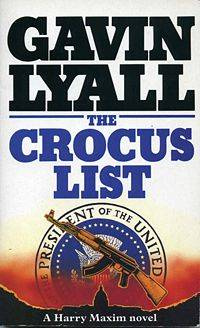

Gavin Lyall

The Crocus List

The Duke was dead. The old Duke, last of a generation of Royal Dukes, the one the press claimed was known as the Steel Duke (though they had made up the name themselves) because he had also been a Field Marshal and a real one. The news, coming late on a September Friday, sent a little ripple through the Army. In the Ministry of Defence it brought a few moments of silence: full generals put down their pens and cups and began recalling chance remarks the Old Man had thrown at them when they were mere subalterns, then winced when they realised they would have to put on Blues and remember how to adjust the stars and sashes of their knighthoods for the memorial service. In outer offices the silence was shorter. Brigadiers and colonels who had never known the Duke, and who would be no part of the service anyway, just said: "Yes, I suppose he _was_ still alive," and went back to writing applications for jobs in personnel management and fund-raising.

In the London barracks of the Household Division and the Cavalry, and among the Duke's own (now much amalgamated) old regiment on station in Osnabrck, the ripple became a wave of mingled apprehension and pride. They-selected echelons of them-would certainly be part of the service, the most visible part, and rehearsal time was short. The British Army prided itself on its parades even more than on its gallant defeats.

And in the military clubs and the Bishop's Bar at the House of Lords, the news brought a welcome change from silence and an ironclad excuse not to go home to their wives. Some, of nearly the Duke's own age, could remember his first wife-a minor European Royal-whom a few claimed to have known "very wellindeed" before her marriage. But she had died in a car crash in the wartime blackout, and been replaced by the daughter of a West Country Earl, herself widowed at Dunkirk. She too had died some time ago, and anybody who remembered her better than well properly kept quiet about it. But most of the reminiscences turned affectionately and regretfully on the Duke himself. He had earned his rank, not just played soldiers like some Royals, and there were those who knewfor a fact that he had been the real brains behind the D-Day landings. After a mission to Moscow he had made a proper study of the Soviet war machine and some said he was the first to realise that the Third World War began the day the Second ended. And his postwar proposals for reforming the regimental system had been remarkable, quite remarkable, although of course the Army had been absolutely right to reject them. The real pity was (they concluded) that the old boy had lived to see the country's defences in such a state, with a timid Prime Minister and coalition Cabinet encouraging the Peace Crusade and seeming to haver over these new Russian proposals for a demilitarised Berlin. Probably what had killed him off, if one did but know it. But he'd had a good innings, and they could show there were still a few who cared by making his memorial service a decent send-off. Provided, of course, that it was held in the proper place and not that bloody great barn over in the City. Still and all, you had to agree that things would never be the same again, and some believed that they hadn't been for some time.

Major Harry Maxim got the news from a chatty guard corporal as he drove out of camp to spend the weekend with his parents, who had looked after his son since his wife's death. It meant nothing to him at all.

After Sunday lunch at Maxim's parents the children went into the back garden and chattered maturely about pop groups and skateboarding while the adults went into the kitchen, where Maxim and his sister Brenda fought. Chris, now aged eleven, and his three cousins had come to accept that this was what happened when they met at Littlehampton, but didn't quite admit to themselves that they went outside to escape the clutching sick feeling of hearing their parents behave like tired brats. The grandparents did most of the actual washing up, since there were never enough tea-towels, so probably Maxim and Brenda were only in there because they were scared, like tired brats, that without referees they might go too far.

"Are you telling us," Brenda asked, "that all those soldiers we've got in Berlin couldn't defend the place anyway?"

"I don't know why you say _all_," Maxim said; "there's only about thirteen thousand Allied troops: roughly a division. And a hundred miles of perimeter, the Wall. One division can't hold that front."

"Then what on earth are they doing there? Just having a good time at the taxpayers' expense?"

"They are there to stop the Russians just walking in. If they go in, they have to go in shooting."

"And just kill off our soldiers and take over anyway."

Maxim shrugged. "And start off World War Three."

"Do we really want to set up things so that the anybody, can start a World War just by accident?"

"They won't walk into West Berlin by accident. But that's what a Standing Army's always been about: to draw a line and say, If you cross that, you've started a real something. So nobody can nibble away with bloodless takeovers. As Hitler did: the Rhineland, Austria, Czechoslovakia."

"And meanwhile, you've got two armies practising to blow each other's countries to bits and getting more and more weapons to do it with. Do you see any end to it?"

"No," Maxim admitted, "but I'm no politician."

"Then why don't you leave it to the politicians?" Brenda asked triumphantly. "Why do you always say they're wrong when they want to talk to the Russians?"

Their mother said from the sink: "Just talking can't do any harm."

"It can if we're doing it unilaterally about Berlin."

"Unilaterally," Brenda said. "Of course, that has to be a dirty word in the Army. I bet you even have to go to the loo multilaterally."

"No, that's strictly a Naval tradition."

"Harry!" A disgusted bark from his father.

"Sorry. But it's sitting down without the Americans and French that does the damage. It splits NATO, it splits the agreement on Berlin. And that's what the Russians want, more than any changes in Berlin."

"Of course, if the Americans don't like it, that's all that matters."

"We have a four-power agreement on Berlin-"

"That was forty years ago. More."

Their father said mildly: "It was the Russians who put up the Berlin Wall. They could take it down without talking to anybody."

"Well, they could, " Brenda said defensively, then burst out: "So why don't we encourage them? Why can't you see how exciting this could be? For the first time in my life-and yours-we're actually taking a step towards peace. Give Berlin back to the Berliners, make it one city, get the tanks and guns out of the streets-can't you see that some people can be as excited about not having tanks and guns as you are abouthaving them? Do you want your Chris to live his whole life waiting for the four-minute warning?"

Their mother said: "I've never seen the point of a warning at all if it's only four minutes. Not that there are any shelters round here, as far as I know."

"Oh, don't worry," Brenda told her. "You'll be safe if you put a paper bag over your head or something daft like that."

"If you're hit by a nuke," Maxim said, "there's nothing you can do. There's nothing you can do if a hand grenade goes off in your pocket, either. But on the fringes of an explosion, any explosion, youcan do something. Anyway, the four-minute warning's the Worst Possible Case. Tactical warning might be that short. But strategic warning"-he was trying to annoy Brenda by using jargon; if he felt his own temper going, he'd try saying 'just a few megadeaths' in a bored tone-"the Red Army's got its mobilisation time down to forty-eight hours, so probably we'll get that much warning. It could be more."

Next page