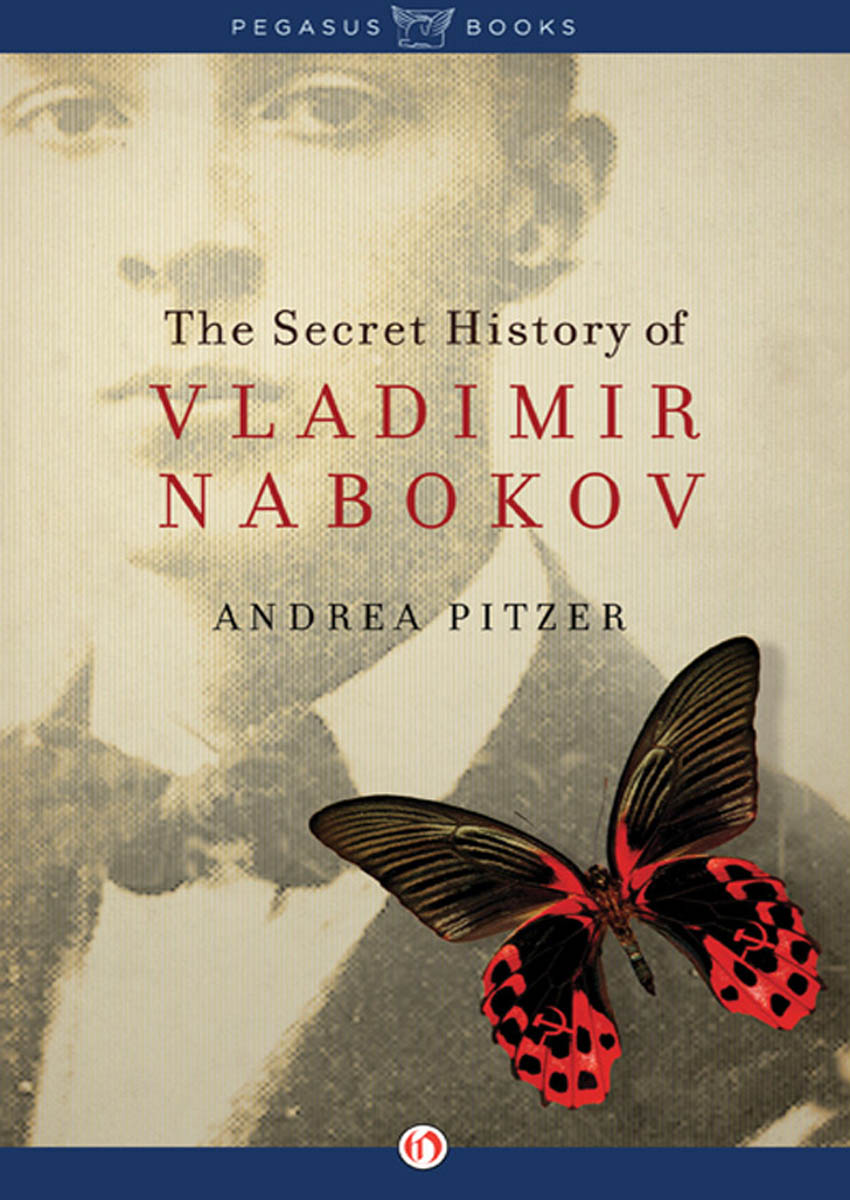

The Secret History of

VLADIMIR

NABOKOV

ANDREA PITZER

PEGASUS BOOKS

NEW YORK LONDON

To the dead and the dreams

of a lost century

C HAPTER O NE

Waiting for Solzhenitsyn

On October 6, 1974, Russian novelist Vladimir Nabokov and his wife Vra sat in a private dining room of the Montreux Palace Hotel in Switzerland, waiting for Alexander Solzhenitsyn to join them for lunch. The two men had never met.

By then the Nabokovs had been living in the opulent Palace Hotel, tucked along the eastern shore of Lake Geneva, for thirteen years. During those years, literary pilgrims had traveled to Montreux in hopes of an audience with the master. When they were lucky enough to meet with him, Nabokov had fielded their questions and returned biting, playful answers. They had sipped coffee, tea, or grappa at lunchtime with one of the most celebrated wordsmiths in the world, and plumbed his cryptic statements for meaning. Pursuing him as he pursued butterflies, they had climbed the Alpine slopes that vaulted up behind the hotel.

The seventy-five-year-old Nabokov saw himself as Russian and American, yet lived in rented rooms in neither country, continuing to work on new books and translations at an exhausting pace that Lolitas breakthrough more than a decade before had rendered financially unnecessary. He had grown accustomed to being courted, and to delighting his guests. But a visit from Solzhenitsyn was something different.

The morning of October 6 revealed itself early on as a rainy day, but in truth, the weather on the drive south from Zurich may not have mattered to Solzhenitsyn. Only eight months earlier, Solzhenitsyn had been sitting in a cell at Moscows Lefortovo Prison, charged with treason against the Soviet Union. The deportation that followed his arrest had been bitter, but there were, he knew, more permanent penalties than exile.

Solzhenitsyn had dreamed of face-to-face confrontation with Soviet leaders, believing that pressure at the right moment by the right person might topple the whole system of repression, or at least begin its destruction. Instead, expulsion had delivered him into Frankfurt, Germany, and an uncharted life. And so he was not in prison, not shouting his defiance to the Politburo or meeting privately with Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev. After a spring and summer spent making his way in the new world, he instead found himself cruising the Swiss countryside with his wife Natalia, circling Lake Geneva, traveling Montreuxs elegant Grand Rue on his way to see one of the most celebrated authors in the worlda man he himself had nominated for the Nobel Prize just two years earlier. Yet Solzhenitsyn was nervous.

At that moment, it would have been hard to find two bigger literary superstars than the man who had written The Gulag Archipelago and the author of Lolita. They were both Russian, but the nineteen years between their births had destined them to grow up in separate universes. Nabokov had come of age in the last days of the Tsar and Empire, ceding Russia to the Bolsheviks, sailing away under machine-gun fire before the infant Solzhenitsyn had learned to walk. Solzhenitsyn had grown up in the Soviet state, spending years inside its concentration camps and prisons before emerging from behind the Iron Curtain on a mission to reveal a reign of terror and end it forever.

Physically, the men were as dissimilar as their histories. With Nabokov, molasses candy and modern dentures had created a plump, mild professor from a gaunt migr, while Solzhenitsyns scarred forehead, wild hair, and prophets beard marked him as a more volatile presence. Their writing voices, too, stood distinct one from the other, Nabokovs exquisite language and baroque experiments contrasting with Solzhenitsyns open fury and direct appeals to emotion.

Even their most famous books seem opposite in nature. The Gulag Archipelago chronicles the entire history of the Soviet concentration camp system, bluntly cataloguing the abuse of power on an epic scale, while Nabokovs Lolita maps a more individual horror: the willful savaging of one human being by another. A microscopically detailed account of a middle-aged mans sexual obsession with a young girl, Lolita has been variously described as funny, the only convincing love story of our century, and the filthiest book I have ever read. Humbert Humberts tale of the two-year molestation of his stepdaughter describes their relationship, her escape with another man, and Humberts revenge on his romantic rival in merciless, vivid language. The narrators frankness about his desire for and relations with a child destined the book to pass through scandal on its way to immortality.

Lolita had started her long reign over the American bestseller lists in 1958, by which point Nabokov had been garnering critical attention on both sides of the Atlantic for decades. But it was his nymphet noveland the risqu film Stanley Kubrick made from itthat launched him into notoriety, then celebrity. Banned in Australia, Buenos Aires, and at the Cincinnati Public Library, Nabokovs novel had managed to sell more copies in its first three weeks in America than any book since Gone with the Wind.

And just as Solzhenitsyn mapped a uniquely Soviet geography in The Gulag Archipelago, Nabokov laid out the landscape of postwar America in Lolita. It was an entirely different archipelagoone of roadside motels, sanatoriums, hotel conferences, pop psychology, immigrant drifters, a Kansas barber, a one-armed veteran, Safe-ways and drugstores, sanctimonious book clubs, and an unnerving religiosity. It was a glorious, expansive, intolerant, and amnesiac backdrop, one that revealed just as much as Solzhenitsyns opus about the country in which it was set, a stage perfectly suited for a story of betrayal and corruption.

After Lolitas phenomenal launch, Nabokov had sold the film and paperback rights for six figures each. Traveling to Hollywood, he rubbed shoulders with John Wayne, whom he did not recognize, and Marilyn Monroe, whom he did. He left his career as an American college professor, becoming the subject of New Yorker cartoons and late-night television comedy. On overseas trips, he was accosted by the press and written up in a half-dozen languages across the continent.

His morals were called into question (utterly corrupt, raged one New York Times critic), but over time his detractors tended to be mocked as puritans and killjoys. The sexually swinging era that followed Lolitas creation was not of Nabokovs making, but its mores helped influence the perception of the book in subsequent years. By the time Solzhenitsyn arrived in Germany, Lolita had become part of a stable of stories about older men with an itch for underage, promiscuous partners. Websters, Nabokovs favorite dictionary, would eventually add Lolitas name to its pages, offering up the off-kilter definition of a precociously seductive girl.

The books linguistic richness and power vaulted it into an existence in which it took on meanings independent of its creator. In vain would Nabokov describe how his nymphet was one of the most innocent and pure among the gallery of slaves he had created as characters; to no avail would Vra remind reporters of how a captive