode about her cousin Daisys quinceaera.

A quinceaera (the term is used interchangeably for the girl and her party) celebrates a girls passage into womanhood with an elaborate, ritualized fiesta on her fifteenth birthday. (Quince aos, thus quinceaera, pronounced: keen-seah-gneer-ah. ) In the old countries, this was a marker birthday: after she turned fifteen, a girl could attend adult parties; she was allowed to tweeze her eyebrows, use makeup, shave her legs, wear jewelry and heels. In short, she was ready for marriage. (Legal age for marriage in many Caribbean and Latin and Central American countries is, or until recently was, fifteen or younger for females, sixteen or older for males.) Even humble families marked a girls fifteenth birthday as special, perhaps with a cake, certainly with a gathering of family and friends at which the quinceaera could now socialize and dance with young men. Upper-class families, of course, threw more elaborate parties at which girls dressed up in long, formal gowns and danced waltzes with their fathers.

Somewhere along the way these fancier parties became highly ritualized. In one or another of our Latin American countries, the quinceaera was crowned with a tiara; her flat shoes were changed by her father to heels; she was accompanied by a court of fourteen damas escorted by fourteen chambelanes, who represented her first fourteen years; she received a last doll, marking both the end of childhood and her symbolic readiness to bear her own child. And because our countries were at least nominally Catholic, the actual party was often preceded by a Mass or a blessing in church or, at the very least, a priest was invited to give spiritual heft to the fiesta. These celebrations were covered in the newspapers, lavish spreads of photos I remember poring over as a little girl in the Dominican Republic, reassured by this proof that the desire to be a princess did not have to be shed at the beginning of adulthood, but could in fact be played out happily to the tune of hundreds upon thousands of Papis pesos.