THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2013 by Karen Russell

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Selected stories in this work were previously published in the following: Vampires in the Lemon Grove in Zoetrope: All Story (2007) and subsequently in The Best American Short Stories (2008) and Making Literature Matter, 5th Edition (2011); The Barn at the End of Our Term in Granta (Spring 2007); The Seagull Army Descends on Strong Beach in Tin House (Fall 2009) and subsequently in The Best American Short Stories (2010); Dougbert Shackletons Rules for Antarctic Tailgating in Tin House (Spring 2010); The Graveless Doll of Eric Mutis in Conjunctions (Fall 2010); Proving Up was published as The Hox River Window in Zeotrope: All Story (Fall 2011); Reeling for the Empire in Tin House (Winter 2012); and The New Veterans in Granta (Winter 2013).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Russell, Karen, [date]

Vampires in the lemon grove : stories / by Karen Russell. 1st ed.

p. cm.

This is a Borzoi book.

eISBN: 978-0-307-96108-2

I. Title.

PS 3618. U V 36 2013

813.6dc23

2012027415

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the authors imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

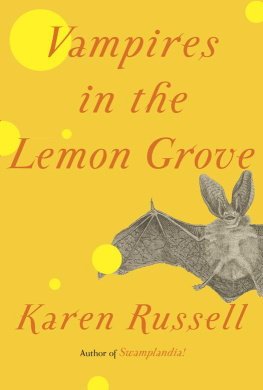

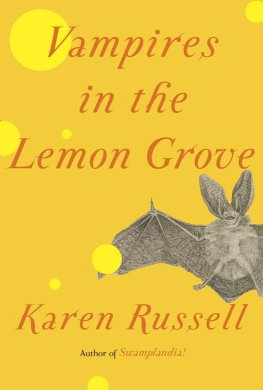

Jacket illustration: Long-Eared Bat , engraving by Heath, print by G. Kearsley, courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Jacket design by Carol Devine Carson

v3.1_r1

For J.T .

CONTENTS

Vampires in the Lemon Grove

In October, the men and women of Sorrento harvest the primofiore , or first flowering fruit, the most succulent lemons; in March, the yellow bianchetti ripen, followed in June by the green verdelli . In every season you can find me sitting at my bench, watching them fall. Only one or two lemons tumble from the branches each hour, but Ive been sitting here so long their falls seem contiguous, close as raindrops. My wife has no patience for this sort of meditation. Jesus Christ, Clyde, she says. You need a hobby.

Most people mistake me for a small, kindly Italian grandfather, a nonno . I have an old nonno s coloring, the dark walnut stain peculiar to southern Italians, a tan that wont fade until I die (which I never will). I wear a neat periwinkle shirt, a canvas sunhat, black suspenders that sag at my chest. My loafers are battered but always polished. The few visitors to the lemon grove who notice me smile blankly into my raisin face and catch the whiff of some sort of tragedy; they whisper that I am a widower, or an old man who has survived his children. They never guess that I am a vampire.

Santa Francescas Lemon Grove, where I spend my days and nights, was part of a Jesuit convent in the 1800s. Today its privately owned by the Alberti family, the prices are excessive, and the locals know to buy their lemons elsewhere. In summers a teenage girl named Fila mans a wooden stall at the back of the grove. Shes painfully thin, with heavy black bangs. I can tell by the careful way she saves the best lemons for me, slyly kicking them under my bench, that she knows I am a monster. Sometimes shell smile vacantly in my direction, but she never gives me any trouble. And because of her benevolent indifference to me, I feel a swell of love for the girl.

Fila makes the lemonade and monitors the hot dog machine, watching the meat rotate on wire spigots. Im fascinated by this machine. The Italian name for it translates as carousel of beef. Who would have guessed at such a device two hundred years ago? Back then we were all preoccupied with visions of apocalypse; Santa Francesca, the foundress of this very grove, gouged out her eyes while dictating premonitions of fire. What a shame, I often think, that she foresaw only the end times, never hot dogs.

A sign posted just outside the grove reads:

CIGERETTE PIE

HEAT DOGS

GRANITE DRINKS

Santa Francescas Limonata

THE MOST REFRISHING DRANK ON THE PLENET!!

Every day, tourists from Wales and Germany and America are ferried over from cruise ships to the base of these cliffs. They ride the funicular up here to visit the grove, to eat heat dogs with speckly brown mustard and sip lemon ices. They snap photographs of the Alberti brothers, Benny and Luciano, teenage twins who cling to the trees wooden supports and make a grudging show of harvesting lemons, who spear each other with trowels and refer to the tourist women as vaginas in Italian slang. Buona sera , vaginas! they cry from the trees. I think the tourists are getting stupider. None of them speak Italian anymore, and these new women seem deaf to aggression. Often I fantasize about flashing my fangs at the brothers, just to keep them in line.

As I said, the tourists usually ignore me; perhaps its the dominoes. A few years back, I bought a battered red set from Benny, a prop piece, and this makes me invisible, sufficiently banal to be hidden in plain sight. I have no real interest in the game; I mostly stack the pieces into little houses and corrals.

At sunset, the tourists all around begin to shout. Look! Up there! Its time for the path of I Pipistrelli Impazziti the descent of the bats.

They flow from cliffs that glow like pale chalk, expelled from caves in the seeming billions. Their drop is steep and vertical, a black hail. Sometimes a change in weather sucks a bat beyond the lemon trees and into the turquoise sea. Its three hundred feet to the lemon grove, six hundred feet to the churning foam of the Tyrrhenian. At the precipice, they soar upward and crash around the green tops of the trees.

Oh! the tourists shriek, delighted, ducking their heads.

Up close, the bats spread wings are alien membranesfragile, like something internal flipped out. The waning sun washes their bodies a dusky red. They have wrinkled black faces, these bats, tiny, like gargoyles or angry grandfathers. They have teeth like mine.

Tonight, one of the tourists, a Texan lady with a big strawberry red updo, has successfully captured a bat in her hair, simultaneously crying real tears and howling: TAKE THE GODDAMN PICTURE, Sarah!

I stare ahead at a fixed point above the trees and light a cigarette. My bent spine goes rigid. Mortal terror always trips some old wire that leaves me sad and irritable. It will be whole minutes now before everybody stops screaming.

THE MOON IS a muted shade of orange. Twin disks of light burn in the sky and the sea. I scan the darker indents in the skyline, the cloudless spots that I know to be caves. I check my watch again. Its eight oclock, and all the bats have disappeared into the interior branches. Where is Magreb? My fangs are throbbing, but I wont start without her.

I once pictured time as a black magnifying glass and myself as a microscopic flightless insect trapped in that circle of night. But then Magreb came along, and eternity ceased to frighten me. Suddenly each moment followed its antecedent in a neat chain, moments we filled with each other.

I watch a single bat falling from the cliffs, dropping like a stone: headfirst, motionless, dizzying to witness.

Pull up .

I close my eyes. I press my palms flat against the picnic table and tense the muscles of my neck.

Next page