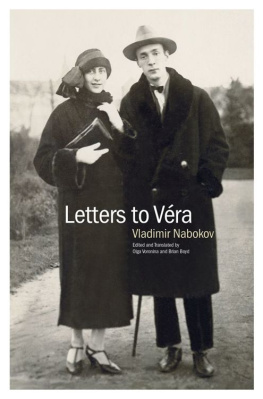

Vladimir Nabokov was born in St Petersburg in 1899, the elder son of an aristocratic, cultured, politically liberal family. When the Bolsheviks seized power the family left Russia and moved first to London, then to Berlin, where Nabokov rejoined them in 1922, after having completed his studies at Trinity College, Cambridge. Between 1923 and 1940 he published novels, short stories, plays, poems and translations in the Russian language and was recognized as one of the outstanding writers of the emigration. In 1940 he and his wife and son moved to America, where he was a lecturer at Wellesley College from 1941 to 1948. He was then Professor of Russian Literature at Cornell University until he retired from teaching in 1959. His first novel written in English, The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, was published in 1941 and his best-known novel, Lolita, brought him worldwide fame. In 1973 he was awarded the American National Medal for Literature. He died in 1977 in Montreux, Switzerland.

Nabokov is one of the great writers of the twentieth century. As Martin Amis has written, The variety, force and richness of Nabokovs perceptions have not even the palest rival in modern fiction. To read him in full flight is to experience stimulation that is at once intellectual, imaginative and aesthetic, the nearest thing to pure sensual pleasure that prose can offer.

PENGUIN CLASSICS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 707 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3008, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, Block D, Rosebank Office Park, 181 Jan Smuts Avenue, Parktown North, Gauteng 2193, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

www.penguin.com

First published by New Directions 1944

Corrected edition published 1961

First published in Penguin Classics 2011

Copyright Article 3C under the Will of Vladimir Nabokov, 1944

All rights reserved

ISBN: 978-1-846-14331-1

PENGUIN MODERN CLASSICS

Nikolai Gogol

The variety, force and richness of Nabokovs perceptions have not even the palest rival in modern fiction the nearest thing to pure sensual pleasure that prose can offer Martin Amis

He did us all an honour by electing to use, and transform, our language Anthony Burgess

The power of the imagination is not apt soon to find another champion of such vigour John Updike

He has moulded and manipulated the language with greater dexterity, wit and invention than any author since Shakespeare Daily Mail

A real magician Paul Bailey

The butterflies of his mind made earthworks of his contemporaries Sunday Times

One of the most original and creative novelists of our time Financial Times

He has mastered all the technical tricks of the novel, and he has invented a few of his own Peter Ackroyd

Besides his gift of translating a subject into sharp-cut visual images, Nabokov has also an extravagant sense of humour, a grasp of the absurd behind the tragic Observer

No, I have not the strength to bear this any longer. God, the things they are doing to me! They pour cold water upon my head! They do not heed me, nor see me, nor listen to me. What have I done to them? Why do they torture me? What do they want of poor me? What can I give them? I have nothing. My strength is gone, I cannot endure all this torture. My head is aflame, and everything spins before my eyes. Save me, someone! Take me away. Give me three steeds, steeds as fast as the whirling wind! Seat yourself, driver, ring out, little harness bell, wing your way up, steeds, and rush me out of this world. On and on, so that nothing be seen of it, nothing. Yonder the sky wheels its clouds; a tiny star glitters afar; a forest sweeps by with its dark trees, and the moon comes in its wake; a silvergrey mist swims below; a musical string twangs in the mist; there is the sea on one hand, there is Italy on the other; and now Russian peasant huts can be discerned. Is that my home looming blue in the distance? Is that my mother sitting there at her window? Mother dear, save your poor son! Shed a tear upon his aching head. See, how they torture him. Press the poor orphan to your heart. There is no place for him in the whole wide world! He is a hunted creature. Mother dear, take pity on your sick little child And by the way, gentlemen, do you know that the Bey of Algiers has a round lump growing right under his nose?

Gogol, Diary of a Madman

1

His Death and His Youth

1

Nikolai Gogol, the strangest prose-poet Russia ever produced, died Thursday morning, a little before eight, on the fourth of March, eighteen fifty-two, in Moscow. He was almost forty-three years old a reasonably ripe age for him, considering the ridiculously short span of life generally allotted to other great Russian writers of his miraculous generation. Absolute bodily exhaustion in result of a private hunger strike (by means of which his morbid melancholy had tried to counter the Devil) culminated in acute anemia of the brain (together, probably, with gastro-enterites through inanition) and the treatment he was subjected to, a vigorous purging and bloodletting, hastened the death of an organism already gravely impaired by the after effects of malaria and malnutrition. The couple of diabolically energetic physicians who insisted on treating him as if he were an average Bedlamite, much to the alarm of their more intelligent but less active colleagues, intended to break the back of their patients insanity before attempting to patch up whatever bodily health he still had left. Some fifteen years before, Pushkin, with a bullet in his entrails, had been given medical assistance good for a constipated child. Second-rate German and French general practitioners still dominated the scene, for the splendid school of great Russian physicians was yet in the making.

The learned doctors crowding around the Malade Imaginaire with their dog-Latin and gigantic belly-pumps cease to be funny when Molire suddenly coughs out his life-blood on the turbulent stage. It is horrible to read of the grotesquely rough handling that Gogols poor limp body underwent when all he asked for was to be left in peace. With as fine a misjudgment of symptoms, as a clear anticipation of the methods of Charcot, Dr Auvers (or Hovert) had his patient plunged into a warm bath where his head was soused with cold water after which he was put to bed with half-a-dozen plump leeches affixed to his nose. He had groaned and cried and weakly struggled while his wretched body (you could feel the spine through the stomach) was carried to the deep wooden bath; he shivered as he lay naked in bed and kept pleading to have the leeches removed: they were dangling from his nose and getting into his mouth (Lift them, keep them away, he pleaded) and he tried to sweep them off so that his hands had to be held by stout Auverts (or Hauverss) hefty assistant.